Interacting with a large language model by writing a few lines of prompts often yields sonnets, debugging suggestions, or complex analyses almost instantly. This software-centric perspective might overshadow a fundamental reality: artificial intelligence extends beyond software; it encompasses a physics problem concerning electron movement through silicon and the challenge of transferring immense data volumes between memory and compute units.

Nevertheless, sophisticated AI tools, such as LLMs, cannot be constructed solely with CPUs. The CPU’s design prioritizes logic, branching decisions, and serial execution. In contrast, deep learning mandates linear algebra, extensive parallelism, and probabilistic operations.

This article explores the architectural contributions of GPUs and TPUs in constructing modern LLMs.

At its core, every neural network executes one fundamental operation billions of times: matrix multiplication.

When an LLM receives a question, the input words are converted into numbers that traverse hundreds of billions of multiply-add operations. A single forward pass through a 70-billion-parameter model necessitates over 140 trillion floating-point operations.

The underlying mathematical structure is direct. Each layer computes Y = W * X + B, where X denotes input data, W holds learned parameters, B is a bias vector, and Y signifies the output. Scaling this to billions of parameters involves trillions of simple multiplications and additions.

The distinctiveness of this workload stems from its dependence on parallel computation. Each multiplication within a matrix operation operates entirely independently. Calculating row 1 multiplied by column 1 does not necessitate waiting for row 2 multiplied by column 2. The work can be distributed across thousands of processors with no communication overhead during computation.

The Transformer architecture further enhances this parallelism. Its self-attention mechanism computes relationship scores between every token and every other token. For a 4,096-token context window, this generates over 16 million attention pairs. Each transformer layer executes several significant matrix multiplications, and a 70-billion-parameter model can perform millions of these operations per forward pass.

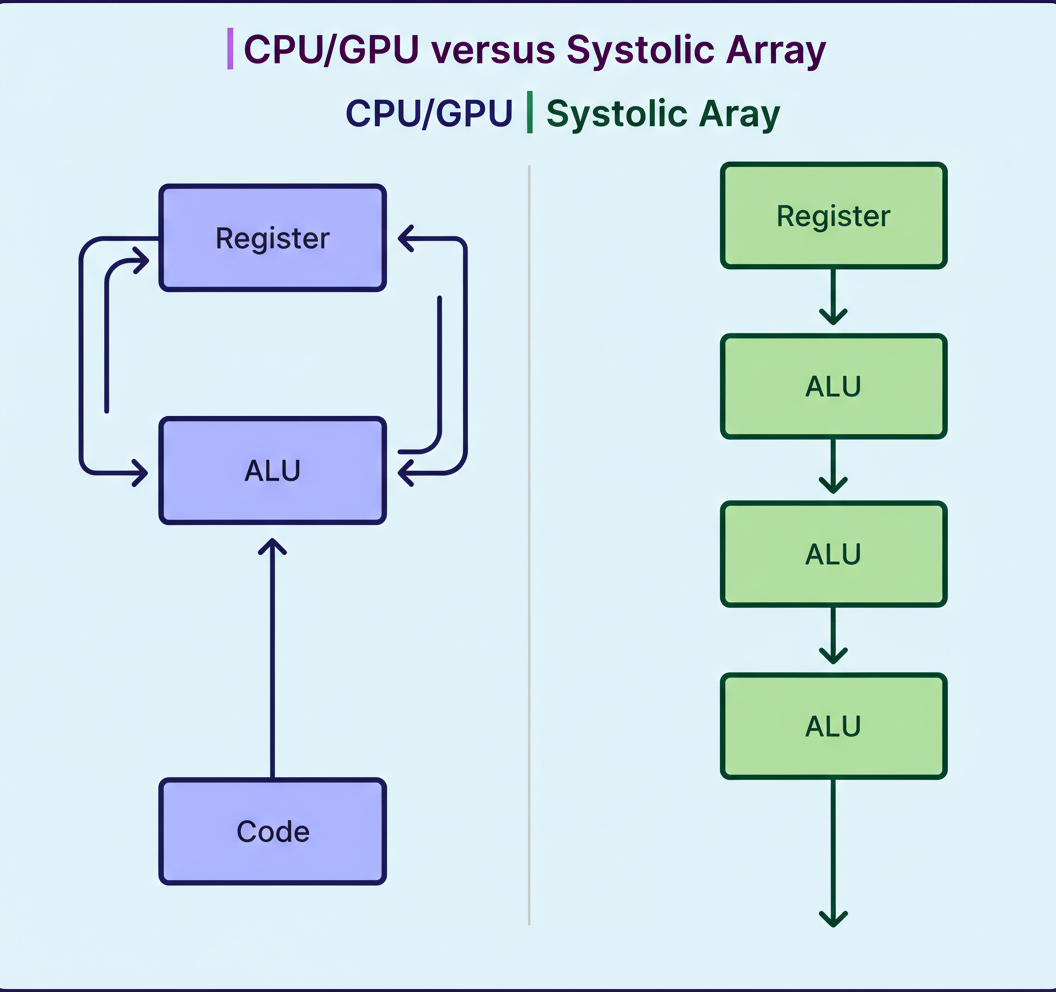

CPUs demonstrate proficiency in tasks demanding complex logic and branching decisions. Modern CPUs incorporate intricate mechanisms tailored for unpredictable code paths; however, neural networks do not necessitate these functionalities.

Branch prediction machinery attains 93-97% accuracy in predicting conditional statement outcomes, utilizing substantial silicon area. Conversely, neural networks exhibit minimal branching, executing identical operations billions of times with predictable patterns.

Out-of-order execution reorders instructions to maintain processor activity while awaiting data. Matrix multiplication features perfectly predictable access patterns that derive no benefit from this intricacy. Extensive cache hierarchies (L1, L2, L3) mitigate memory latency for random access, yet neural network data flows sequentially through memory.

Consequently, only a small fraction of a CPU die is allocated to arithmetic. The majority of the transistor budget is devoted to control units overseeing out-of-order execution, branch prediction, and cache coherency. During LLM operation, these billions of transistors remain inactive, consuming power and occupying space that could otherwise be utilized for arithmetic units.

Beyond computational inefficiency, CPUs encounter an even more fundamental constraint: the Memory Wall. This phenomenon characterizes the growing disparity between processor speed and memory access speed.

Large language models are inherently massive. A 70-billion parameter model, stored in 16-bit precision, occupies approximately 140 gigabytes of memory. To produce a single token, the processor must retrieve every single parameter from memory to execute the requisite matrix multiplications.

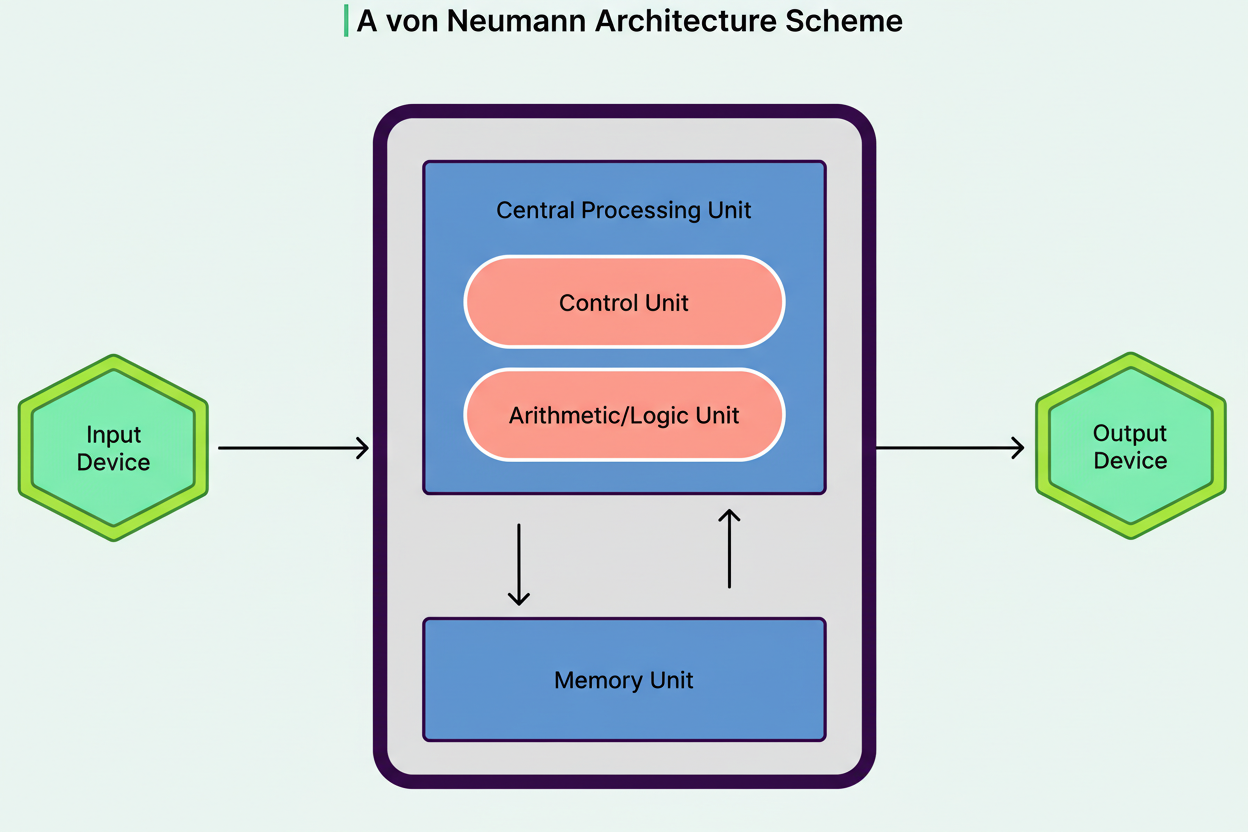

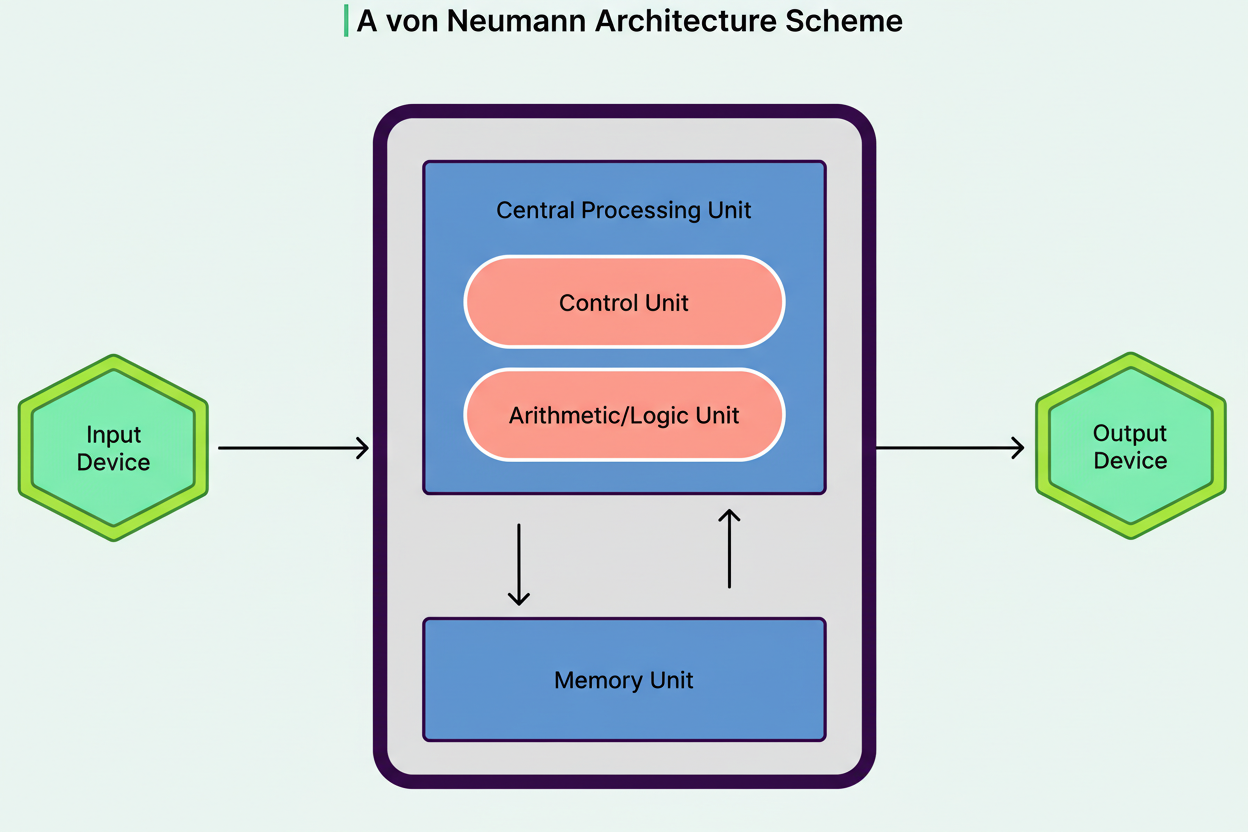

Conventional computers adhere to the Von Neumann architecture, where a processor and memory communicate via a shared bus. For any calculation, the CPU must fetch an instruction, retrieve data from memory, execute the operation, and write results back. This continuous data transfer between the processor and memory establishes what computer scientists term the Von Neumann bottleneck.

Neither an increase in core count nor clock speed can resolve this issue. The bottleneck resides not in arithmetic operations but in the rate at which data can be supplied to the processor. Therefore, memory bandwidth, rather than raw compute power, frequently dictates LLM performance.

The Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) was initially conceived for rendering video games. The mathematical demands inherent in rendering millions of pixels bear a striking resemblance to deep learning, as both necessitate extensive parallelism and high-throughput floating-point arithmetic.

NVIDIA’s GPU architecture employs SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads). Its fundamental unit is a group of 32 threads, termed a warp. All threads within a warp share a single instruction decoder, executing the same instruction concurrently. This shared control unit significantly conserves silicon area, which is instead populated with thousands of arithmetic units.

While contemporary CPUs feature 16 to 64 complex cores, the NVIDIA H100 incorporates nearly 17,000 simpler cores. These operate at lower clock speeds (1-2 GHz compared to 3-6 GHz), yet immense parallelism compensates for slower individual operations.

Standard GPU cores execute operations on single numbers, one at a time per thread. Recognizing the dominance of matrix operations in AI workloads, NVIDIA introduced Tensor Cores, beginning with their Volta architecture. A Tensor Core is a specialized hardware unit that completes an entire matrix multiply-accumulate operation within a single clock cycle.

While a standard core performs one floating-point operation per cycle, a Tensor Core executes a 4×4 matrix multiplication involving 64 individual operations (16 multiplies and 16 additions in the multiply step, plus 16 accumulations) instantaneously. This represents a 64-fold improvement in throughput for matrix operations.

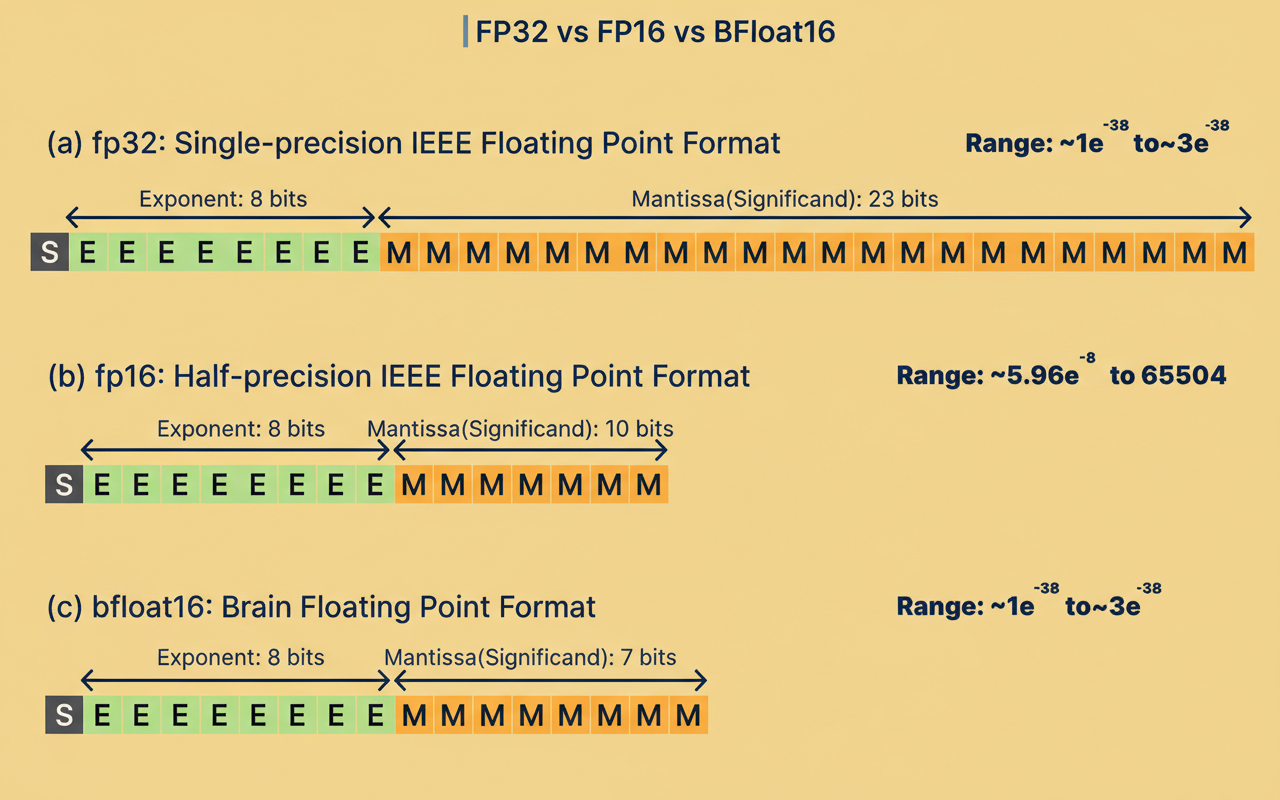

Tensor Cores also support mixed-precision arithmetic, a critical aspect for practical AI deployment. They can accept inputs in lower precision formats like FP16 or BF16 (utilizing half the memory of FP32) while accumulating results in higher precision FP32 to maintain numerical accuracy. This combination boosts throughput and diminishes memory requirements without sacrificing the precision essential for stable model training and accurate inference.

To supply these thousands of compute units, GPUs leverage High Bandwidth Memory (HBM). Unlike DDR memory, which resides on separate modules plugged into the motherboard, HBM comprises DRAM dies stacked vertically using through-silicon vias (microscopic vertical wires). These stacks are positioned on a silicon interposer directly adjacent to the GPU die, minimizing the physical distance data must traverse.

Such an architecture enables GPUs to achieve memory bandwidths exceeding 3,350 GB/s on the H100, surpassing CPUs by more than 20 times. With this bandwidth, an H100 can load a 140 GB model in approximately 0.04 seconds, facilitating token generation speeds of 20 or more tokens per second. This speed makes the difference between a fragmented, frustrating interaction and a fluid conversational pace.

The synergy of massive parallel computing and extreme memory bandwidth positions GPUs as the predominant platform for AI workloads.

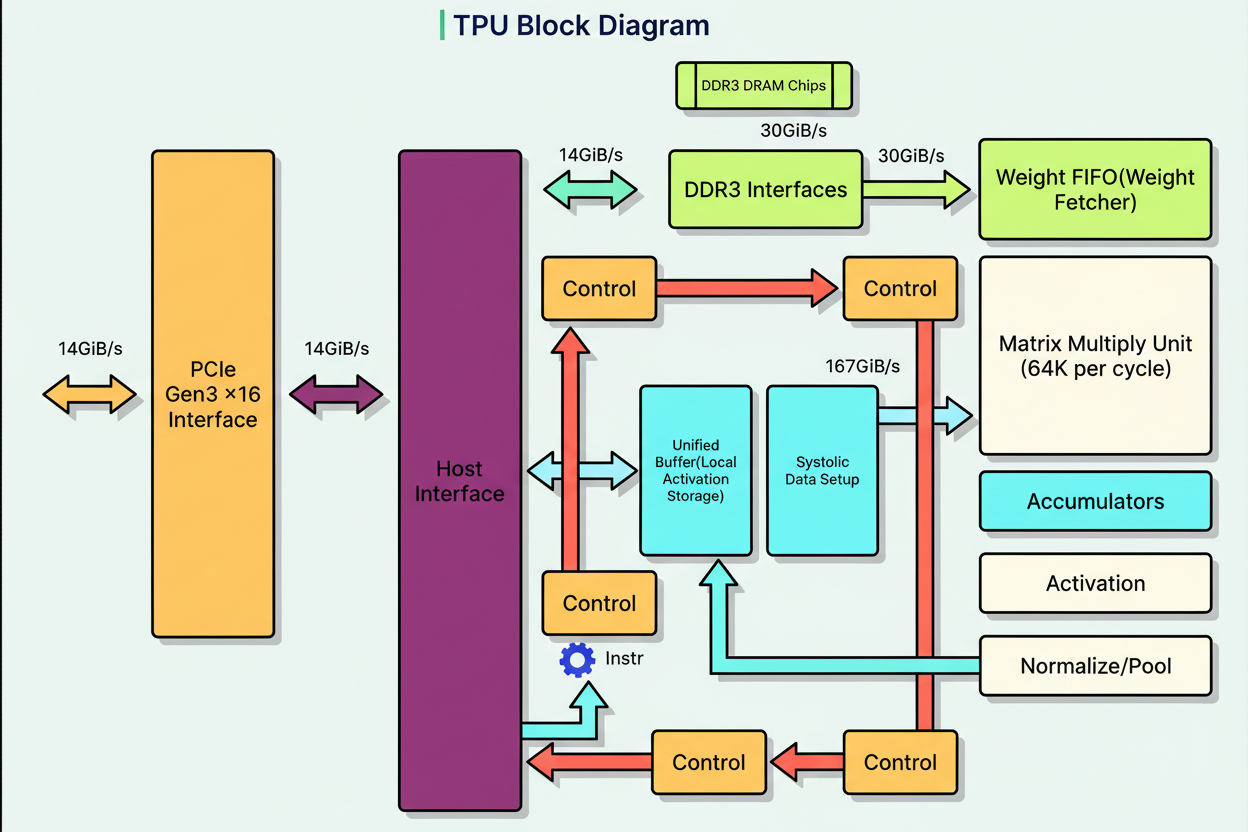

In 2013, Google determined that if every user engaged in voice search for merely three minutes daily, their datacenter capacity, reliant on CPUs, would need to double. This realization prompted the development of the Tensor Processing Unit (TPU).

The diagram below illustrates:

The distinctive characteristic of the TPU is its systolic array, a grid of interconnected arithmetic units (256 by 256, totaling 65,536 processors). Weights are loaded into this array and remain constant, while input data flows horizontally. Each unit multiplies its stored weight by the incoming data, adds to a running sum moving vertically, and transmits both values to its adjacent neighbor.

This architecture ensures that intermediate values never access main memory. Reading from DRAM consumes approximately 200 times more energy than a multiplication operation. By sustaining the flow of results between neighboring processors, systolic arrays effectively eliminate most memory access overhead, achieving 30 to 80 times superior performance per watt compared to CPUs.

Google’s TPU design omits caches, branch prediction, out-of-order execution, and speculative prefetching. While this extreme specialization precludes TPUs from executing general code, the efficiency enhancements for matrix operations are considerable. Google furthermore introduced bfloat16, a format that allocates 8 bits for the exponent (matching the FP32 range) and 7 bits for the mantissa. Neural networks tolerate lower precision but necessitate a broad range, rendering bfloat16 an optimal format.

An understanding of hardware distinctions carries direct practical implications.

Training and inference processes possess fundamentally distinct requirements.

Training involves storing parameters, gradients, and optimizer states. As a reference, total memory demands can reach 16 to 20 times the parameter count. For instance, training LLaMA 3.1, with its 405 billion parameters, necessitated 16,000 H100 GPUs, each equipped with 80GB.

Inference proves more accommodating; it bypasses backpropagation, thereby requiring fewer operations. This characteristic explains why 7-billion parameter models can be executed on consumer GPUs, which are typically insufficient for training.

Batch processing significantly impacts efficiency. GPUs attain peak performance by concurrently processing multiple inputs. Each additional input helps amortize the cost associated with loading weights. Conversely, single-request inference frequently underutilizes parallel hardware.

The evolution from CPU to GPU and TPU signifies a fundamental change in computing philosophy. The CPU epitomizes an era of logic and sequential operations, optimized for low latency. GPUs and TPUs, however, represent an era of data transformation through probabilistic operations. These are specialized engines of linear algebra that achieve results through extensive parallel arithmetic.