Developers often encounter situations where code performs flawlessly in testing environments but struggles in production, taking extended times to load pages or failing under real-world data volumes.

A common inclination is to postpone optimization or delegate performance tuning to specialists. Both perspectives are often mistaken. Producing reasonably fast code does not necessitate advanced computer science expertise or extensive experience. Instead, it demands an understanding of where performance is crucial and a grasp of fundamental principles.

The well-known adage regarding premature optimization as “the root of all evil” is frequently cited by many developers. However, this statement from Donald Knuth is almost invariably taken out of its original context. The complete quotation specifies: “One should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet one should not pass up opportunities in that critical 3%”.

This article focuses on that crucial 3%, examining methods to estimate performance impact, determine optimal measurement times, identify key indicators, and apply practical techniques effective across various programming languages.

One of the most valuable proficiencies in performance-aware development is the capacity to estimate approximate performance costs prior to code implementation. Precise measurements are not essential at this juncture; merely comprehending orders of magnitude is sufficient.

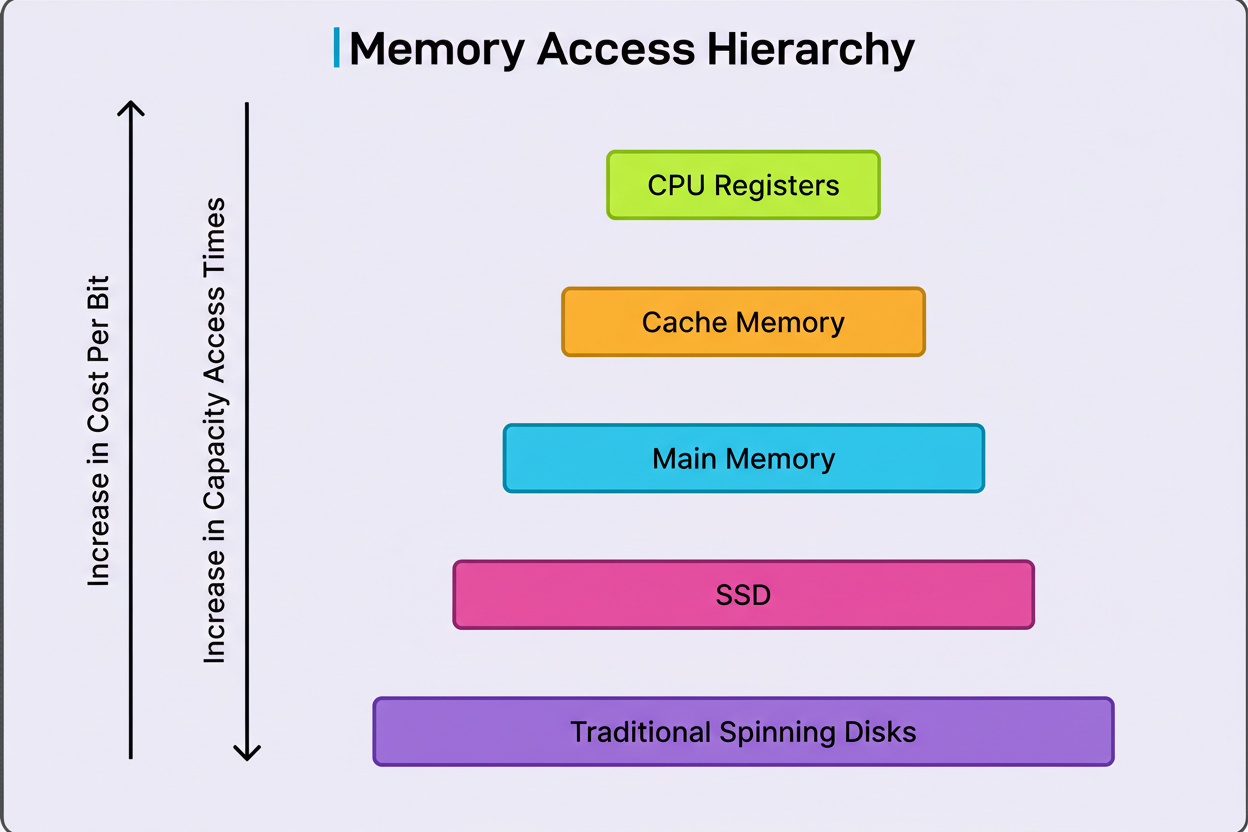

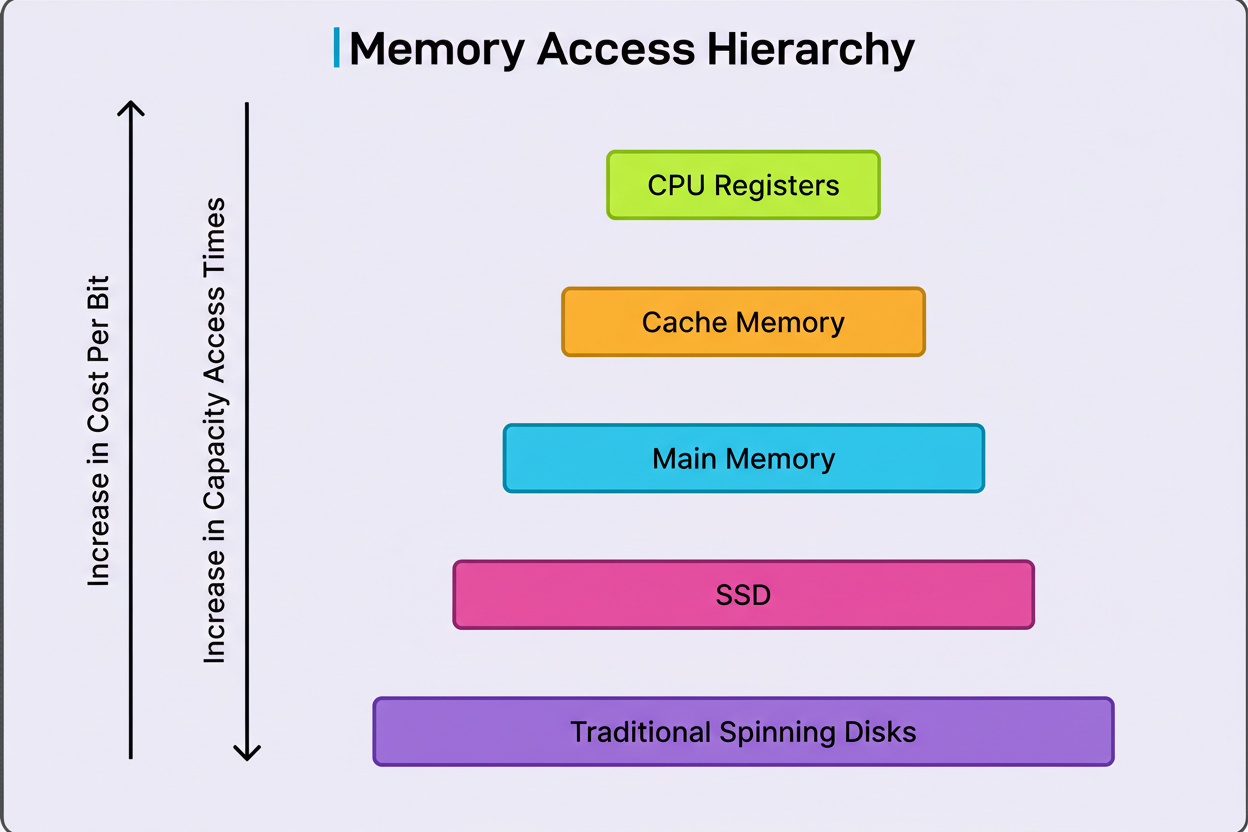

Computer operations can be conceptualized as existing within distinct speed categories. The fastest category involves CPU cache access, occurring in nanoseconds. These operations utilize data already residing in close proximity to the processor, readily available for use. A slower category involves accessing main memory (RAM), which typically requires approximately 100 times more duration than cache access. Progressing further down the hierarchy, reading from an SSD might demand 40,000 times longer than a cache access. Network operations consume even more time, and traditional spinning disk seeks can be millions of times slower than processing cached data.

This differentiation is significant because when designing a system tasked with processing a million records, the architectural approach should vary considerably based on whether the data originates from memory, disk, or a network call. A straightforward estimation can indicate whether a proposed solution will require seconds, minutes, or hours.

Consider a practical illustration. If one needs to process one million user records, and each record necessitates a network call to a database taking 50 milliseconds, the total duration would be 50 million milliseconds, equating to approximately 14 hours. Nevertheless, if these requests can be batched, fetching 1000 records per call, the requirement reduces to only 1000 calls, completing in about 50 seconds.

Intuition regarding performance bottlenecks is frequently inaccurate. Developers might dedicate significant time to optimizing a function perceived as slow, only to ascertain through profiling that an entirely different segment of the code constitutes the actual issue.

Therefore, the primary principle of performance optimization dictates measuring initially and optimizing subsequently. Contemporary programming languages and platforms offer superior profiling tools that precisely illustrate where a program expends its execution time. These tools monitor CPU utilization, memory allocations, I/O operations, and lock contention within multi-threaded applications.

The fundamental approach to profiling is uncomplicated.

Initially, a program is executed under a profiler utilizing realistic workloads, rather than simplified examples. The resulting profile reveals which functions consume the most processing time.

Occasionally, however, a flat profile is encountered. This occurs when no single function predominantly impacts the runtime. Instead, numerous functions each contribute a minor percentage. This scenario is prevalent in established codebases where apparent bottlenecks have already been addressed. When confronted with a flat profile, the strategy for optimization shifts. The focus moves to identifying patterns across multiple functions, evaluating structural modifications higher in the call chain, or concentrating on aggregating numerous minor enhancements rather than pursuing a singular, substantial improvement.

The crucial takeaway is that data should inform optimization decisions.

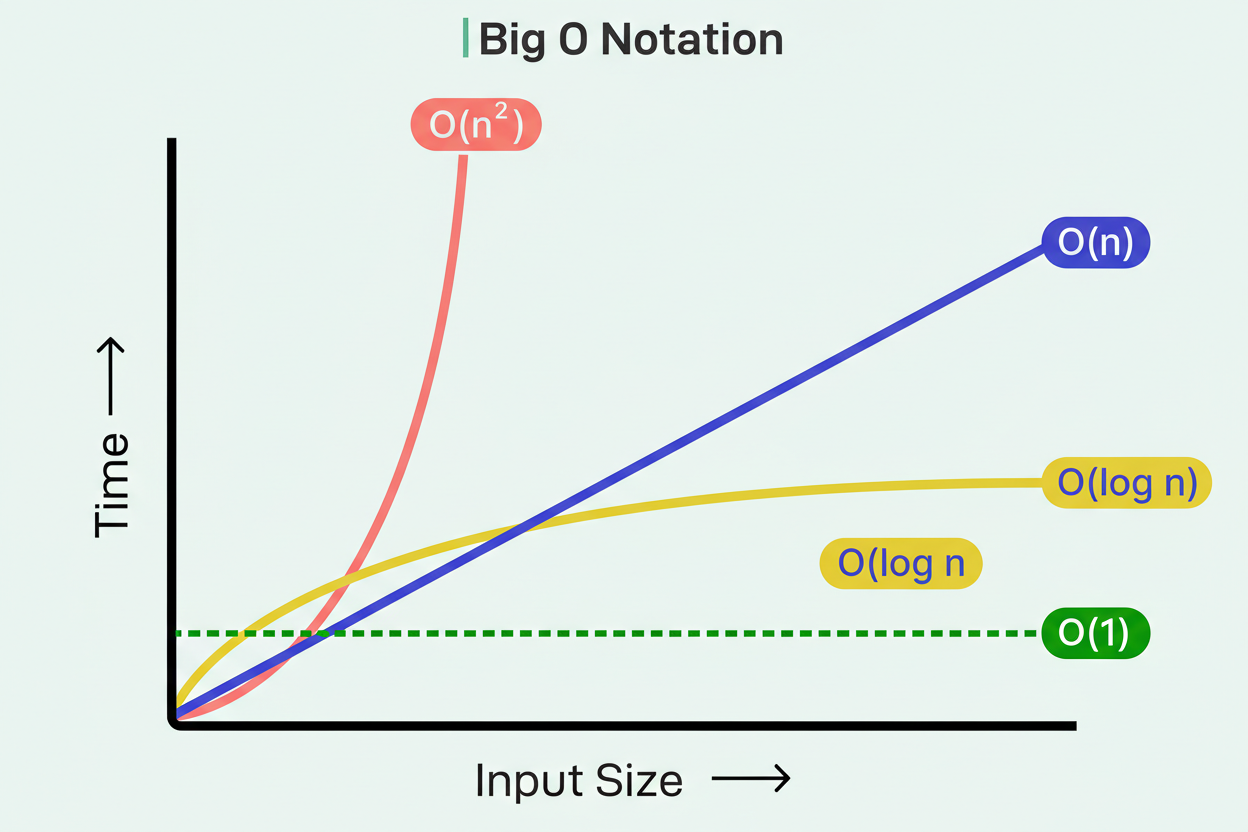

The most significant performance enhancements almost invariably stem from selecting superior algorithms and data structures. A more efficient algorithm can yield a 10x or 100x speedup, considerably overshadowing any micro-optimizations implemented.

Consider a typical scenario: an operation requires identifying items present in a first list that also exist in a second list. The naive strategy employs nested loops. For each item in list A, a scan is performed through all of list B to find a match. If each list contains 1000 items, this potentially entails one million comparisons, representing an O(N²) algorithm, where computational effort scales with the square of the input size.

A more effective methodology involves transforming list B into a hash table, then performing lookups for each item from list A. Hash table lookups are generally O(1), or constant time; thus, 1000 lookups are performed instead of a million comparisons. The total computational effort becomes O(N) rather than O(N²). For lists comprising 1000 items, this could translate to completion in milliseconds instead of seconds.

Another frequent algorithmic improvement incorporates caching or precomputation. If the same value is computed repeatedly, particularly within a loop, it should be calculated once and its result stored.

The crucial aspect of identifying algorithmic issues in a profile involves observing functions that consume the majority of the runtime and contain nested loops, or those that repeatedly search or sort identical data. Prior to delving into the optimization of such code, one should evaluate whether a fundamentally distinct approach could accomplish the task with less overall work.

Contemporary CPUs exhibit remarkable speed, yet their operations are confined to data residing within their compact, exceptionally fast caches. When requisite data is absent from the cache, it must be retrieved from main memory, a process significantly slower. This discrepancy is so profound that the arrangement of data in memory frequently holds more importance than the algorithmic complexity of the code.

The accompanying diagram illustrates this concept:

The foundational principle here is locality: data that is accessed concurrently should be co-located in memory. When the CPU retrieves data from memory, it does not fetch merely a single byte; it retrieves an entire cache line, typically 64 bytes. If related data is dispersed across memory, cache lines are inefficiently utilized, and new data must be constantly fetched. If data is compactly arranged, multiple pieces of related data are obtained within each cache line.

Consider two methods for storing a collection of user records:

One method involves an array of pointers, with each pointer directed to a user object allocated elsewhere in memory.

Alternatively, a single contiguous array can store all user objects sequentially.

The former approach dictates that accessing each user necessitates following a pointer, and each user object may reside on a distinct cache line. The latter approach implies that upon fetching the initial user, several subsequent users are likely already present in the cache.

This explains why arrays and vectors generally surpass linked lists in performance for most operations, notwithstanding the theoretical advantages of linked lists for insertions and deletions. The cache efficiency inherent in sequential access typically predominates.

Reducing the memory footprint is also beneficial. Smaller data structures enable more data to fit into the cache. If a 64-bit integer is employed for storing values that never surpass 255, memory is being wasted. Utilizing an 8-bit type instead permits fitting eight times as many values within the same cache line. Similarly, eliminating superfluous fields from frequently accessed objects can yield a measurable impact.

The access pattern also holds significance. Sequential access through an array is considerably faster than random access. If one is summing a million numbers stored in an array, the process is swift due to sequential access, allowing the CPU to anticipate subsequent data needs. If the identical numbers are in a linked list, each access mandates following a pointer to an unpredictable location, thereby undermining cache efficiency.

The practical inference is to favor contiguous storage (arrays, vectors) over scattered storage (linked lists, maps) when performance is critical. Related data should be maintained together and accessed sequentially whenever feasible.

Each instance of memory allocation incurs a cost. The memory allocator must locate available space, bookkeeping data structures require updates, and the new object typically necessitates initialization. Subsequently, upon an object’s obsolescence, it demands cleanup or destruction. In garbage-collected languages, the collector must track these objects and eventually reclaim them, a process that can induce perceptible delays.

Aside from the allocator overhead, individual allocations usually occupy distinct cache lines. Should numerous small objects be created independently, they become dispersed across memory, thereby diminishing cache efficiency as elaborated in the preceding section.

Frequent causes of excessive allocation encompass the creation of temporary objects within loops, the repeated resizing of containers as elements are appended, and the copying of data when it could be moved or merely referenced.

Container pre-sizing represents an efficacious methodology. If the eventual requirement for a vector with 1000 elements is known, that space should be reserved in advance. Failing to do so may result in the vector allocating space for 10 elements, then 20, then 40, and so forth as elements are added, duplicating all existing data each time.

Object reuse constitutes another uncomplicated advantage. If the same type of temporary object is instantiated and deallocated thousands of times in a loop, it should be created once prior to the loop and subsequently reused during each iteration, cleared as necessary. This practice is particularly crucial for intricate objects such as strings, collections, or protocol buffers.

Contemporary programming languages support “moving” data rather than duplicating it. Moving data transfers ownership without creating a copy. When large objects are passed between functions and the original is not required, moving proves considerably more economical than copying.

Various container types possess distinct allocation behaviors. Maps and sets typically allocate memory for each element individually. Vectors and arrays, conversely, are allocated in bulk. When performance is paramount, and a choice is being made between containers with comparable functionalities, the allocation pattern can be the determinative factor.

The most expedient code is that which is never executed. Prior to optimizing the execution of a task, one should ascertain whether the task is truly necessary or if its frequency can be reduced.

Several common strategies for achieving this include:

Establishing fast paths for prevalent scenarios is a potent technique. Within numerous systems, 80% of cases conform to a straightforward pattern, while 20% demand intricate processing. If the common case can be identified and an optimized path developed for it, the majority of operations accelerate, even if the complex case remains unaltered. For instance, if most strings within a system are short, optimization can be specifically targeted for short strings, while retaining the general implementation for longer ones.

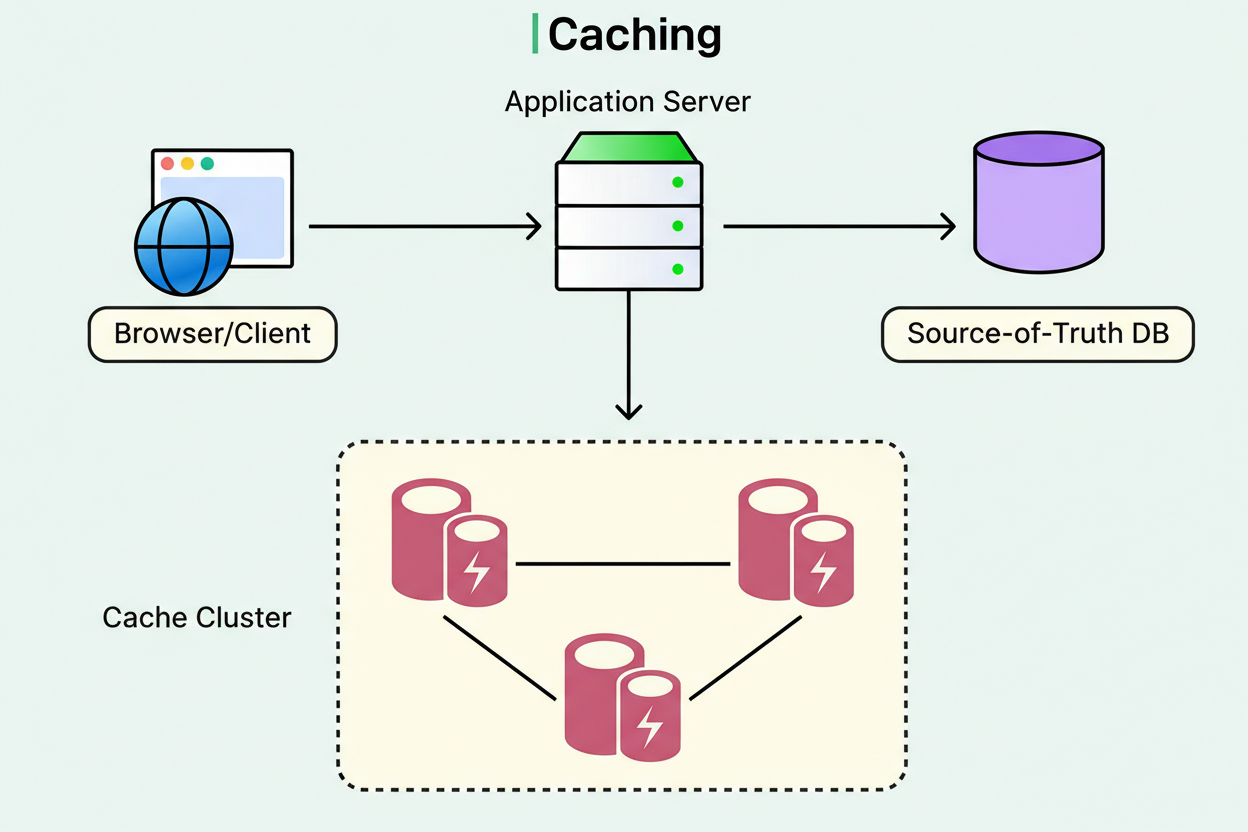

Precomputation and caching leverage the concept that computing a value once is more efficient than repeatedly calculating it. If a value remains constant throughout a loop, it should be computed prior to the loop, not during each iteration. If an expensive calculation yields a result that may be required multiple times, it should be cached subsequent to its initial computation.

Lazy evaluation postpones work until its actual necessity is confirmed. If a complex report is being constructed that a user might never request, it should not be generated eagerly during initialization. Analogously, if a sequence of items is being processed and an early exit might occur based on the initial items, all items should not be processed upfront.

Early exit involves verifying inexpensive conditions before costly ones and returning as soon as a conclusive answer is obtained. If user input is being validated and the primary validation check fails, expensive downstream processing should not be initiated. This fundamental principle can eliminate substantial amounts of superfluous work.

Ultimately, the choice exists between general and specialized code. General-purpose libraries accommodate all conceivable cases, which frequently renders them slower than code crafted for a single, specific scenario. If operating within a performance-critical section and employing a robust general solution, consideration should be given to whether a lightweight, specialized implementation would be adequate.

Certain performance considerations should become ingrained during code development, even prior to profiling.

When conceptualizing APIs, efficient implementation should be prioritized. Processing items in batches is typically more efficacious than processing them individually. Permitting callers to provide pre-allocated buffers can obviate allocations in performance-critical sections. Features should not be imposed on callers who do not require them. For instance, if the majority of data structure users do not necessitate thread-safety, synchronization should not be integrated into the structure itself. Instead, those requiring it should implement synchronization externally.

Hidden costs warrant attention. Logging statements can incur significant overhead even when logging is deactivated, as the check for logging enablement still consumes resources. If a logging function is invoked millions of times, its removal or a single logging level check outside the hot path should be considered. Likewise, error checking within tight loops can accumulate substantial cost. Where feasible, inputs should be validated at module boundaries rather than repeatedly checking identical conditions.

Each programming language possesses distinct performance characteristics for its standard containers and libraries. For example, within Python, list comprehensions and built-in functions generally surpass manual loops in speed. In JavaScript, typed arrays demonstrate considerably greater velocity than regular arrays for numerical data. In Java, ArrayList almost consistently outperforms LinkedList. In C++, vector is usually the optimal selection over list. Acquiring knowledge of these characteristics for the chosen language yields substantial benefits.

String operations are prevalent and frequently sensitive to performance. In numerous languages, string concatenation within a loop is costly because each concatenation generates a new string object. String builders or buffers address this issue by efficiently accumulating the result and forming the final string only once.

Not all code mandates optimization. The focus should not be on optimizing every component, but rather on the critical sections. The renowned Pareto principle applies in this context: approximately 20% of a codebase typically accounts for 80% of its runtime. The task is to identify and optimize this crucial 20%.

Performance is not the sole consideration. Code readability is also significant because other developers are responsible for its maintenance. Excessively optimized code can be challenging to comprehend and alter. Developer time possesses inherent value as well. Devoting a week to optimizing code that yields a daily saving of merely one second may not be a judicious investment.

The appropriate methodology entails first writing clear, correct code. Subsequently, measurements should be conducted to pinpoint actual bottlenecks, followed by optimizing the critical paths until specified performance targets are met. At that juncture, the optimization process ceases. Further optimization yields diminishing returns and incurs increasing costs in terms of code complexity.

Nevertheless, certain situations distinctly necessitate performance scrutiny. Code that executes millions of times, such as functions within the hot path of request handling, warrants optimization. User-facing operations should provide an instantaneous experience, as perceived performance influences user satisfaction. Inefficient background processing at scale can consume vast resources, directly affecting operational expenditures. Resource-constrained environments, including mobile devices or embedded systems, require meticulous optimization to function effectively.

Crafting performant code necessitates cultivating an intuition regarding critical performance areas and acquiring foundational principles applicable across diverse languages and platforms.

The process commences with estimation. Comprehending the approximate costs of prevalent operations facilitates intelligent architectural choices prior to code development. Measurement reveals genuine issues, frequently surprising developers by exposing unsuspected bottlenecks. Superior algorithms and data structures offer order-of-magnitude enhancements that significantly overshadow micro-optimizations. Memory layout and allocation patterns hold greater significance than many developers acknowledge. And frequently, the most straightforward performance gain lies in simply avoiding superfluous work.

The requisite shift in mindset involves transitioning from viewing performance as a post-development remediation to a consideration integrated throughout the development lifecycle. Obsessing over every line of code is unnecessary; however, fostering an awareness of the performance implications of design and implementation choices is crucial.