For an extended period, artificial intelligence systems operated as specialists, each confined to a single sensory modality. For instance, computer vision models could identify objects within photographs but lacked the capacity to describe their observations. Natural language processing systems were capable of generating eloquent prose yet remained unable to interpret images. Similarly, audio processing models could transcribe spoken language but possessed no visual context. This fragmentation fundamentally diverged from human cognition, which is inherently multimodal. Humans do not exclusively process text or merely perceive images; instead, they simultaneously observe facial expressions while discerning tone of voice, connecting the visual form of a dog with its bark and the written word “dog.”

To develop AI that truly functions within real-world environments, these distinct sensory channels necessitated convergence. Multimodal Large Language Models (LLMs) embody this convergence. For example, GPT-4o demonstrates the ability to respond to voice input in merely 232 milliseconds, aligning with human conversational speed. Google’s Gemini is capable of processing a full hour of video within a single prompt. These advanced capabilities emerge from a singular, unified neural network engineered to simultaneously perceive, hear, and read. This article explores the fundamental question of how a single AI system comprehends such fundamentally disparate data types.

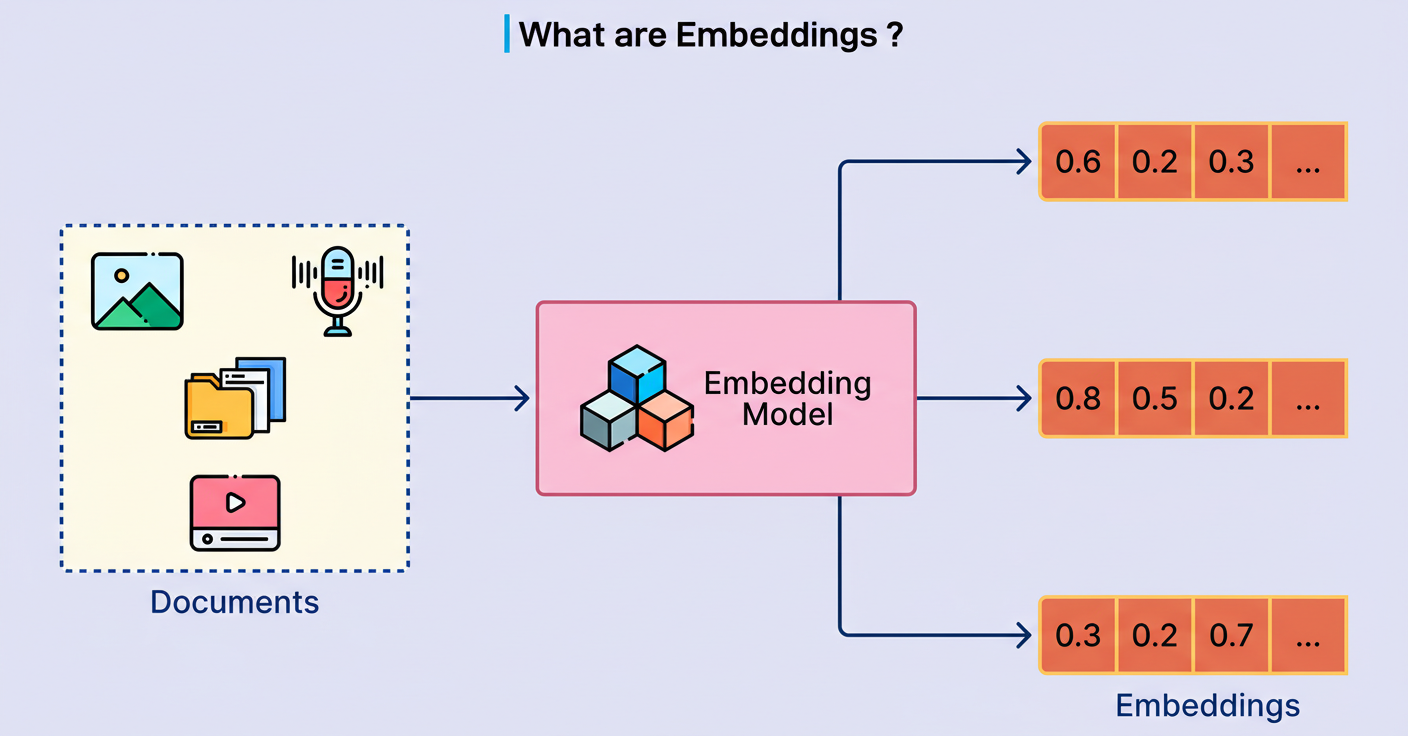

The fundamental innovation underpinning multimodal LLMs lies in a straightforward principle: every input type, encompassing text, images, or audio, is transformed into an identical mathematical representation known as embedding vectors. Analogous to how human brains convert light photons, sound waves, and written symbols into uniform neural signals, multimodal LLMs translate diverse data types into vectors that occupy a shared mathematical space.

Consider a practical illustration: a photograph of a dog, the spoken utterance “dog,” and the written text “dog” are all converted into points within a high-dimensional mathematical space. These points naturally cluster in proximity, signifying their representation of the identical concept.

This unified representation facilitates what researchers term cross-modal reasoning. The model gains the capacity to understand that a barking sound, an image of a golden retriever, and the sentence “the dog is happy” all pertain to the same underlying concept. Consequently, the model does not require separate systems for each modality. Instead, it processes all inputs through a single architecture that treats visual patches and audio segments precisely like text tokens.

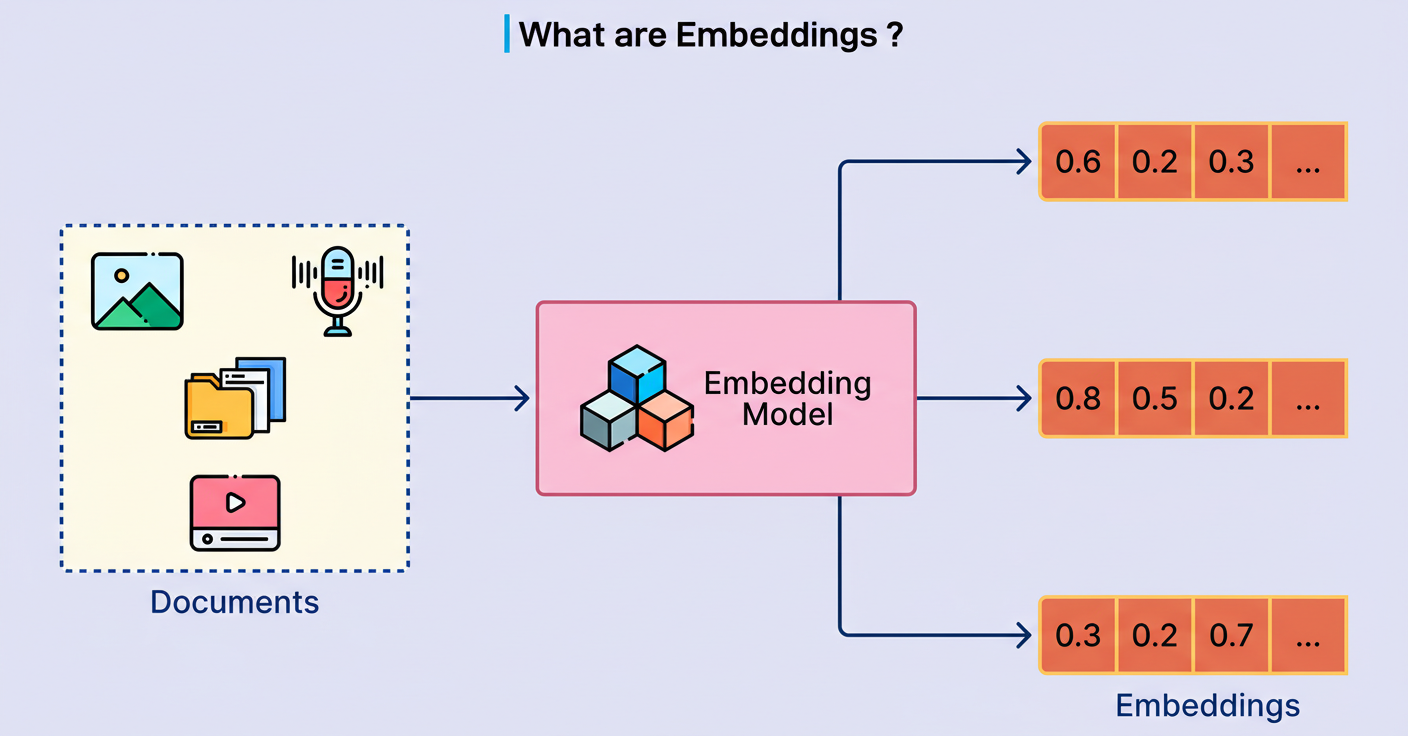

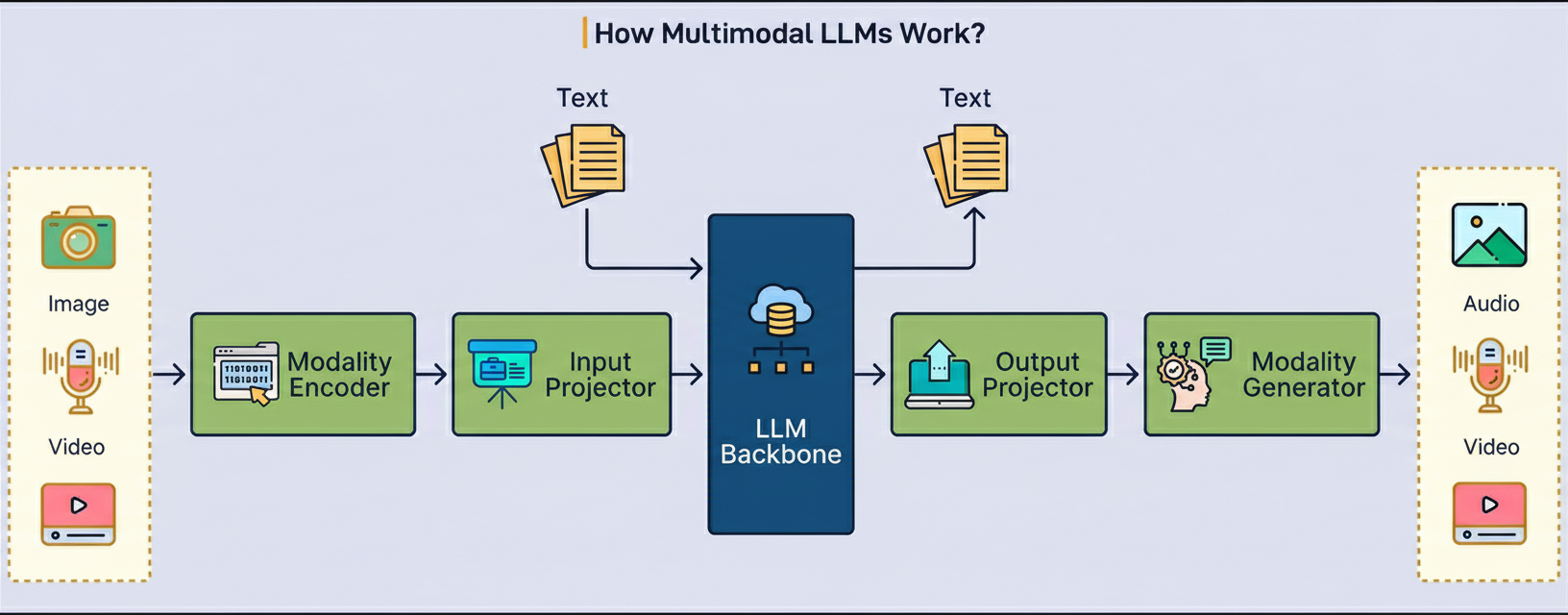

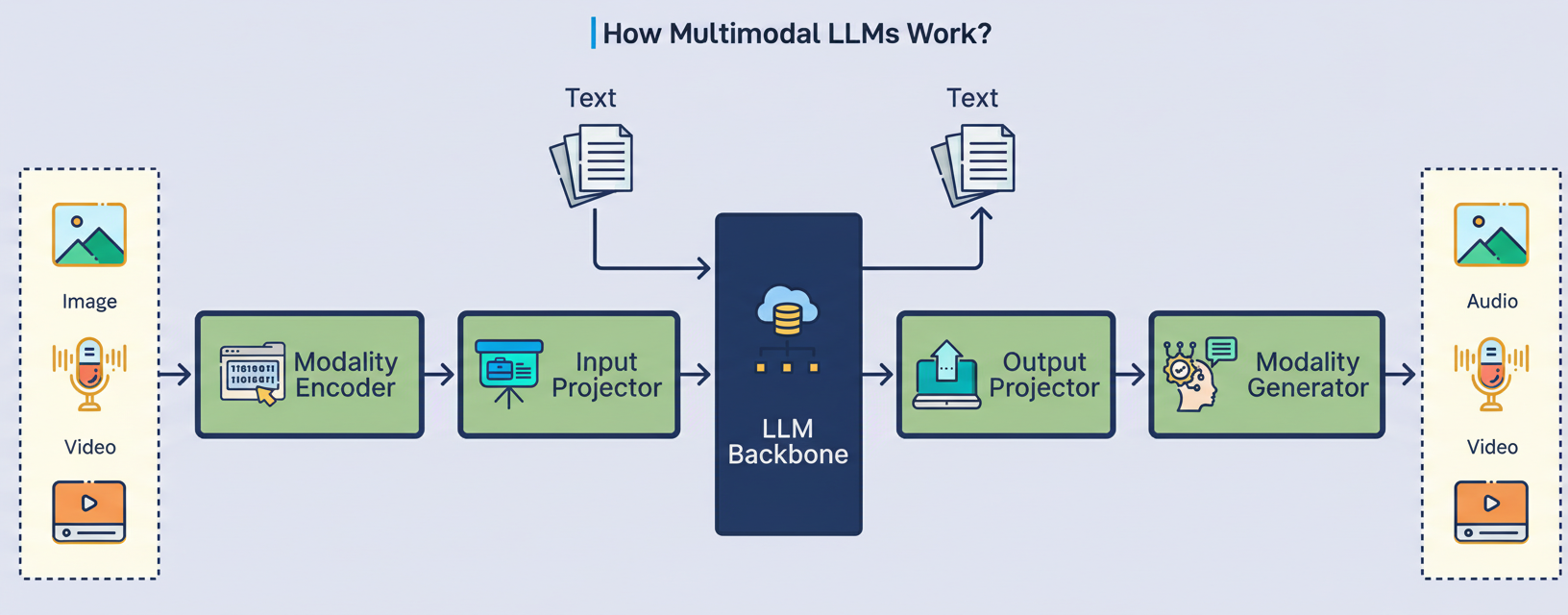

The subsequent diagram illustrates a high-level overview of a multimodal LLM’s operational framework:

Contemporary multimodal LLMs are composed of three essential components that collaboratively process diverse inputs.

The initial component is responsible for translating raw sensory data into preliminary mathematical representations.

Vision Transformers process images by treating them akin to sentences, partitioning photographs into small patches and processing each patch as if it were a word.

Audio encoders convert sound waves into spectrograms, which are visual-like representations depicting the evolution of frequencies over time.

These encoders are typically pre-trained on extensive datasets, enabling them to achieve high proficiency in their specialized functions.

The second component functions as an intermediary bridge. Although both encoders generate vectors, these vectors reside in distinct mathematical spaces. Specifically, the vision encoder’s representation of “cat” occupies a different geometric region than the language model’s representation of the word “cat.”

Projection layers serve to align these disparate representations into the common space where the language model operates. Frequently, these projectors exhibit surprising simplicity, sometimes consisting merely of a linear transformation or a compact two-layer neural network. Despite their architectural simplicity, they are indispensable for enabling the model to comprehend visual and auditory concepts.

The third component constitutes the core Large Language Model (LLM), such as GPT or LLaMA.

This component acts as the central “brain” responsible for actual reasoning and response generation. It receives all inputs as sequences of tokens, irrespective of whether these tokens originated from text, image patches, or audio segments.

The language model processes these tokens identically through the same transformer architecture that powers text-only models. This unified processing capability allows the model to reason across modalities as fluidly as it handles pure text inputs.

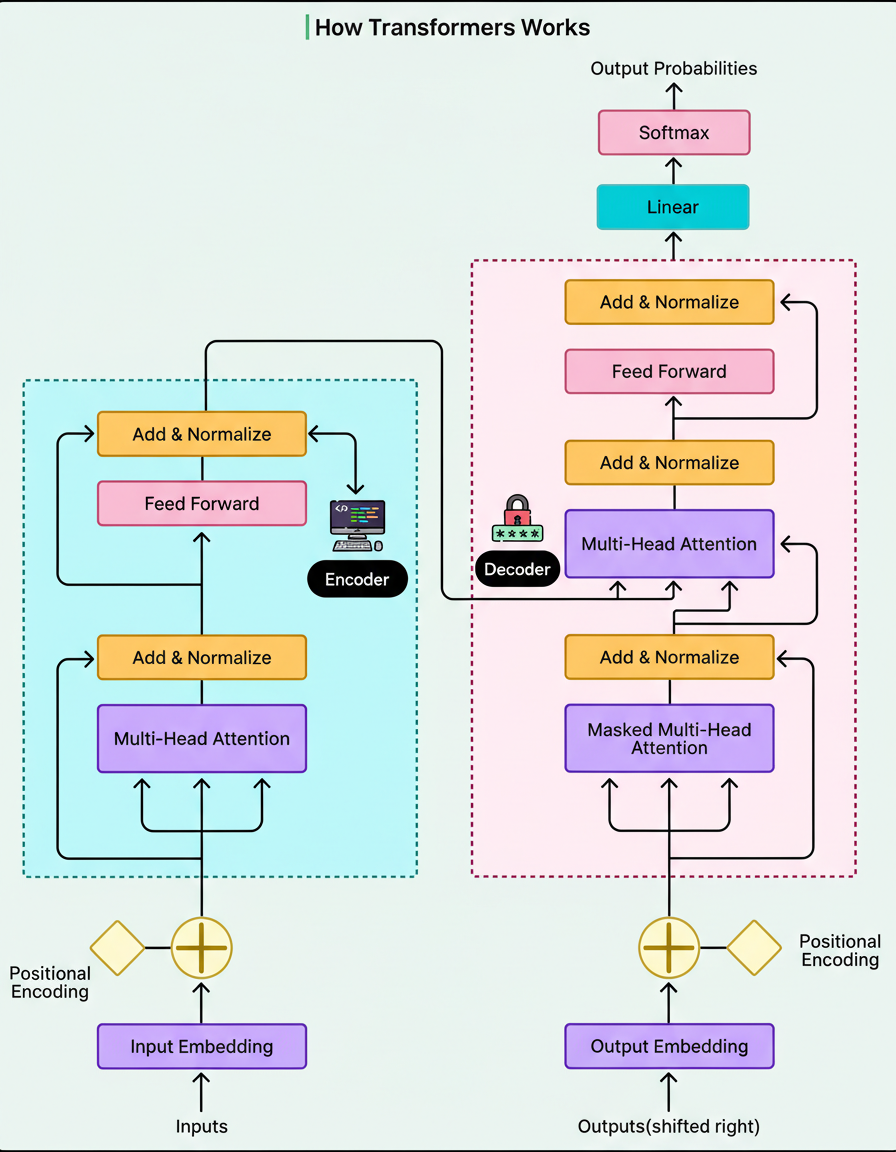

The diagram below depicts the transformer architecture:

The breakthrough that enabled modern multimodal vision originated from a 2020 research paper famously titled: “An Image is Worth 16×16 Words.” This publication introduced the paradigm of processing images precisely like sentences by treating small patches as individual tokens.

This intricate process unfolds through several distinct steps:

First, the image is systematically divided into a grid of fixed-size patches, typically 16×16 pixels each.

A standard 224×224 pixel image, for example, yields approximately 196 distinct patches, each representing a small square region.

Each patch undergoes a flattening transformation from a 2D grid into a 1D vector of numbers, which represent pixel intensities.

Positional embeddings are subsequently appended, providing the model with spatial information regarding each patch’s origin within the original image.

These patch embeddings then propagate through transformer layers, where attention mechanisms facilitate inter-patch learning and contextualization.

The attention mechanism is precisely where understanding emerges. A patch depicting a dog’s ear learns its connectivity to adjacent patches showcasing the dog’s face and body. Patches illustrating a beach scene learn to associate with one another to represent the broader context of sand and water. By the final layer, these visual tokens encapsulate rich contextual information, enabling the model to comprehend not merely “brown pixels” but rather “golden retriever sitting on beach.”

A second pivotal innovation was CLIP, an architecture developed by OpenAI. CLIP fundamentally transformed vision encoder training by altering its core objective. Instead of training on explicitly labeled image categories, CLIP was trained on 400 million pairs of images and their corresponding text captions sourced from the internet.

CLIP employs a contrastive learning methodology. Given a batch of image-text pairs, it computes embeddings for all images and all associated text descriptions. The primary objective is to maximize the similarity between embeddings of correctly matched image-text pairs while simultaneously minimizing the similarity between incorrect pairings. Consequently, an image of a dog should yield a vector spatially close to the caption “a dog in the park” but distant from “a plate of pasta.”

Audio data presents unique challenges for language models.

Unlike textual data, which naturally segments into discrete words, or visual data, which can be partitioned into spatial patches, sound is inherently continuous and temporal. For instance, a 30-second audio clip sampled at 16,000 Hz comprises 480,000 individual data points. Directly inputting such a massive stream of numbers into a transformer is computationally infeasible and inefficient. The resolution necessitates converting audio into a more manageable representation.

The key innovation involves transforming audio into spectrograms, which are essentially visual representations of sound. This process entails several mathematical transformations:

The extended audio signal is segmented into minute, overlapping windows, typically 25 milliseconds each.

A Fast Fourier Transform extracts the frequencies present within each window.

These frequencies are then mapped onto the mel scale, which aligns with human hearing sensitivity by allocating greater resolution to lower frequencies.

The outcome is a 2D heat map where time progresses along one axis, frequency along the other, and color intensity denotes volume.

This mel-spectrogram presents as an image to the AI model. For example, a 30-second audio clip might generate an 80×3,000 grid, effectively a visual representation of acoustic patterns that can be processed similarly to photographs. Once audio is converted into a spectrogram, models can apply the same techniques employed for vision. The Audio Spectrogram Transformer divides the spectrogram into patches, mirroring the division of an image. For instance, models such as Whisper, which were trained on 680,000 hours of multilingual audio, demonstrate exceptional proficiency in this transformation.

The training regimen progresses through distinct stages:

Training a multimodal LLM typically unfolds in two discrete stages.

The initial stage focuses exclusively on alignment, instructing the model that visual and textual representations of identical concepts should exhibit similarity. During this phase, both the pre-trained vision encoder and the pre-trained language model remain immutable. Only the weights of the projection layer undergo updates through the training process.

Alignment alone proves insufficient for practical application. A model might accurately describe an image’s contents but fail at intricate tasks such as answering “Why does the person look sad?” or “Compare the two charts.”

Visual instruction tuning addresses this limitation by training the model to execute sophisticated multimodal instructions.

During this stage, the projection layer continues its training while the language model is also updated, frequently employing parameter-efficient methods. The training data transitions to instruction-response datasets formatted as conversational exchanges.

A significant innovation in this area involved leveraging GPT-4 to synthesize training data. Researchers provided GPT-4 with textual descriptions of images and prompted it to generate realistic conversations pertaining to those images. Training on this synthetic yet high-quality data effectively distills GPT-4’s reasoning capabilities into the multimodal model, thereby teaching it to engage in nuanced visual dialogue rather than merely describing visual content.

Multimodal LLMs achieve their remarkable capabilities through an overarching unifying principle. By transforming all inputs into sequences of embedding vectors that inhabit a shared mathematical space, a single transformer architecture can engage in reasoning across modalities as seamlessly as it processes language in isolation.

The architectural innovations underpinning this capability represent substantial advancements: Vision Transformers treating images as visual sentences, contrastive learning aligning modalities without explicit labels, and cross-attention facilitating selective information retrieval across diverse data types.

The trajectory of future development points towards any-to-any models capable of both understanding and generating all modalities. This envisions a model that can concurrently output text, generate images, and synthesize speech within a singular response.