The evolution of Netflix beyond a mere streaming service, encompassing live events, mobile gaming, and ad-supported subscription plans, has introduced unforeseen technical complexities.

To comprehend the underlying difficulty, one can examine a representative member journey. For instance, a user might stream ‘Stranger Things’ on a smartphone, subsequently resume viewing on a smart TV, and later launch the ‘Stranger Things’ mobile game on a tablet device. These diverse activities, occurring across various devices and platform services at different intervals, collectively form a unified member experience.

Gaining insight into these cross-domain member journeys proved essential for crafting tailored user experiences. Nevertheless, Netflix’s existing architectural design presented obstacles to this endeavor.

Netflix employs a microservices architecture, comprising hundreds of services independently developed by distinct teams. Each service possesses the autonomy for independent development, deployment, and scaling, allowing teams to select optimal data storage technologies. A drawback emerges when individual services manage their own data, leading to information silos. For example, video streaming data resides in one database, gaming data in another, and authentication data is maintained separately. While conventional data warehouses aggregate this information, the data frequently settles into disparate tables and undergoes processing at varying intervals.

The manual aggregation of information from numerous siloed databases became an unmanageable task. Consequently, the Netflix engineering team sought an alternative methodology for processing and storing interconnected data, prioritizing rapid query capabilities. A graph representation was selected for this purpose, based on the subsequent rationales:

Firstly, graph structures facilitate swift relationship traversals, circumventing the need for computationally intensive database joins.

Secondly, graphs exhibit high adaptability to the emergence of new connections, requiring minimal schema modifications.

Thirdly, graphs inherently support pattern detection. The identification of concealed relationships and cyclical patterns proves more efficient through graph traversals compared to isolated data lookups.

These considerations prompted Netflix to develop the Real-Time Distributed Graph (RDG). This article examines the architectural design of RDG and the challenges encountered during its development by Netflix.

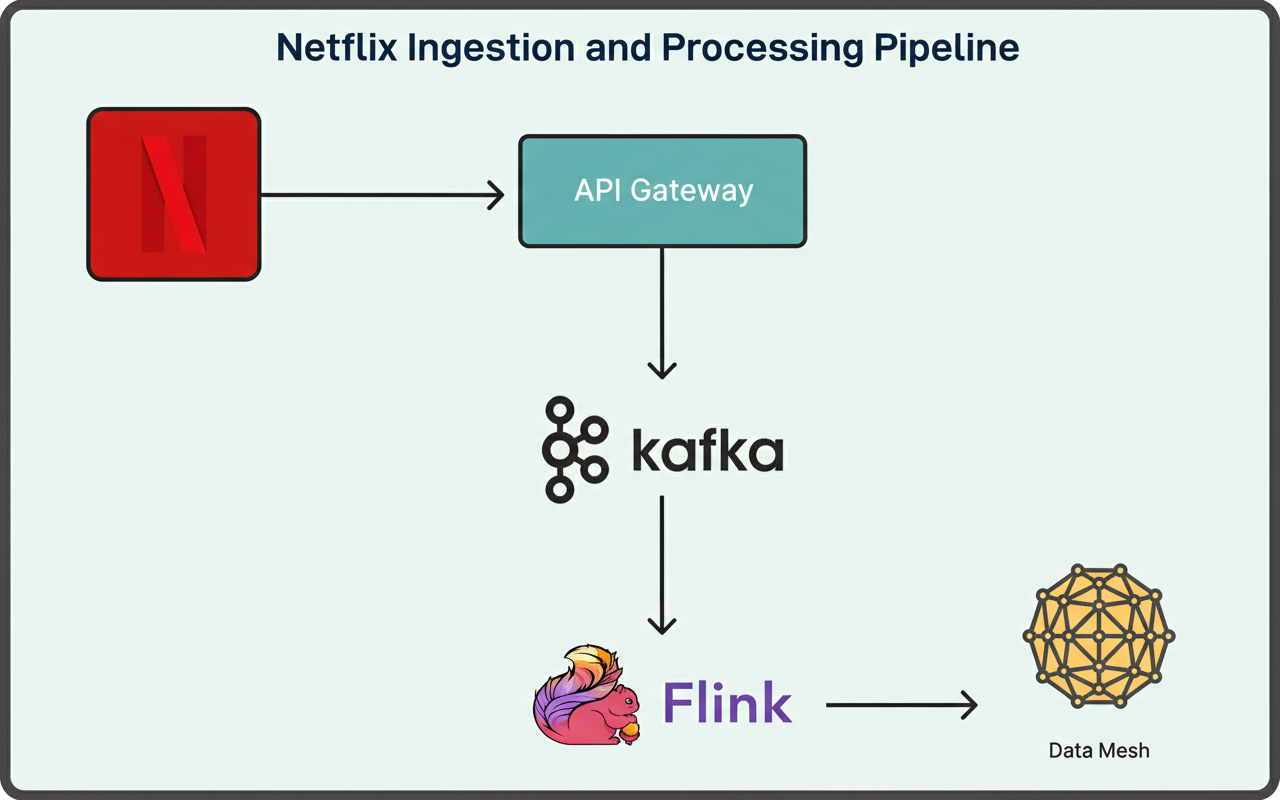

The RDG architecture encompasses three distinct layers: ingestion and processing, storage, and serving components. A visual representation is provided below:

Upon a member executing an action within the Netflix application, for instance, logging in or commencing a show, the API Gateway logs these occurrences as records into Apache Kafka topics.

Apache Kafka functions as the primary ingestion backbone, delivering persistent, replayable data streams consumable by downstream processors in real time. Netflix selected Kafka due to its precise alignment with requirements for constructing and updating the graph with negligible delay. Conventional batch processing systems and data warehouses were unable to furnish the low latency necessary for sustaining a current graph capable of supporting real-time applications.

The sheer volume of data traversing these Kafka topics is considerable. By way of illustration, Netflix’s applications ingest from multiple distinct Kafka topics, with each topic producing as many as one million messages per second. Records are encoded using the Apache Avro format, and their schemas are maintained within a centralized registry. To achieve a balance between data availability and storage infrastructure expenditures, Netflix customizes retention policies for individual topics, considering factors like throughput and record size. Furthermore, topic records are persisted to Apache Iceberg data warehouse tables, facilitating data backfills when older data expires from Kafka topics. This approach supports efficient capacity planning for data storage.

Apache Flink jobs are responsible for ingesting event records originating from the Kafka streams. Netflix opted for Flink given its robust capabilities in near-real-time event processing. Within Netflix, substantial internal platform support for Flink exists, enabling seamless integration of Flink jobs with Kafka and diverse storage backends.

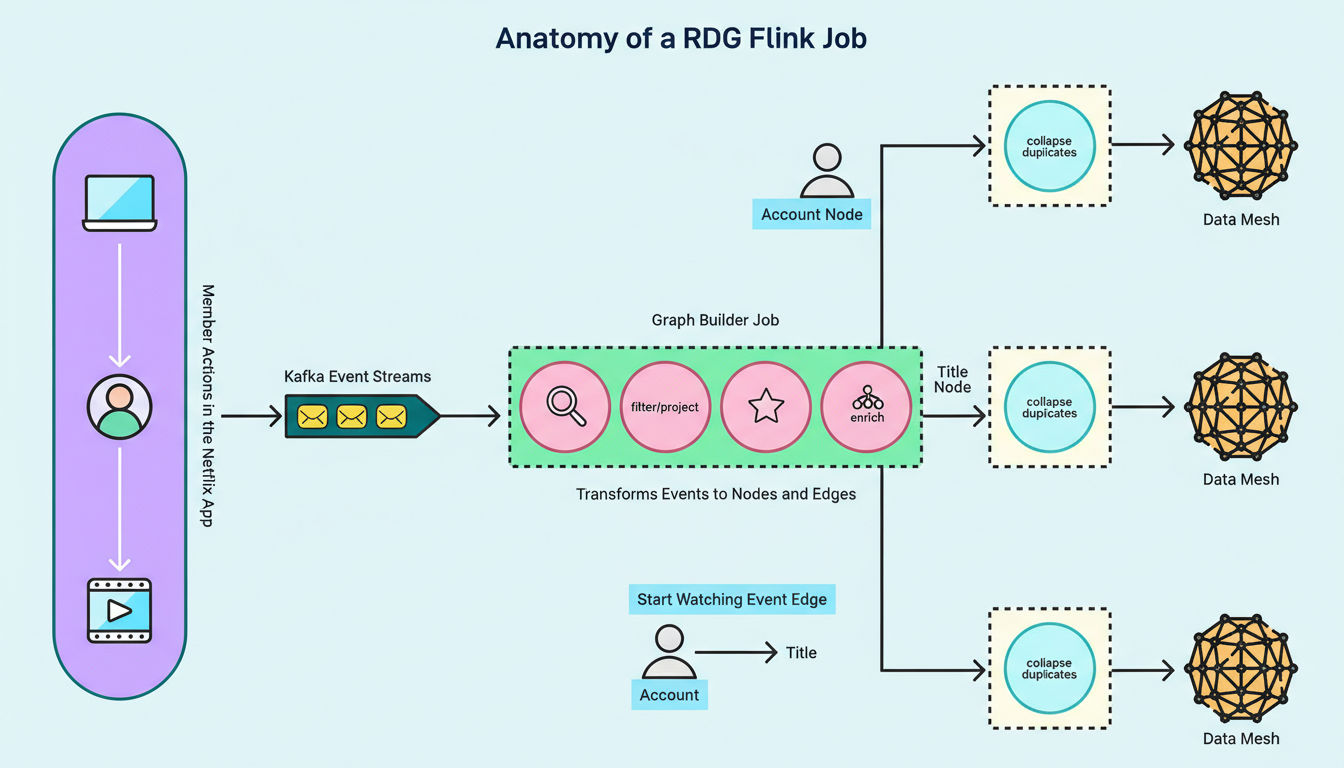

A characteristic Flink job within the RDG pipeline executes a sequence of processing stages:

Initially, the job ingests event records from the upstream Kafka topics.

Subsequently, it applies filtering and projections, eliminating extraneous data based on the presence or absence of specific fields within the events.

Following this, the job enriches events with supplementary metadata, which is stored and retrieved through side inputs.

The job then converts events into fundamental graph primitives, generating nodes that signify entities such as member accounts and show titles, alongside edges that denote relationships or interactions connecting them.

Post-transformation, the job buffers, identifies, and deduplicates concurrent updates targeting identical nodes and edges within a narrow, configurable time window. This crucial stage mitigates the data throughput disseminated downstream and is realized through stateful process functions and timers. Ultimately, the job publishes node and edge records to Data Mesh, an abstraction layer that links data applications with storage systems.

By way of example, Netflix generates in excess of five million total records per second directed towards Data Mesh, which is responsible for persisting these records to data stores accessible by other internal services for querying.

Initially, Netflix implemented a single Flink job to consume all Kafka topics. However, the disparate volumes and throughput patterns across various topics rendered effective tuning impractical. The team subsequently transitioned to a one-to-one mapping between topics and jobs. Although this introduced additional operational overhead, it simplified the maintenance and tuning processes for individual jobs. This evolution in strategy highlights iterative improvements, a core tenet of chaos engineering principles.

In a similar vein, each distinct node and edge type is assigned its own dedicated Kafka topic. While this approach necessitates managing a greater number of topics, Netflix prioritized the capability for independent tuning and scaling of each. The graph data model was intentionally designed for flexibility, ensuring that new node and edge types would be introduced only infrequently.

Subsequent to generating billions of nodes and edges derived from member interactions, Netflix confronted the pivotal inquiry regarding their effective storage methodology.

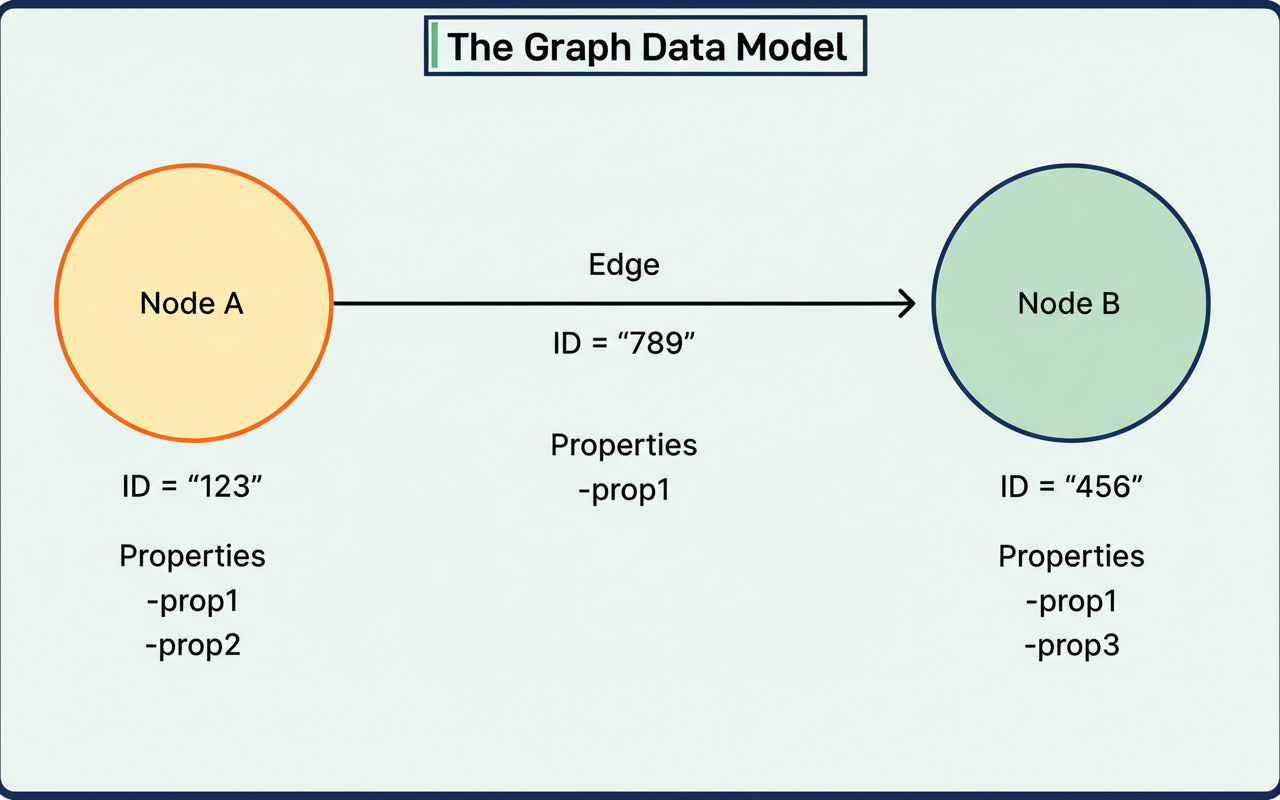

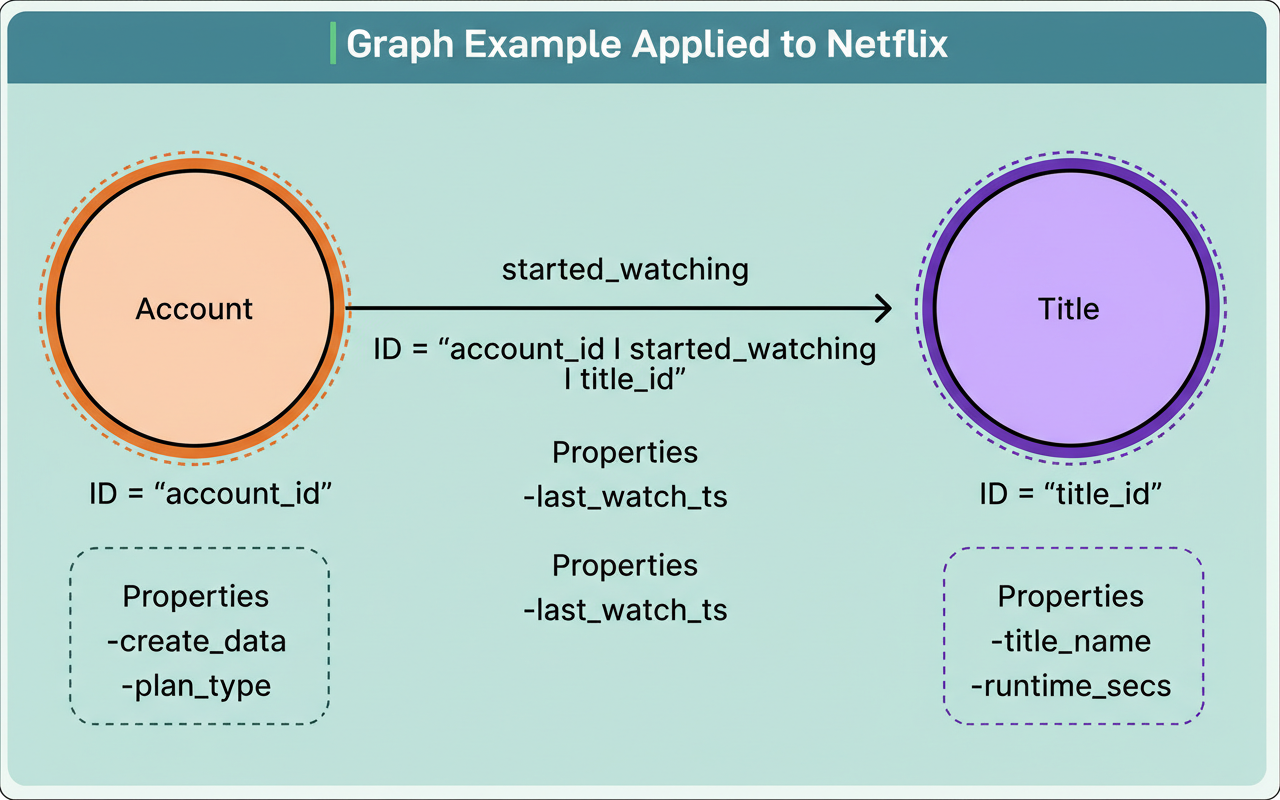

The RDG leverages a property graph model. Nodes within this model symbolize entities such as member accounts, content titles, devices, and games. Each node possesses a distinct identifier and properties that encapsulate supplementary metadata. Edges, conversely, depict relationships between nodes, examples being ‘started watching,’ ‘logged in from,’ or ‘plays.’ Edges likewise feature unique identifiers and properties, including timestamps.

When a member engages with a specific show, the system could generate an account node, replete with properties such as creation date and plan type, a title node detailing elements like title name and runtime, and a ‘started watching’ edge linking these two, complete with properties like the last watch timestamp.

This straightforward abstraction empowers Netflix to effectively represent remarkably intricate member journeys across its entire ecosystem.

The Netflix engineering team conducted an evaluation of conventional graph databases, including Neo4j and AWS Neptune. Although these systems offer extensive capabilities for native graph query support, they presented a combination of scalability, workload, and ecosystem hurdles that rendered them inadequate for Netflix’s specific requirements.

Inherent limitations prevent native graph databases from scaling horizontally effectively for expansive, real-time datasets. Their performance generally deteriorates proportionally with an escalation in node and edge counts or increased query depth.

During preliminary assessments, Neo4j demonstrated adequate performance for datasets containing millions of records; however, it became inefficient when processing hundreds of millions, primarily attributable to elevated memory demands and restricted distributed functionalities.

AWS Neptune exhibits comparable constraints stemming from its single-writer, multiple-reader architecture. This design introduces bottlenecks during the real-time ingestion of substantial data volumes, particularly when operating across Google Cloud multi-region deployments or similar distributed environments.

Furthermore, these systems are not intrinsically engineered for the continuous, high-throughput event streaming workloads deemed essential for Netflix’s operational requirements. They often encounter difficulties with query patterns that entail full dataset scans, property-based filtering, and indexing operations.

Critically, Netflix possesses substantial internal platform support for relational and document databases, a stark contrast to its support for graph databases. Non-graph database systems also present fewer operational complexities for the company. Netflix determined that emulating graph-like relationships within its established data storage systems was a more pragmatic approach than integrating specialized graph infrastructure.

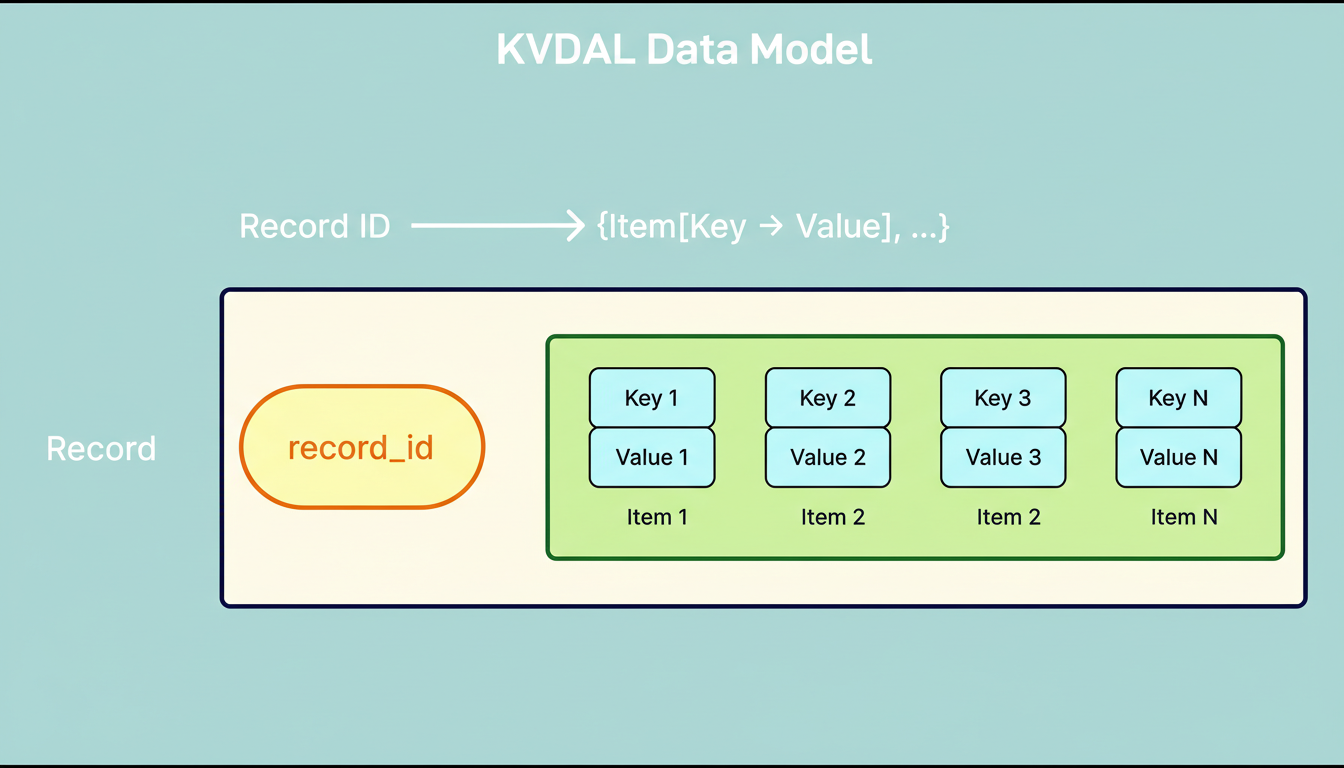

The Netflix engineering team subsequently leveraged KVDAL, the Key-Value Data Abstraction Layer, an integral component of their internal Data Gateway Platform. Constructed upon Apache Cassandra, KVDAL delivers high availability, configurable consistency, and minimal latency, all without necessitating direct management of the underlying storage infrastructure.

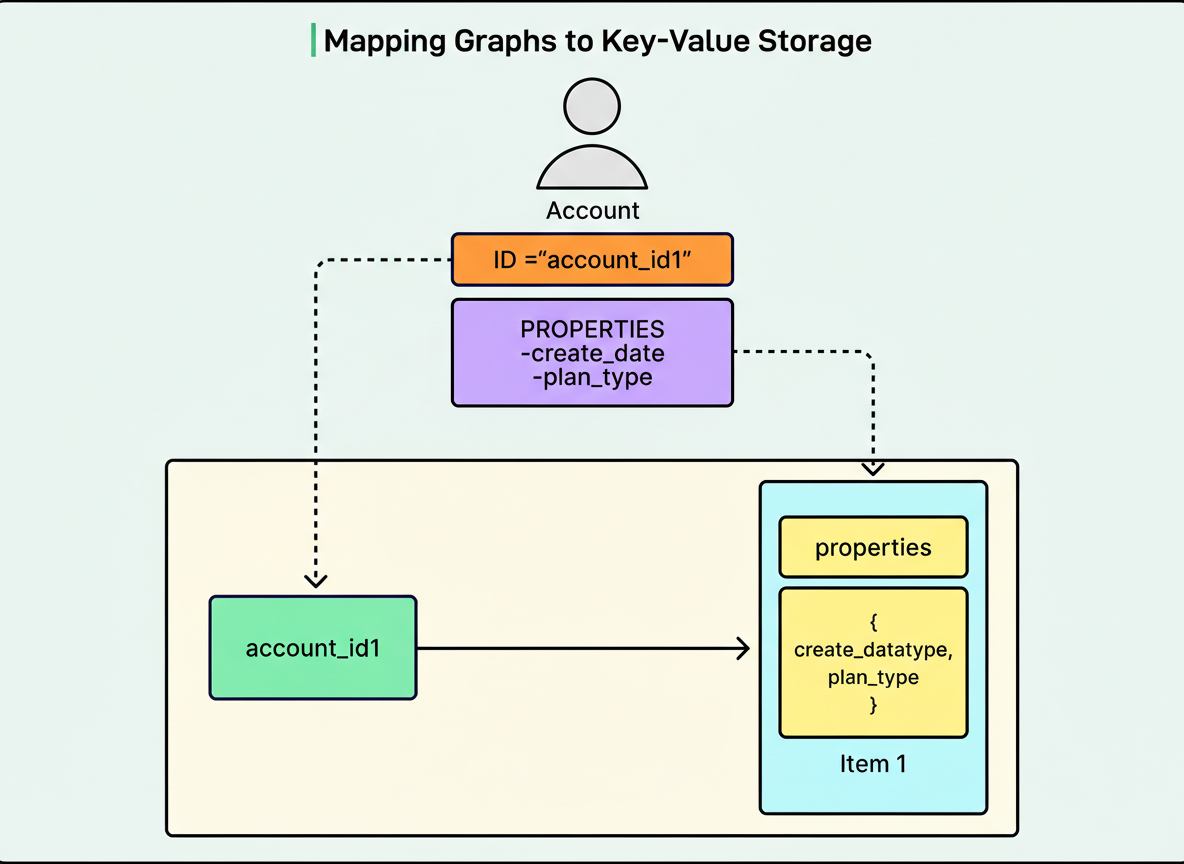

KVDAL employs a two-level map architectural paradigm. Data within this system is structured into records, each uniquely identified by a record ID. Every record encompasses sorted items, where an item constitutes a key-value pair. To interrogate KVDAL, one retrieves a record using its ID and can then optionally filter items based on their respective keys. This mechanism facilitates both highly efficient point lookups and adaptable retrieval of associated data.

In the context of nodes, the unique identifier functions as the record ID, with all associated properties stored as an individual item. For edges, Netflix utilizes adjacency lists. The record ID signifies the origin node, and its items denote all destination nodes to which it connects. Should an account have viewed multiple titles, the corresponding adjacency list would comprise one item per title, complete with properties such as timestamps.

This data format is crucial for facilitating efficient graph traversals. To ascertain all titles a member has watched, Netflix performs a single KVDAL lookup to retrieve the entire relevant record. Additionally, specific titles can be filtered using key filtering, thus avoiding the retrieval of superfluous data.

As Netflix ingests real-time data streams, KVDAL generates new records for newly identified nodes or edges. In instances where an edge exists with an established origin but a novel destination, KVDAL creates a new item within the pertinent existing record. When the identical node or edge is ingested repeatedly, KVDAL overwrites existing values, ensuring that properties such as timestamps remain current. KVDAL additionally offers automated data expiration capabilities on a per-namespace, per-record, or per-item granularity, which affords precise control while simultaneously constraining the expansion of the graph.

Namespaces represent the most potent KVDAL feature utilized by Netflix. Conceptually akin to a database table, a namespace serves as a logical aggregation of records, delineating physical storage characteristics while abstracting underlying system intricacies.

An initial deployment might involve all namespaces supported by a single Cassandra cluster. Should a particular namespace necessitate increased storage or traffic capacity, it can be migrated to its own dedicated cluster for autonomous management. Diverse namespaces possess the flexibility to employ entirely distinct storage technologies. Data requiring low latency, for example, could leverage Cassandra augmented with EVCache caching. Conversely, high-throughput data might be managed by dedicated clusters assigned per namespace. This modularity is crucial for scalable capacity planning and optimized edge network requests per minute.

KVDAL demonstrates the ability to scale to trillions of records per namespace while maintaining single-digit millisecond latencies. Netflix configures a distinct namespace for each node type and edge type. Although this approach might appear expansive, it facilitates independent scaling and fine-tuning, permits flexible storage backends tailored per namespace, and ensures operational isolation, preventing issues in one namespace from affecting others.

Empirical data substantiates the system’s real-world performance. Netflix’s graph currently encompasses over eight billion nodes and exceeds 150 billion edges. The architecture manages approximately two million reads per second and sustains six million writes per second. This operational load is supported by a KVDAL cluster comprising roughly 27 namespaces, underpinned by approximately 12 Cassandra clusters distributed across 2,400 EC2 instances.

These figures do not represent inherent limitations; rather, each component exhibits linear scalability. As the graph expands, Netflix retains the capability to incorporate additional namespaces, clusters, and instances as required.

The RDG architecture implemented by Netflix provides valuable insights.

Occasionally, the optimal solution diverges from the most apparent choice. While Netflix could have adopted purpose-built graph databases, it opted to replicate graph functionalities through key-value storage. This decision was informed by operational practicalities, including internal expertise and established platform support.

Scaling strategies undergo evolution via iterative experimentation. Netflix’s initial monolithic Flink job proved inadequate. It was through practical experience that the team ascertained the superiority of a one-to-one topic-to-job mapping, notwithstanding the increased complexity it introduced.

At massive scale, isolation and independence are paramount. The segregation of each node and edge type into its own namespace facilitated autonomous tuning and diminished the potential impact radius of operational issues.

Constructing solutions upon validated infrastructure yields substantial benefits. Instead of integrating novel systems, Netflix capitalized on battle-tested technologies such as Kafka, Flink, and Cassandra, developing abstractions to fulfill its requirements while capitalizing on their maturity and the company’s operational expertise.

The RDG empowers Netflix to meticulously analyze member interactions across its progressively expanding ecosystem. As the business adapts with new service offerings, this inherently flexible architecture can accommodate changes without necessitating substantial re-architectural efforts.

References:

How and Why Netflix Built a Real-Time Distributed Graph – Part 1

How and Why Netflix Built a Real-Time Distributed Graph – Part 2