Before 2019, Google developed a system designed to manage permissions for billions of users, ensuring both correctness and high performance.

When a Google Doc is shared or a YouTube video is made private, a sophisticated system operates discreetly to guarantee that only authorized individuals can access the content. This system is Zanzibar, Google’s global authorization infrastructure, which processes over 10 million permission checks per second across diverse services such as Drive, YouTube, Photos, Calendar, and Maps.

This article examines the high-level architecture of Zanzibar, offering valuable insights for constructing large-scale systems, especially concerning the intricacies of distributed authorization. The challenges in achieving massive scale, similar to those faced during Black Friday Cyber Monday scale testing or Shopify BFCM readiness, highlight the importance of robust authorization.

The diagram below illustrates the high-level architecture of Zanzibar.

This article draws upon publicly shared details from the Google Engineering Team. Any inaccuracies should be brought to attention in the comments.

Authorization addresses a fundamental question: Can a specific user access a particular resource? For smaller applications with limited user bases, verifying permissions presents a straightforward task. This often involves maintaining a list of authorized users for each document and confirming the requesting user’s presence on that list.

The complexity escalates significantly at Google’s operational scale. Zanzibar, for instance, manages over two trillion permission records, distributed and served from dozens of data centers globally. A common user interaction can initiate tens or even hundreds of permission checks. When a user searches for an artifact in Google Drive, the system is mandated to verify access to each result prior to its display. Any latency in these verification processes directly diminishes user experience. This requirement for high-speed authorization is crucial for effective capacity planning in global systems.

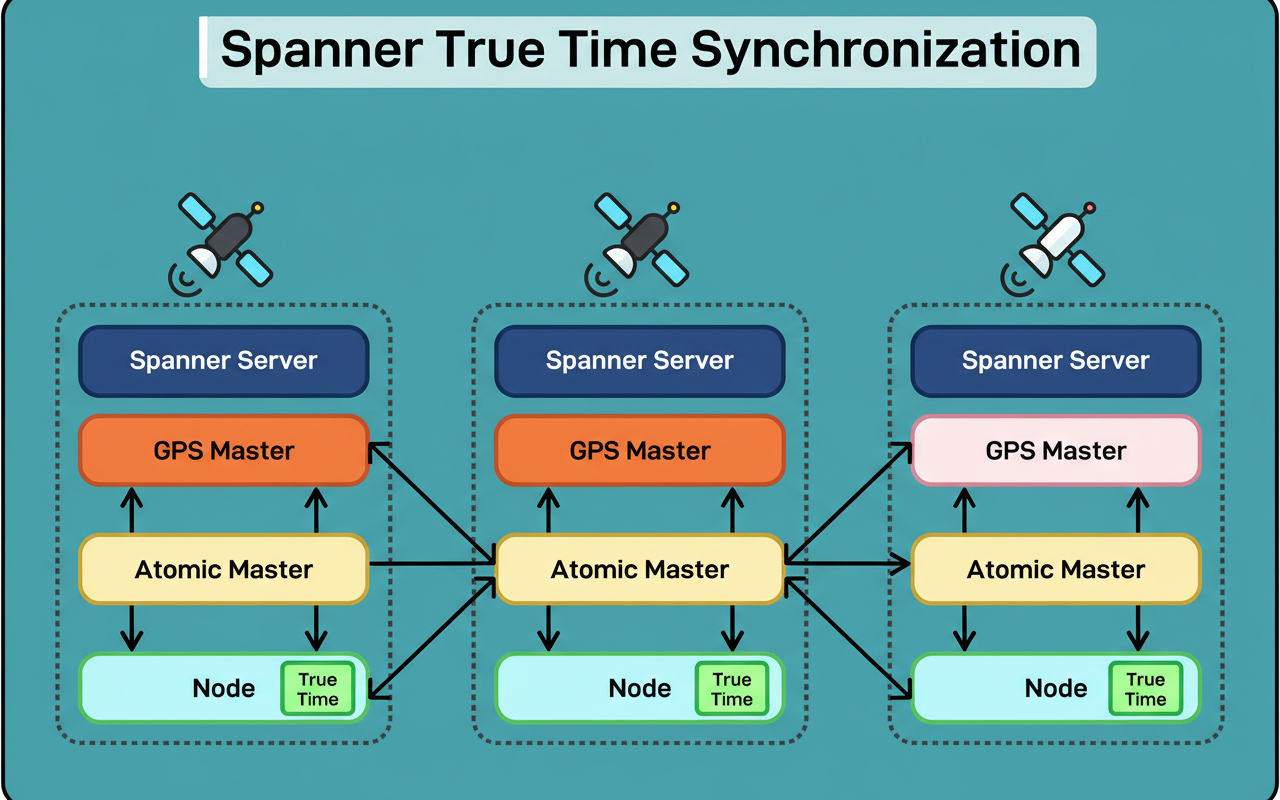

Beyond the mere challenge of scale, authorization systems also contend with a critical correctness issue, which Google refers to as the “new enemy” problem. Consider a scenario where an individual is removed from a document’s access list, and subsequently, new content is added to that document. If the system operates with stale permission data, the recently removed individual might still gain visibility into the new content. This discrepancy arises when the system fails to accurately track the chronological order of modifications.

Zanzibar addresses these multifaceted challenges through three pivotal architectural decisions:

A flexible data model founded on tuples.

A consistency protocol that strictly adheres to causality.

A serving layer meticulously optimized for prevalent access patterns.

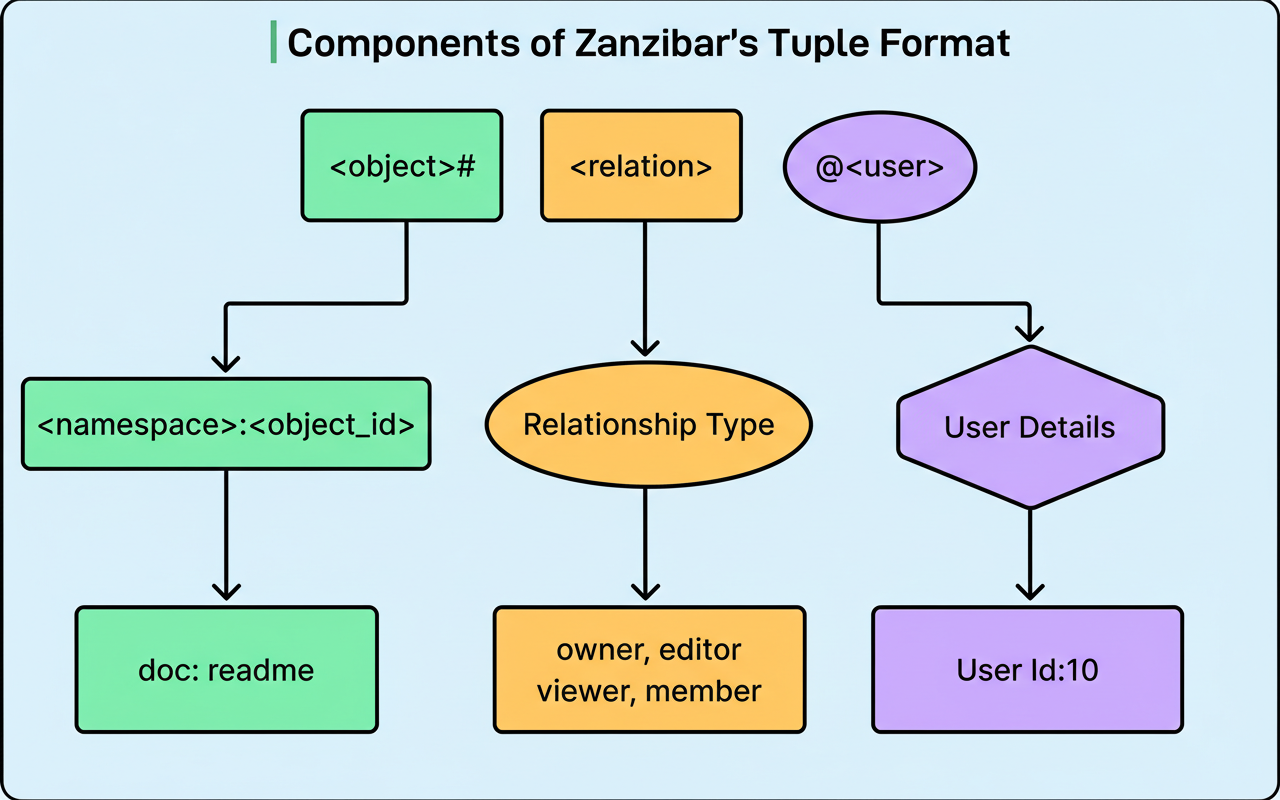

Zanzibar standardizes all permissions as relation tuples, which are straightforward declarations outlining relationships between objects and users. A tuple adheres to the format: object, relation, user. For instance, “document 123, viewer, Alice” signifies that Alice possesses viewing privileges for document 123.

The diagram below illustrates this concept:

This tuple-centric methodology diverges from conventional access control lists, which directly associate permissions with objects. Tuples possess the capability to reference other tuples. Rather than meticulously enumerating each group member on a document, a single tuple can assert that “members of the Engineering group can view this document.” Consequently, alterations to the Engineering group’s membership are automatically mirrored in the document’s permissions.

The system structures tuples into namespaces, serving as containers for objects of an identical type. Google Drive, for example, might employ distinct namespaces for documents and folders, while YouTube utilizes namespaces for videos and channels. Each defined namespace dictates the permissible relations and their interdependencies.

Zanzibar’s clients are empowered to utilize a configuration language to articulate rules governing the composition of relations. For example, a configuration might stipulate that all editors are implicitly viewers, but not all viewers are necessarily editors.

The code snippet below demonstrates the configuration language approach for defining relations.

Source: Zanzibar Research Paper (URL: https://research.google/pubs/zanzibar-googles-consistent-global-authorization-system/)

These directives, termed userset rewrites, enable the system to infer intricate permissions from fundamental stored tuples. For instance, consider a document residing within a folder. If the folder has designated viewers, and the intent is for these viewers to automatically access all documents within that folder, a rule can be formulated. Instead of replicating the viewer list for every single document, a rule specifies that to ascertain who can view a document, the system should consult its parent folder and incorporate that folder’s viewers. This method facilitates permission inheritance while circumventing data duplication, crucial for efficient Google Cloud multi-region deployments.

The configuration language offers support for set operations, including union, intersection, and exclusion. A YouTube video, for example, might designate its viewers to encompass direct viewers, in addition to viewers of its parent channel, and anyone authorized to edit the video. This inherent flexibility empowers various Google services to define their unique authorization policies utilizing the identical underlying system.

The “new enemy” problem underscores the inherent difficulty of distributed authorization. When access is revoked and content is subsequently modified, the coordination of two distinct systems becomes imperative:

Zanzibar, responsible for permissions.

The application, managing content.

Zanzibar resolves this challenge by employing tokens known as zookies. When an application commits new content, it initiates an authorization request to Zanzibar. Upon successful authorization, Zanzibar provides a zookie, which encapsulates the current timestamp, and this zookie is then stored by the application alongside the content.

Subsequently, when an individual attempts to view that content, the application transmits both the viewer’s identity and the previously stored zookie to Zanzibar. This instructs Zanzibar to perform a permission verification using data that is at least as current as the specified timestamp. As the timestamp originated subsequent to any permission alterations, Zanzibar accurately reflects those changes during the check.

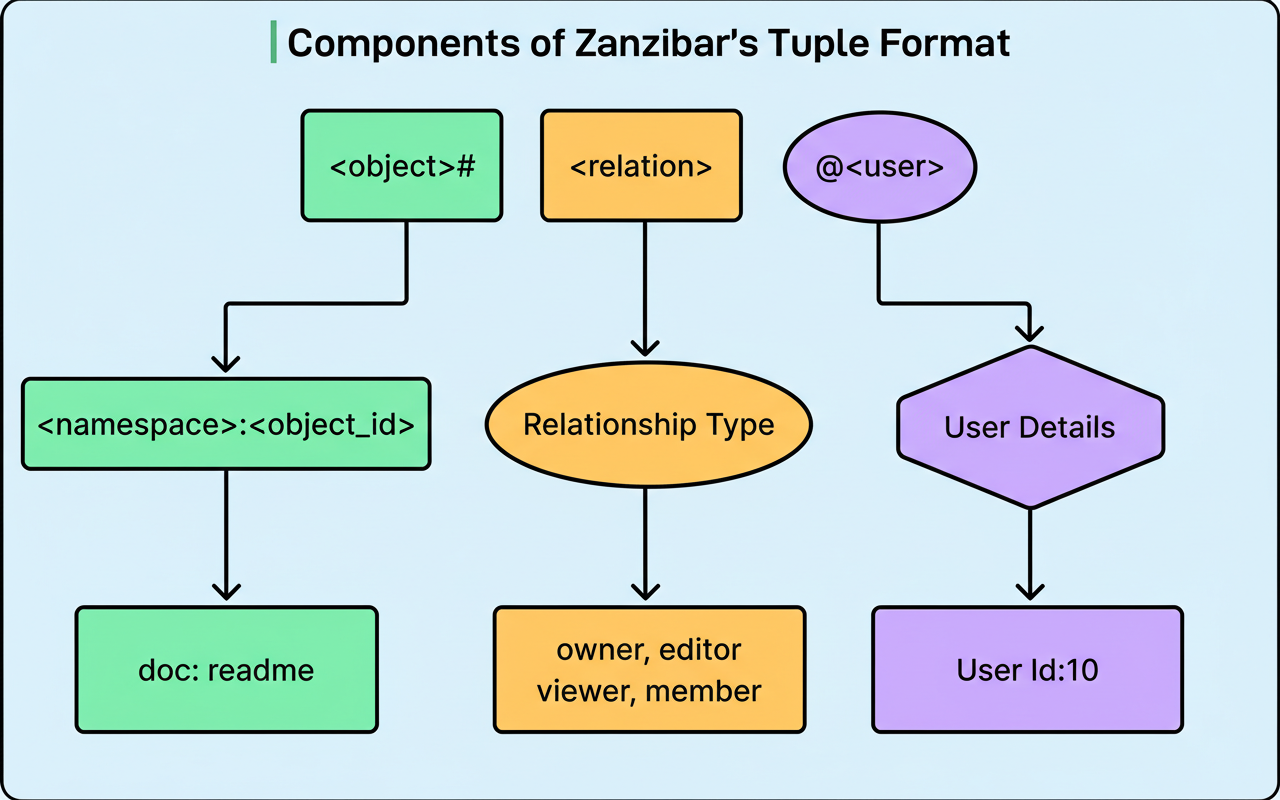

This protocol is effective due to Zanzibar’s reliance on Google Spanner, a globally distributed database that guarantees external consistency.

Should event A precede event B in real-world time, their respective timestamps accurately mirror that sequence across all global data centers, facilitated by Spanner’s TrueTime technology.

The zookie protocol possesses a crucial characteristic: it designates the minimum necessary data freshness, rather than a precise timestamp. Zanzibar retains the flexibility to employ any timestamp that is equivalent to or fresher than the stipulated requirement, thereby enabling significant performance optimizations.

Zanzibar operates across more than 10,000 servers, distributed among dozens of clusters globally. Each cluster comprises hundreds of servers collaborating to fulfill authorization requests. The system meticulously replicates all permission data to over 30 geographic locations, thereby ensuring that verification processes can be executed in close proximity to end-users. This extensive Google Cloud multi-region deployment underpins its global reach and resilience, efficiently handling edge network requests per minute.

Upon the arrival of a check request, it is routed to any server within the closest cluster, with that server assuming the role of coordinator for the specific request. Depending on the permission configuration, the coordinator may be required to communicate with other servers to assess various components of the check. These servers, in turn, might recursively engage with further servers, especially when verifying membership within deeply nested groups.

For example, determining if Alice possesses the authority to view a document could necessitate verifying her status as an editor (which inherently confers viewer access), confirming whether her group affiliations bestow access, and ascertaining if the document’s parent folder grants access. Each of these individual checks can be executed concurrently on separate servers, with their respective outcomes subsequently aggregated.

The distributed characteristic of this processing inherently risks the creation of potential hotspots. Widely accessed content typically generates numerous concurrent permission checks, all directed towards the identical underlying data. Zanzibar utilizes several strategies to alleviate these hotspots:

Firstly, the system upholds a distributed cache spanning all servers within a cluster. Through the application of consistent hashing, interconnected checks are directed to the same server, enabling that server to cache results and subsequently serve identical checks directly from its memory. The cache keys incorporate timestamps, facilitating the sharing of cached results among checks occurring at the same temporal point.

Secondly, Zanzibar leverages a lock table to deduplicate identical concurrent requests. When numerous requests for the same verification arrive simultaneously, only a single request is actually executed. The remaining requests await the outcome, after which all receive the identical response. This mechanism effectively thwarts flash crowds from incapacitating the system before the cache achieves optimal performance.

Thirdly, concerning exceptionally frequently accessed items, Zanzibar performs a complete read of the entire permission set in a single operation, rather than verifying individual users. While this approach consumes greater bandwidth during the initial read, subsequent checks for any user can be efficiently resolved from the comprehensively cached set.

The system further exhibits intelligent decision-making regarding the evaluation location of checks. The inherent flexibility of zookies, as previously discussed, permits Zanzibar to approximate evaluation timestamps to broader intervals, such as one-second or ten-second periods. This quantization implies that numerous checks are evaluated at the same timestamp, enabling the sharing of cache entries and consequently enhancing hit rates significantly. This is a crucial aspect of chaos engineering to ensure system stability.

Certain scenarios present deeply nested group hierarchies or groups encompassing thousands of subgroups. Ascertaining membership through the recursive traversal of relationships proves prohibitively slow when these structures attain significant scale.

Zanzibar incorporates a component named Leopard, which sustains a denormalized index by precomputing transitive group membership. Rather than tracing sequential relationships such as “Alice is in Backend, Backend is in Engineering,” Leopard directly stores mappings from users to every group they are affiliated with.

Leopard employs two distinct categories of sets: one delineates users in relation to their direct parent groups, while the other maps groups to all their descendant groups. Consequently, verifying Alice’s affiliation with the Engineering group transforms into a set intersection operation, completing within milliseconds.

Leopard preserves the consistency of its denormalized index via a two-tiered methodology. An offline process constructs a comprehensive index from snapshots at regular intervals. Concurrently, an incremental layer monitors for changes and applies them atop the existing snapshot. Queries merge both layers to ensure consistent results.

Zanzibar’s operational performance demonstrates significant optimization for typical usage scenarios. Approximately 99% of permission checks leverage moderately stale data, served exclusively from local replicas. These checks exhibit a median latency of 3 milliseconds, achieving the 95th percentile at 9 milliseconds. The residual 1% necessitating fresher data experience a 95th percentile latency of approximately 60 milliseconds, primarily attributable to cross-region communication.

Write operations are intentionally designed to be slower, manifesting a median latency of 127 milliseconds, which reflects the overhead of distributed consensus. Nonetheless, write operations constitute merely 0.25% of the overall system operations.

Zanzibar utilizes request hedging as a strategy to diminish tail latency. Upon dispatching a request to one replica and failing to receive a response within a predefined threshold, the system dispatches an identical request to an alternative replica, ultimately using the response from whichever replica responds first. Each server meticulously monitors latency distributions and autonomously calibrates parameters such as default staleness and hedging thresholds, critical for maintaining high edge network requests per minute.

The operation of a shared authorization service, catering to hundreds of client applications, mandates rigorous isolation among clients. The behavior of a malfunctioning or unexpectedly popular feature within one application must not adversely impact others.

Zanzibar implements isolation across various architectural layers. Each client is allocated CPU quotas, quantified in generic compute units. Should a client surpass its allocated quota during phases of resource contention, its requests are subjected to throttling, while other clients remain unimpeded. The system additionally imposes limitations on the volume of concurrent requests per client and the concurrent database reads per client.

The lock tables, instrumental for deduplication, incorporate the client identity within their keys. This design guarantees that if a single client generates a hotspot that saturates its lock table, the requests from other clients can continue to be processed independently.

These isolation mechanisms have demonstrated their criticality in a production environment. When clients introduce new features or encounter unforeseen usage patterns, any arising issues remain effectively compartmentalized. Across more than three years of operation, Zanzibar has sustained an impressive 99.999% availability, translating to less than two minutes of downtime per quarter. This level of resilience is paramount for robust Shopify BFCM readiness and preventing system failures during peak loads.

Google’s Zanzibar embodies five years of production evolution, currently serving hundreds of applications and billions of users. The system unequivocally demonstrates that authorization at an immense scale necessitates more than merely high-speed databases. It demands meticulous consideration for consistent semantics, intelligent caching and optimization strategies, and robust isolation protocols among clients.

Zanzibar’s architectural design offers profound insights applicable even beyond Google’s operational magnitude. The tuple-based data model establishes a clear abstraction that unifies access control lists and group membership. By decoupling policy configuration from data storage, the system facilitates easier evolution of authorization logic without the need for extensive data migration.

The consistency model employed by Zanzibar illustrates that robust guarantees are attainable within globally distributed systems, provided careful protocol design. The zookie methodology effectively balances correctness with performance, affording the system controlled flexibility.

Crucially, Zanzibar exemplifies an optimization philosophy centered on observed behavior, rather than solely theoretical worst-case scenarios. The system excels at handling the common scenario of stale reads, while adequately supporting the less frequent requirement for fresh reads. The sophisticated caching strategies underscore how to surmount the limitations of normalized storage while rigorously preserving correctness.

For engineers building authorization systems, Zanzibar provides a comprehensive reference architecture. Even at smaller scales, the principles of tuple-based modeling, explicit consistency guarantees, and optimization through measurement remain valuable. This holistic approach, including elements of chaos engineering, is essential for designing resilient authorization solutions.

References:

Zanzibar: Google’s Consistent, Global Authorization System

Zanzibar: Google’s Consistent, Global Authorization System (URL: https://research.google/pubs/zanzibar-googles-consistent-global-authorization-system/)

Authentication vs Authorization: What’s the difference?

Authentication vs Authorization: What’s the difference? (URL: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/authentication-vs-authorization)

Spanner: Google’s Globally Distributed Database

Spanner: Google’s Globally Distributed Database (URL: https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//archive/spanner-osdi2012.pdf)