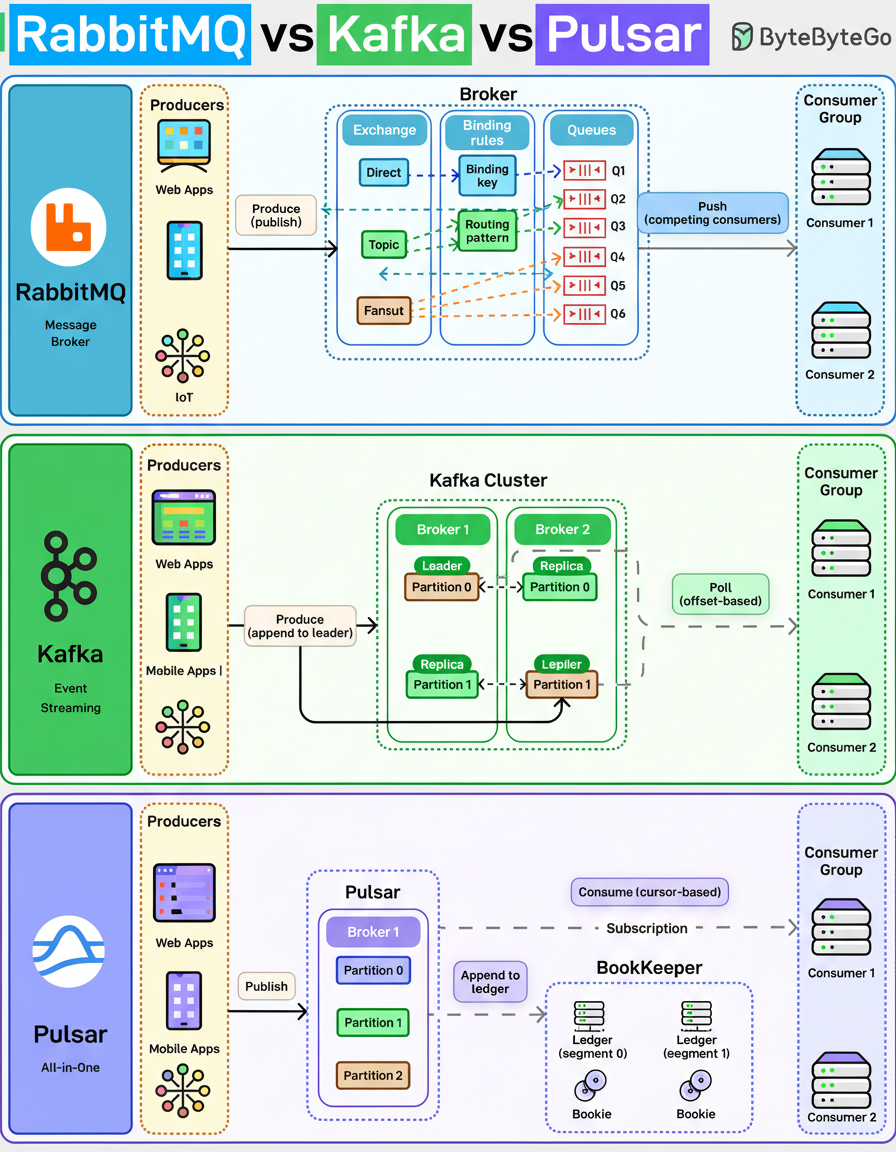

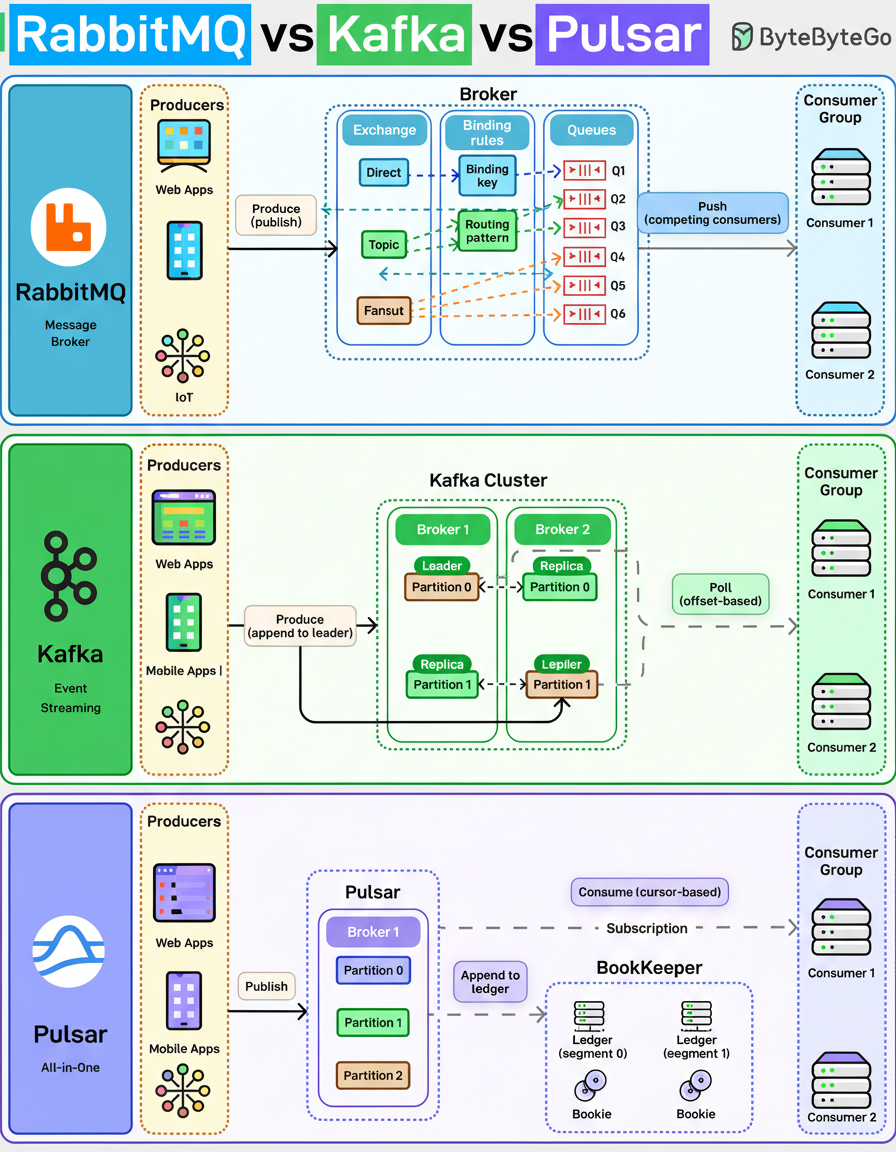

RabbitMQ, Kafka, and Pulsar each facilitate message movement, yet they address fundamentally distinct challenges within distributed system architectures.

This presented diagram appears straightforward; however, it encapsulates three highly divergent conceptual models crucial for constructing robust distributed systems.

RabbitMQ functions as a classic message broker. Producers publish messages to exchanges, which then route these messages to specific queues. Consumers subsequently compete to process the messages from these queues.

Messages are actively pushed to consumers, acknowledged upon receipt, and then removed from the system. This architecture proves highly effective for task distribution, handling requests, and managing workflows where a “do this once” guarantee is paramount.

Kafka employs a distinct model, operating not as a traditional queue but as a distributed log for event streaming. Producers append events to partitions, and data persists based on defined retention policies, independent of consumption status. Consumers retrieve data using offsets, allowing for the replay of historical events, a key aspect for capacity planning and data recovery.

This design makes Kafka exceptionally suitable for event streaming architectures, real-time analytics, and data pipelines where diverse teams require access to the same data at varying times.

Pulsar endeavors to integrate the capabilities of both models. Brokers are responsible for serving traffic, while BookKeeper ensures data durability by storing it in a persistent ledger. Consumers manage their position using cursors rather than offsets.

This architectural separation enables Pulsar to scale storage and compute resources independently, thereby accommodating both streaming and queue-like messaging patterns effectively.

The selection among these systems is not primarily driven by considerations of speed or current popularity. Instead, the critical factors involve understanding desired data flow, required data retention periods, and the anticipated number of times data will be read.

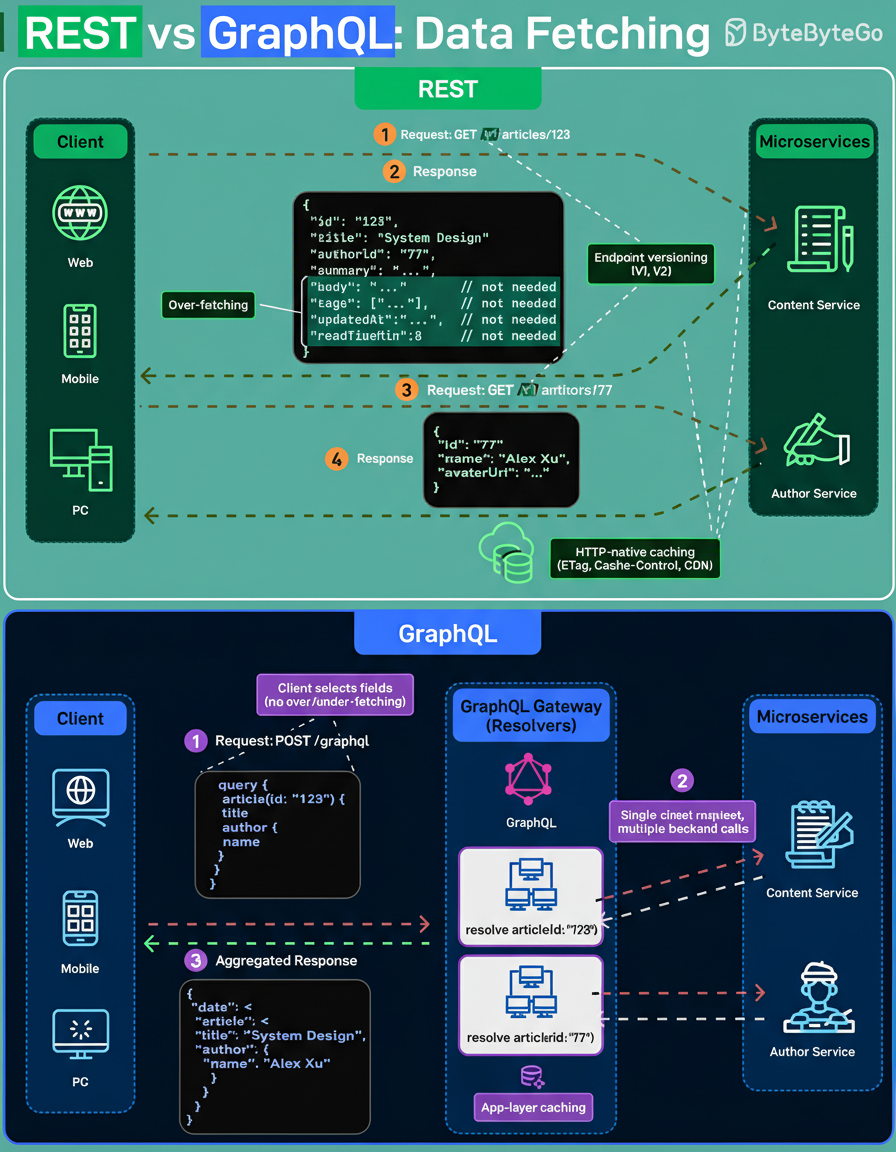

With a RESTful architecture, the server dictates the structure of the response. A call to an endpoint such as “/v1/articles/123” yields the data pre-defined for that specific resource. Should related data be required, additional requests are typically necessary. Furthermore, if the returned payload is more extensive than strictly needed, consumers must contend with data over-fetching.

HTTP provides robust primitives for REST, including clear resource boundaries, versioning through URLs, and native caching mechanisms facilitated by ETag, Cache-Control headers, and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs).

Conversely, GraphQL empowers the client to define the precise shape of the response. Clients send a single query specifying the exact fields desired. Behind the scenes, a GraphQL gateway orchestrates requests to multiple underlying services, executes resolvers, and aggregates the final response.

The complexity in GraphQL shifts from the client-side to the server-side. While caching capabilities exist, they are typically implemented at the application layer, often through persisted queries or response caching, rather than being automatically handled by the HTTP layer.

Neither approach is inherently superior. REST is optimized for architectural simplicity, inherent cacheability, and explicit ownership of resources. GraphQL, on the other hand, prioritizes flexibility, client-driven data requirements, and efficient data aggregation across various services.

The determination of when REST is sufficient and when GraphQL becomes advantageous hinges on specific project demands and architectural goals, particularly concerning data retrieval flexibility and caching strategies.