Imagine a system that learns to recognize objects not by training on millions of labeled images but by browsing the internet and understanding how people naturally describe pictures. This concept is embodied by OpenAI’s CLIP, a foundational shift in teaching machines to interpret visual information.

Traditional computer vision methods rely heavily on vast collections of labeled images to distinguish between categories. For example, discriminating between cats and dogs requires thousands of tagged photos; identifying various car models demands separate extensive datasets. ImageNet, one of the most renowned datasets, enlisted over 25,000 workers to label 14 million images, highlighting the sheer effort required.

This methodology presents three main challenges: the construction of datasets is costly and time-consuming; models tend to specialize narrowly, requiring retraining with new data for different tasks; and models often exploit dataset-specific patterns without genuinely understanding visual concepts. For instance, a model achieving 76% accuracy on ImageNet might perform drastically worse—down to 2.7%—on slightly altered or sketched images, reflecting a lack of true robustness.

CLIP’s approach differs fundamentally by learning from 400 million image-text pairs gathered across the internet. These pairs come from a variety of sources such as Instagram captions, news images, product descriptions, and Wikipedia entries, where people naturally write text that describes or comments on images. This allows CLIP to leverage a vast and diverse training framework.

Rather than predicting predetermined labels, CLIP learns to associate images with corresponding textual descriptions. During training, it evaluates an image against a large batch of text snippets (32,768 at a time) to find the best match. For example, when shown a photo of a golden retriever in a park, only the accurate description—such as “a golden retriever playing fetch in the park”—is correct among thousands of other distractors.

Through repeatedly solving this matching task with diverse internet data, CLIP develops a profound understanding of visual concepts and their linguistic counterparts, associating labels like “dog” or “puppy” with images of furry, four-legged animals, or connecting colors and scenes with terms like “sunset” or “beach.”

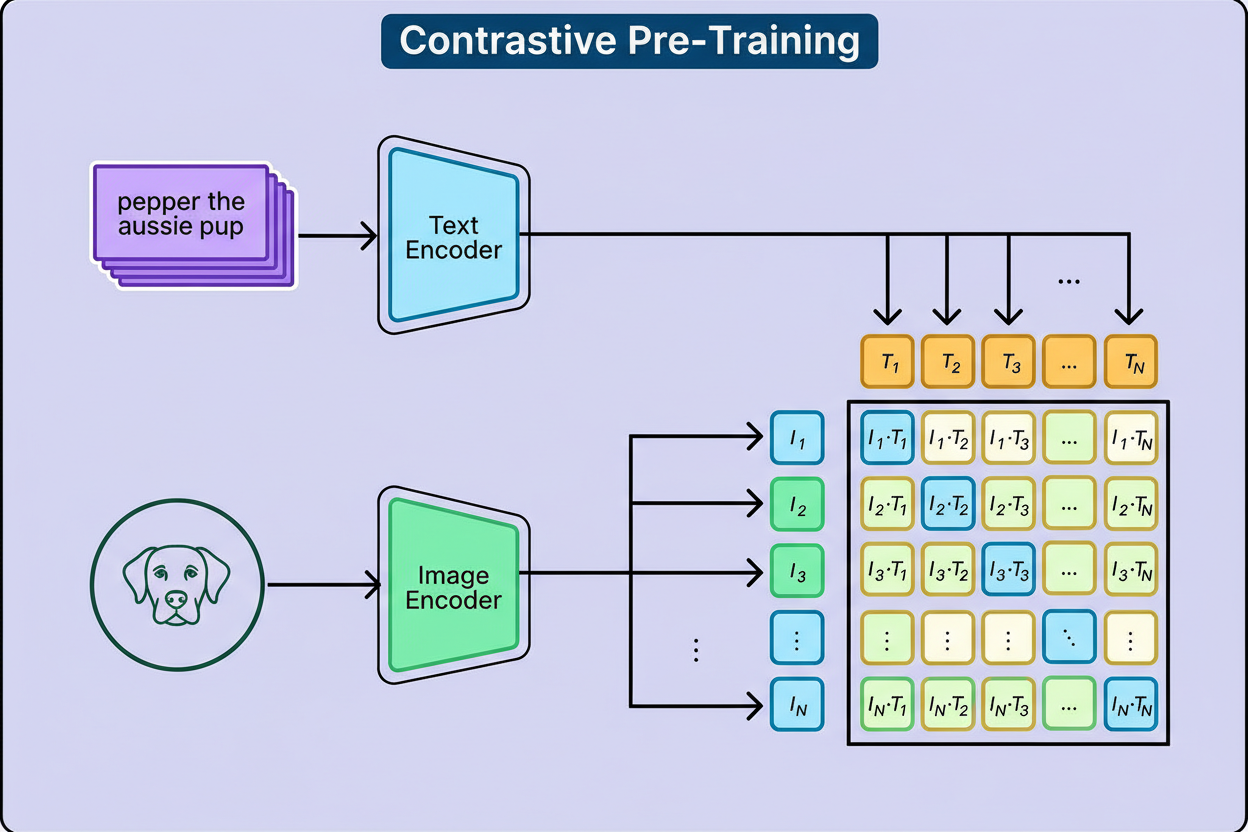

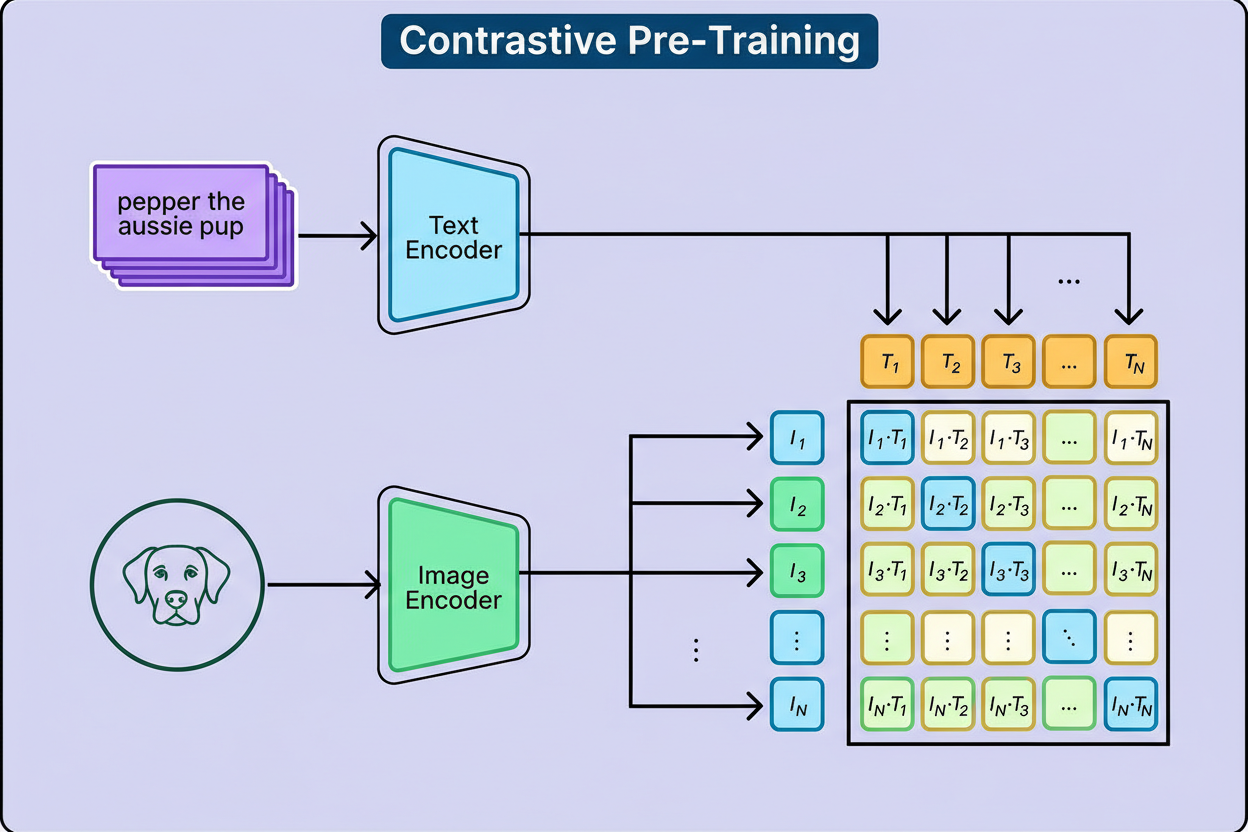

CLIP operates with two neural networks working in tandem: an image encoder and a text encoder. The image encoder transforms raw pixel data into a numerical embedding, while the text encoder converts words and sentences into a comparable vector. Both embeddings exist in the same dimensional space, enabling direct comparison.

Initially, these embeddings appear random and unrelated—for example, the vector for a dog image might be [0.2, -0.7, 0.3, …] while the vector for the word “dog” might be [-0.5, 0.1, 0.9, …]. Training uses a contrastive loss function, mathematically measuring how far embeddings of correct image-text pairs are from each other versus incorrect pairs. Correct pairs are pulled closer in vector space, while incorrect pairs are pushed apart.

Source: OpenAI Research Blog

Source: OpenAI Research Blog

Backpropagation then updates the model weights to minimize this loss, repeating this process millions of times. As a result, the encoders learn to produce embeddings for matching visual and linguistic concepts that are closely aligned, enabling CLIP to “speak the same language” across modalities.

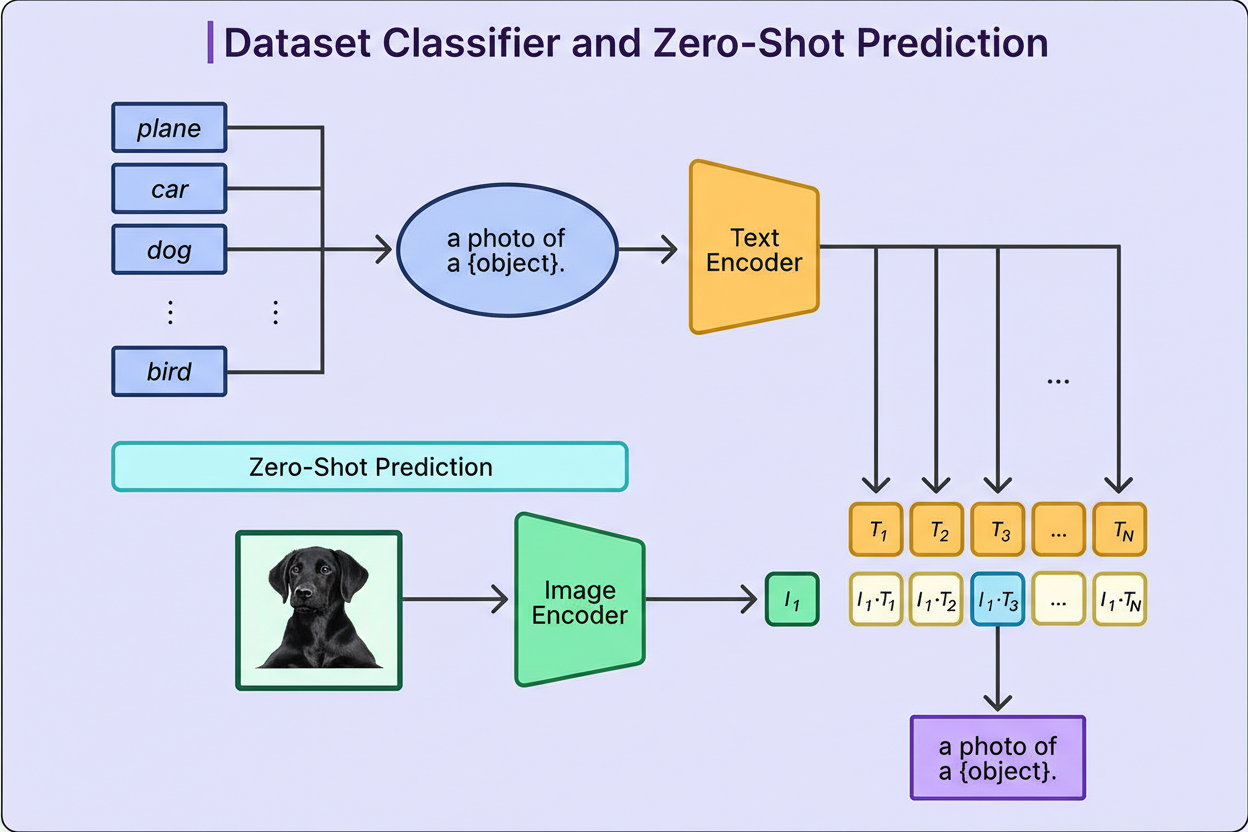

After training, CLIP’s zero-shot functionality allows classification without retraining. For a task such as distinguishing between dogs and cats, the system generates an embedding for the image and compares it with embeddings derived from the text descriptions “a photo of a dog” and “a photo of a cat.” The closest textual embedding determines the classification.

Source: OpenAI Research Blog

Source: OpenAI Research Blog

This method extends to practically any classification problem described in natural language—be it food types (“a photo of pizza,” “a photo of sushi”), satellite imagery (“a satellite photo of forest,” “a satellite photo of city”), or medical imaging (“an X-ray showing pneumonia” versus “an X-ray of healthy lungs”). This flexibility marks a significant advancement over traditional models that required extensive labeled data and retraining.

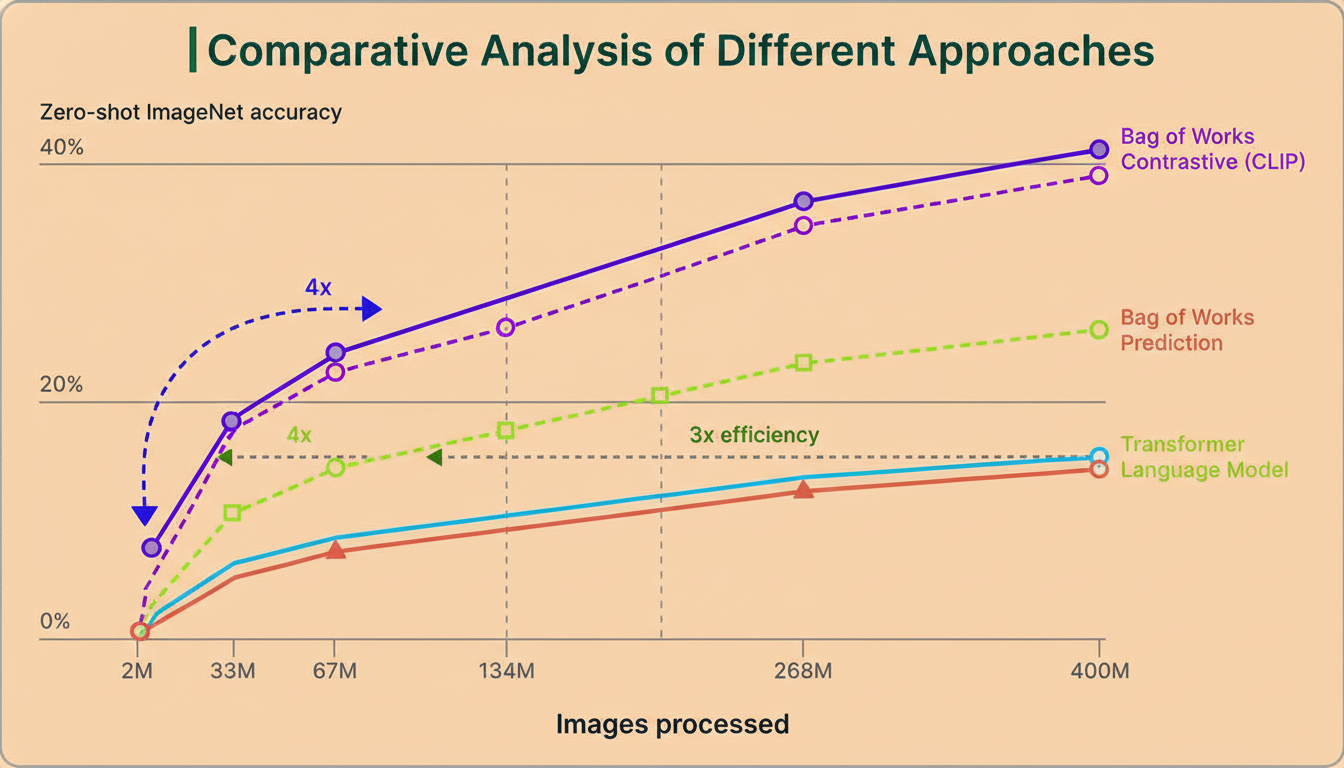

CLIP’s achievements rest on strategic technical decisions by OpenAI. First, contrastive learning was chosen over image caption generation. Generating full captions proved computationally demanding and slow, whereas contrastive learning was 4 to 10 times more efficient while achieving strong zero-shot results.

Second, the adoption of Vision Transformers for the image encoder leveraged transformer architecture’s success in natural language processing. Treating image patches like words yielded a 3x efficiency improvement compared to convolutional neural networks such as ResNet.

Source: OpenAI Research Blog

Source: OpenAI Research Blog

These innovations allowed training on 256 GPUs over two weeks, comparable to other large vision models, without prohibitive computational costs.

OpenAI evaluated CLIP on more than 30 datasets encompassing fine-grained classification, OCR, action recognition, geographic localization, and satellite imagery. CLIP matched ResNet-50’s 76.2% accuracy on ImageNet and outperformed the leading public ImageNet model on 20 of 26 transfer learning tasks. It excelled under stress tests where conventional models failed, achieving 60.2% on ImageNet Sketch (versus ResNet’s 25.2%) and 77.1% on adversarial examples (compared to ResNet’s 2.7%).

However, certain challenges remain. Tasks demanding precise spatial reasoning or fine-grained distinctions, such as differentiating similar car or aircraft models, prove difficult. On the MNIST handwritten digits dataset, CLIP reached 88% accuracy, below human-level performance of 99.75%. Additionally, the model’s output can vary significantly based on phrasing of text prompts, necessitating prompt engineering. It also inherits biases from its internet-sourced training data that affect behavior unpredictably.

Despite these limitations, CLIP demonstrates that the principles behind natural language breakthroughs can extend to computer vision. Mirroring GPT’s learning from large-scale internet text, CLIP’s training on extensive internet image-text pairs enables versatile visual recognition.

Since its release, CLIP has become widely adopted in AI, fueling technologies like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E for text-to-image generation and serving numerous applications such as image search, content moderation, and recommendation systems.