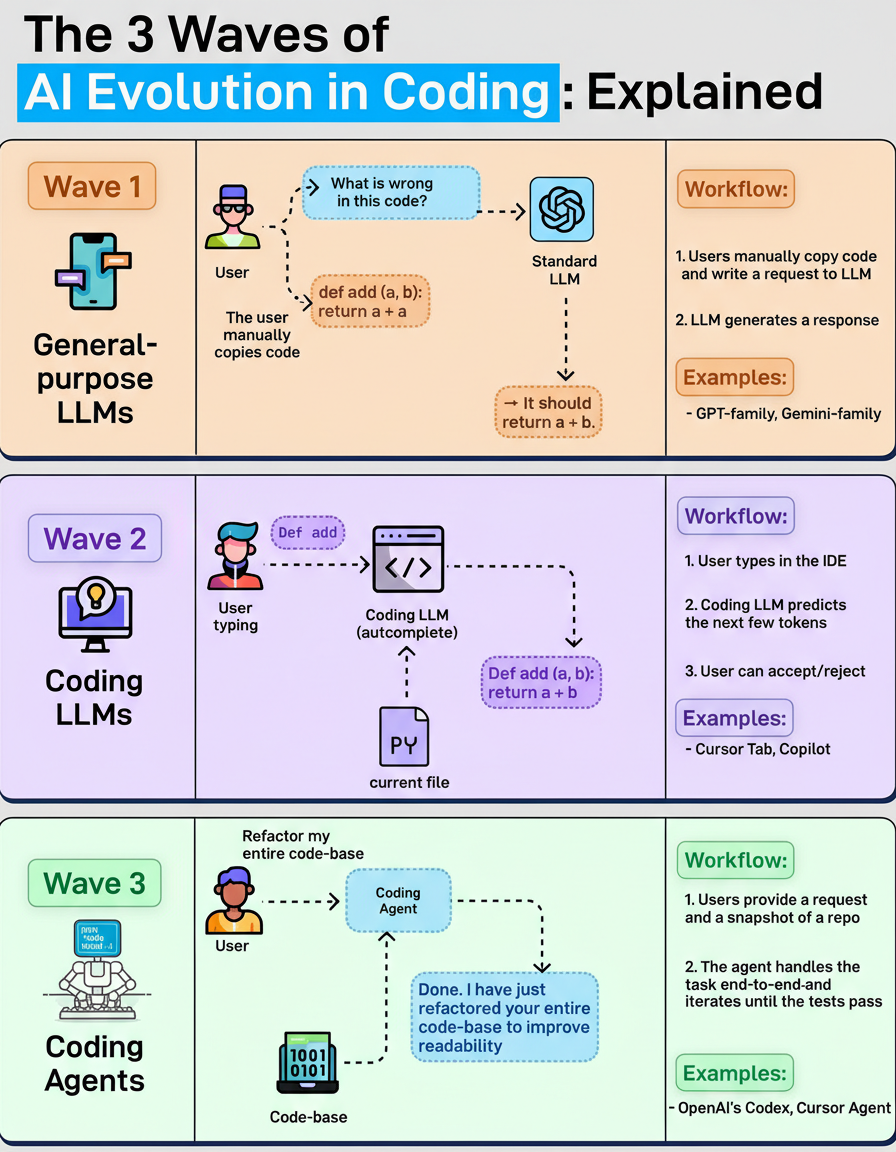

Artificial intelligence has profoundly transformed the methodologies employed by software engineers. This significant paradigm shift can be delineated into three distinct evolutionary phases.

Early adoption involved utilizing general-purpose large language models, commonly perceived as chat assistants. Engineers would input code snippets into platforms such as ChatGPT, solicit error diagnostics, and then manually implement the suggested corrections. While this approach offered accelerated development, the overall workflow remained characterized by its manual and time-consuming nature.

The advent of specialized coding large language models, manifested as autocomplete tools like Copilot and Cursor Tab, integrated AI directly into the development environment. These models offer predictive token suggestions as developers type, allowing for acceptance or rejection. This significantly enhances typing speed but demonstrates limitations when addressing repository-wide tasks.

A more advanced stage involves coding agents, which are designed to manage development tasks comprehensively from inception to completion. A developer might issue a command such as “refactor the code,” prompting the agent to scan the repository, modify multiple files, and continuously refine its changes until all tests successfully pass. This represents the current focus for highly capable tools like Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex.

Industry observers and developers are encouraged to contemplate the potential characteristics of the subsequent wave in AI’s evolution within software development.

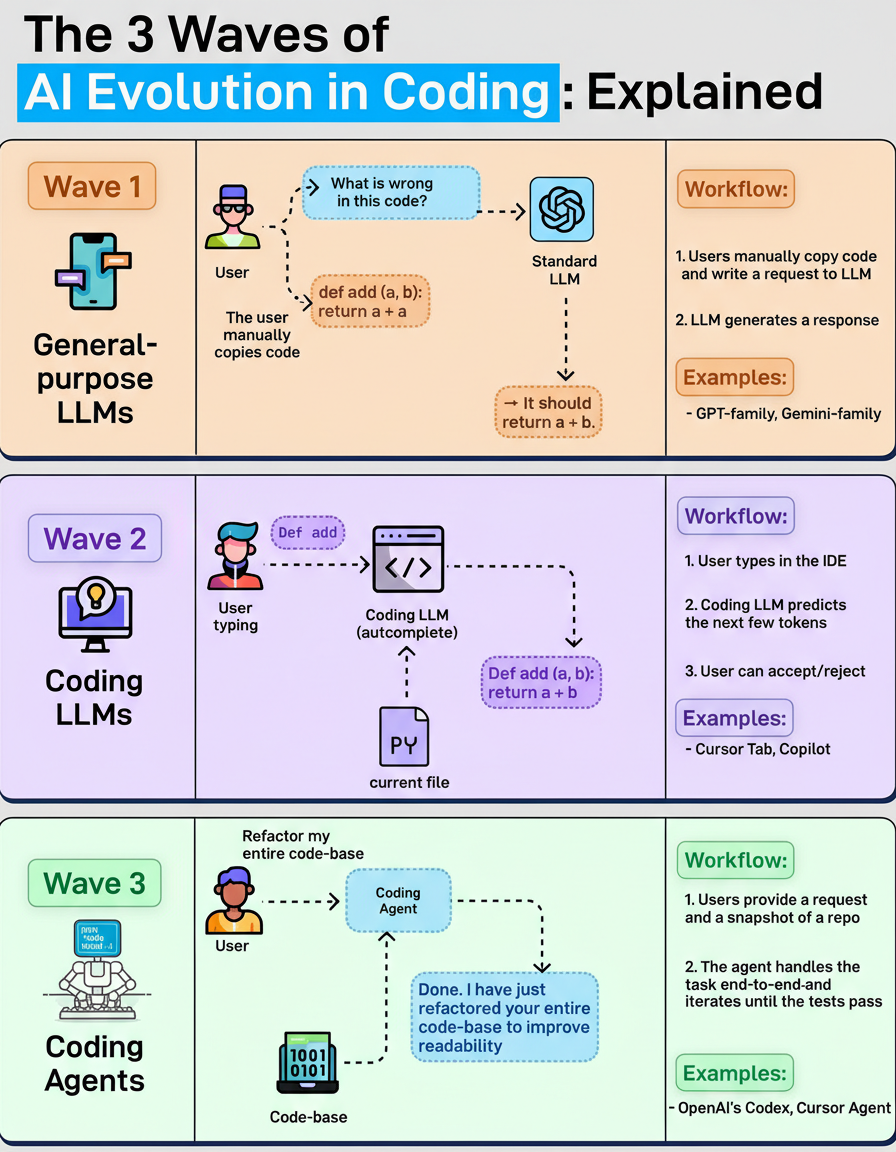

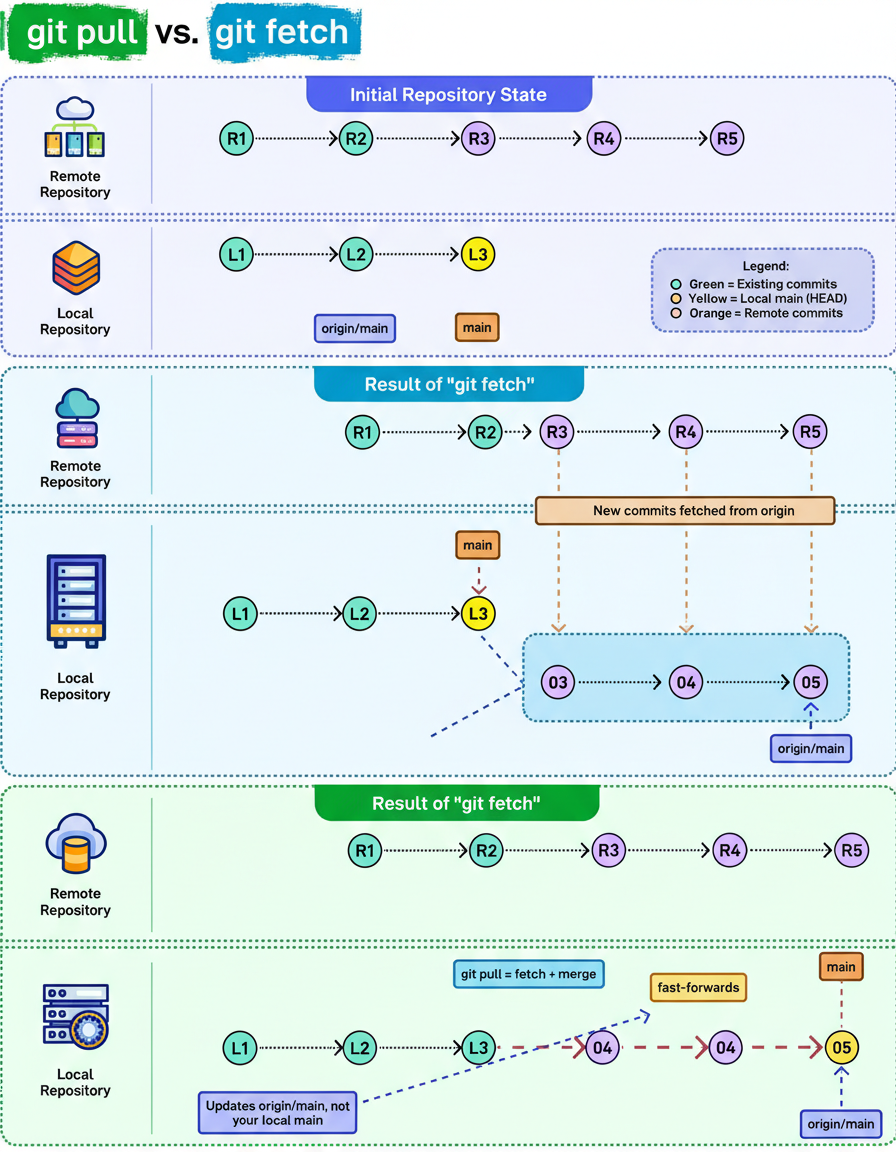

The distinction between the “git pull” and “git fetch” commands frequently causes confusion, even among seasoned developers. Despite their superficial resemblance, these commands operate with fundamentally different behaviors at a technical level.

An examination of how each command modifies a repository state reveals their operational differences:

Consider an initial scenario where a local repository lags slightly behind its remote counterpart. The remote repository contains new commits, specifically R3, R4, and R5, whereas the local “main” branch currently concludes at commit L3.

The “git fetch” command is designed to retrieve new commits from the remote repository without directly altering the current working branch. Its sole function is to update the “origin/main” reference. This operation can be conceptualized as an instruction to display changes without immediate application.

“Git pull” represents a composite operation, effectively combining “fetch” and “merge” commands. It downloads the latest commits and proceeds to immediately integrate them into the local branch. Consequently, this command updates both the “origin/main” reference and the local “main” branch. It functions as an directive to retrieve updates and apply them without delay.

Developers often debate the preferred usage between “git pull” and “git fetch” in their daily workflows.

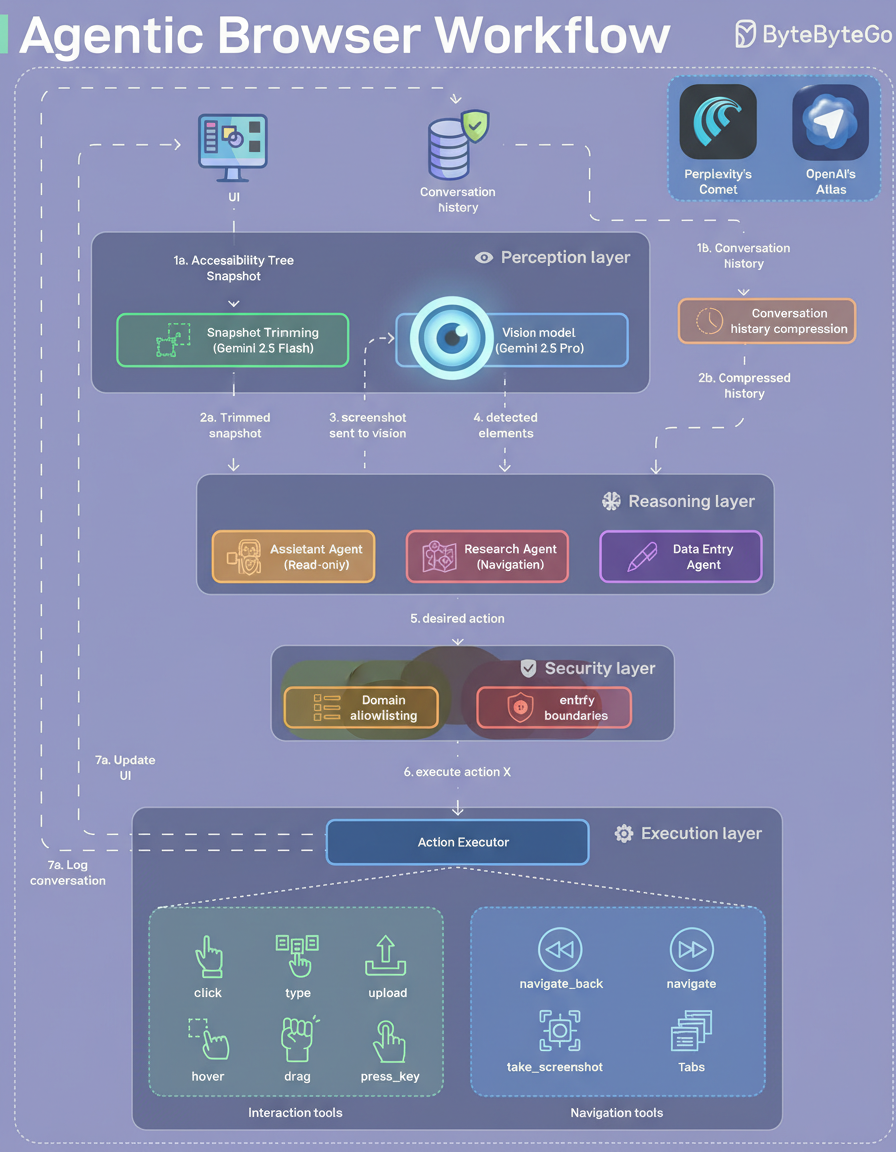

Agentic browsers are characterized by the integration of an embedded agent capable of interpreting web page content and executing actions within a user’s browser environment.

The architecture of most agentic browsers typically comprises four primary functional layers.

The perception layer is responsible for translating the graphical user interface into a format consumable by the underlying model. This process commences with an accessibility tree snapshot. Should this tree prove incomplete or ambiguous, the agent captures a screenshot, dispatches it to a vision model (e.g., Gemini Pro) for the extraction of structured UI elements, and subsequently utilizes this information to determine the appropriate subsequent action.

Within the reasoning layer, specialized agents are employed for distinct tasks such as read-only browsing, navigation, and data entry. This segregation of roles enhances overall system reliability and facilitates the application of specific safety protocols tailored to each agent.

A crucial security layer is implemented to enforce domain allowlisting and establish deterministic operational boundaries. These boundaries include restricting certain actions and incorporating confirmation steps, all designed to mitigate the risk of prompt injection attacks.

The execution layer orchestrates the deployment of various browser tools, encompassing actions like clicking, typing, file uploads, navigation, screenshot capture, and tab management. Following each executed step, this layer is responsible for refreshing the browser’s state.

A pertinent question for the broader tech community concerns the current reliability of agentic browsers and their readiness for deployment at scale.