OpenAI successfully scaled PostgreSQL to manage millions of queries per second, supporting 800 million ChatGPT users. This achievement was accomplished with a single primary writer, complemented by numerous read replicas.

Initially, such a feat might appear unfeasible. Conventional wisdom often dictates sharding a database beyond a certain scale to prevent system failure. The standard approach typically involves accepting the inherent complexity of distributing data across multiple independent databases.

However, OpenAI’s engineering team pursued an alternative strategy, aiming to explore the maximum capabilities of PostgreSQL.

Over the past year, the database load experienced by OpenAI expanded by over 10X. The team encountered common database-related incidents, including cache layer failures leading to abrupt read spikes, CPU-intensive expensive queries, and write storms resulting from new feature implementations. Nevertheless, through systematic optimization across their entire technology stack, five-nines availability was achieved with low double-digit millisecond latency. This journey, however, presented significant challenges.

This article examines the challenges OpenAI encountered while scaling Postgres and details how the team navigated various complex scenarios.

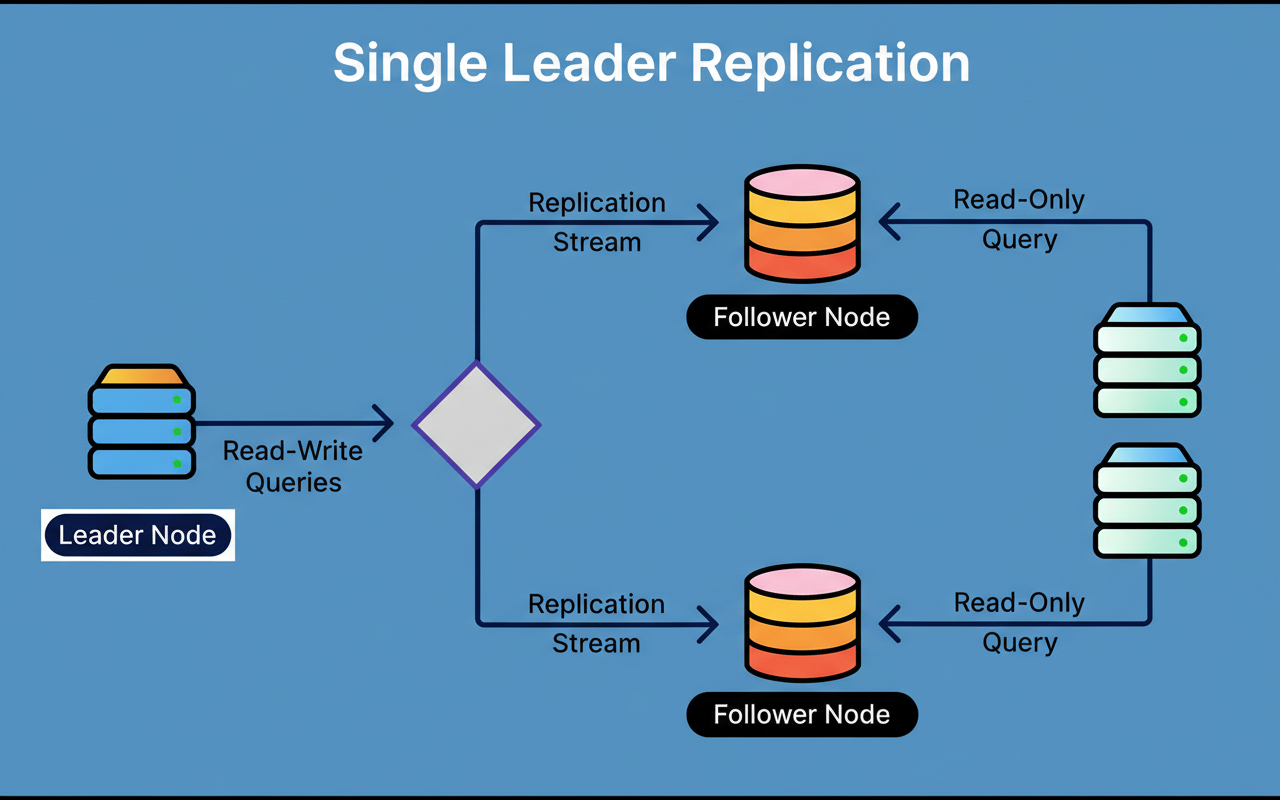

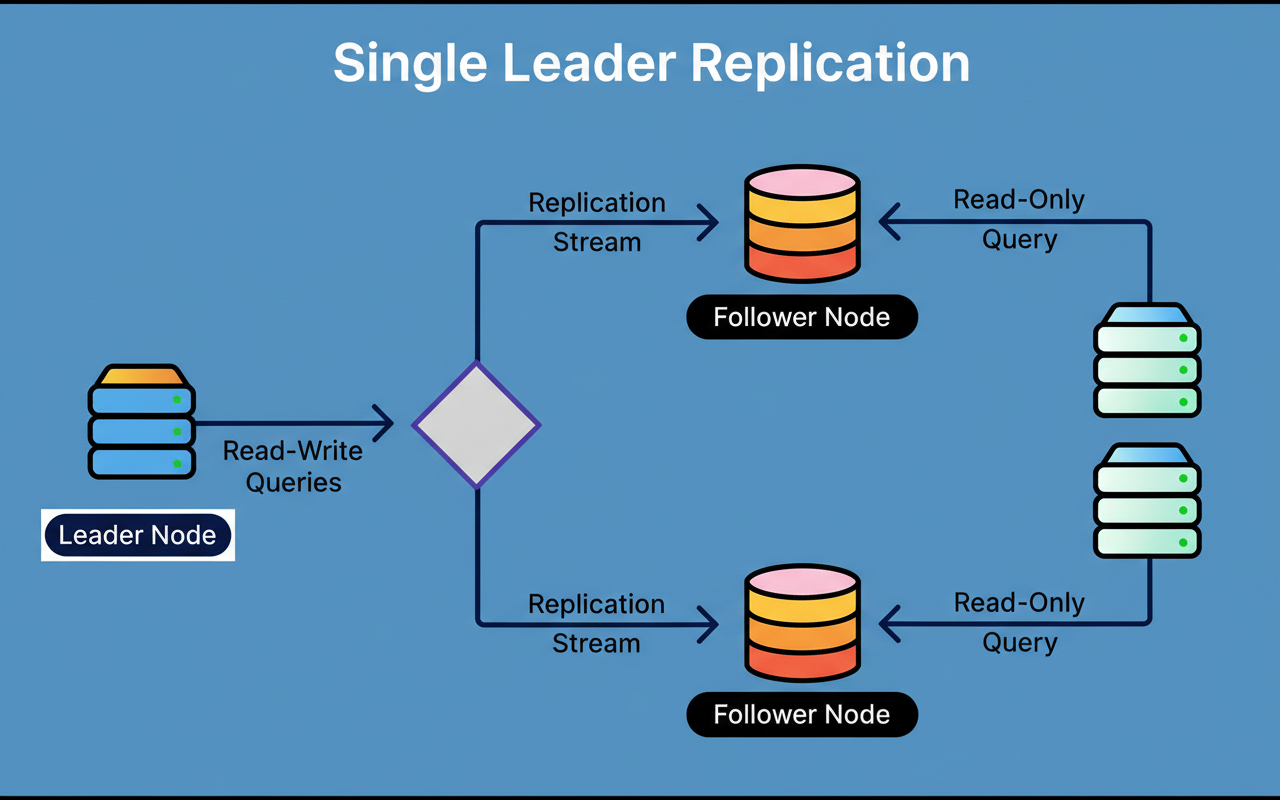

A single-primary architecture designates one database instance to manage all write operations, while multiple read replicas process read queries.

The diagram below illustrates this concept:

This architectural choice inherently introduces a bottleneck, as write operations cannot be distributed. Nevertheless, for workloads characterized by intensive reads, such as ChatGPT, where user interactions predominantly involve data retrieval rather than modification, this architecture can achieve effective scalability with appropriate optimization.

OpenAI opted against sharding its PostgreSQL deployment due to pragmatic considerations. Implementing sharding would necessitate modifications across hundreds of application endpoints, potentially requiring months or even years to complete. Given that its workload is predominantly read-heavy and existing optimizations adequately address current capacity demands, sharding is presently viewed as a future prospect rather than an immediate imperative. This proactive approach to capacity planning ensured stability.

The method by which OpenAI proceeded with scaling its read replicas involved three primary strategic pillars:

The primary database constitutes the most significant bottleneck within the system. OpenAI employed several strategies to alleviate pressure on this singular writer:

OpenAI directs the majority of read queries to replicas instead of the primary database. However, certain read queries must remain on the primary due to their occurrence within write transactions. For these specific queries, the team prioritizes maximum efficiency to prevent sluggish operations that could escalate into widespread system failures.

Workloads amenable to horizontal partitioning were migrated to sharded systems, such as Azure Cosmos DB. These workloads, capable of being split across multiple databases without intricate coordination, demonstrate enhanced scalability. Workloads that present greater challenges for sharding continue to utilize PostgreSQL, though they are undergoing a phased migration.

OpenAI rectified application bugs responsible for superfluous database writes. Where appropriate, lazy writes were implemented to mitigate traffic spikes, thereby preventing abrupt bursts of activity from overwhelming the database. During the backfilling of table fields, stringent rate limits are enforced, even if the process extends beyond a week. This deliberate patience is critical in averting write spikes that might compromise production stability.

Initially, OpenAI identified several expensive queries that consumed a disproportionate amount of CPU resources. One particularly problematic query involved joining 12 tables, and surges in its execution volume triggered multiple high-severity incidents.

The team consequently adopted a practice of avoiding complex multi-table joins within its OLTP system. When joins are indispensable, OpenAI disaggregates complex queries, transferring join logic to the application layer, where it can be distributed across multiple application servers.

Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) frameworks automatically generate SQL from code objects, offering convenience to developers. However, ORMs can sometimes produce inefficient queries. OpenAI rigorously reviews all ORM-generated SQL to ensure optimal performance. Furthermore, timeouts such as idle_in_transaction_session_timeout are configured to prevent prolonged idle queries from obstructing autovacuum, PostgreSQL’s essential cleanup process.

Secondly, Azure PostgreSQL instances are subject to a maximum connection limit of 5,000. OpenAI had previously encountered incidents where connection storms depleted all available connections, resulting in service disruption.

Connection pooling addresses this issue by reusing existing database connections instead of establishing new ones for each request. This method is analogous to carpooling, where individuals share vehicles to alleviate traffic congestion, thereby reducing the burden on database resources.

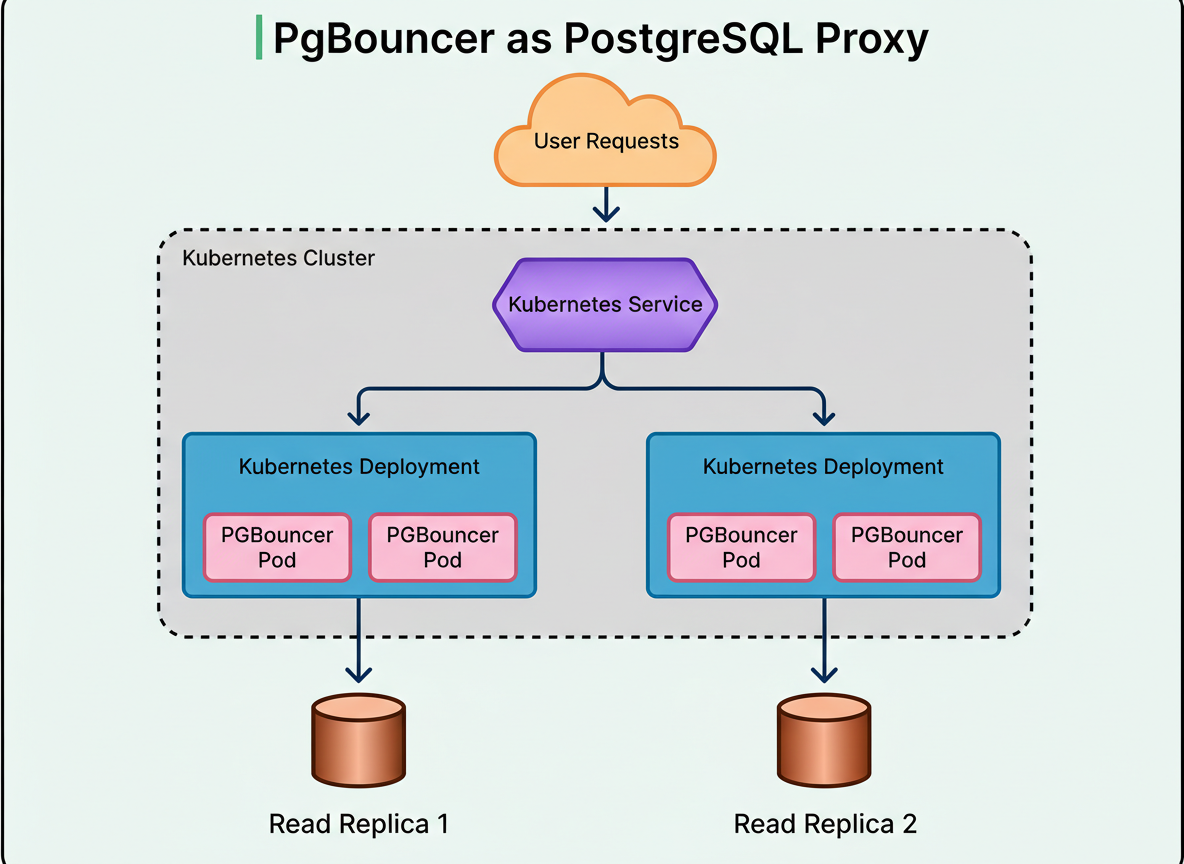

OpenAI implemented PgBouncer as a proxy layer, positioned between applications and databases. PgBouncer operates in either statement or transaction pooling mode, efficiently reusing connections and thereby minimizing the number of active client connections. Benchmarking demonstrated a reduction in average connection time from 50 milliseconds to merely 5 milliseconds.

Each read replica operates its own Kubernetes deployment, hosting multiple PgBouncer pods. Several such deployments are positioned behind a single Kubernetes Service, which orchestrates load balancing across the pods. OpenAI strategically co-locates the proxy, application clients, and database replicas within the same geographic region to mitigate network latency and reduce connection overhead, optimizing edge network requests per minute.

The diagram below illustrates this setup:

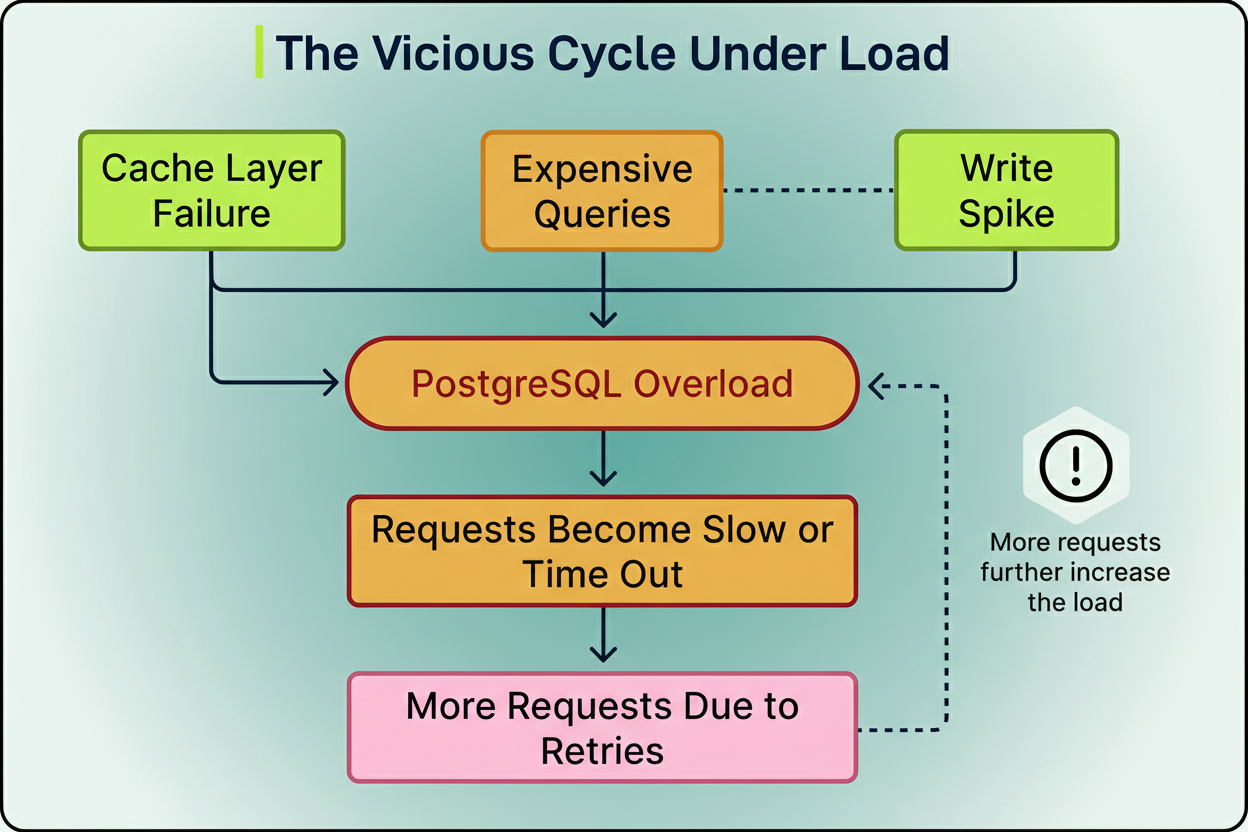

OpenAI identified a recurring pattern in incidents. To reduce read pressure on PostgreSQL, a caching layer is utilized to serve the majority of read traffic.

However, an unexpected decline in cache hit rates can lead to a surge of cache misses, directing massive request volumes straight to PostgreSQL. This means an upstream issue can cause an abrupt spike in database load, potentially due to widespread cache misses from a caching layer failure, CPU saturation from expensive multi-way joins, or a write storm initiated by a new feature launch.

As resource utilization escalates, query latency increases, and requests begin to time out. Subsequently, applications initiate retries for failed requests, further intensifying the load. This establishes a feedback loop that can severely degrade the entire service.

To counteract this scenario, the OpenAI engineering team implemented a cache locking and leasing mechanism. When multiple requests encounter a miss for the same cache key, only one request is granted a lock and proceeds to fetch data from PostgreSQL to repopulate the cache. All other requests then await this cache update, rather than concurrently accessing the database.

The diagram below illustrates this mechanism:

Further preventive measures include OpenAI’s implementation of rate limiting across the application, connection pooler, proxy, and query layers. This measure effectively prevents sudden traffic spikes from overwhelming database instances and initiating cascading failures. The team also avoids excessively short retry intervals, which possess the potential to trigger retry storms where failed requests multiply exponentially.

The ORM layer was enhanced to incorporate rate limiting capabilities, allowing for the complete blocking of specific query patterns when necessary. This targeted approach to load shedding facilitates rapid recovery from sudden surges of resource-intensive queries.

Despite these extensive efforts, OpenAI encountered situations where particular requests consumed disproportionate resources on PostgreSQL instances, leading to what is known as the noisy neighbor effect. For example, the launch of a new feature might introduce inefficient queries that heavily consume CPU, thereby impeding the performance of other critical features.

To mitigate this, OpenAI implements workload isolation onto dedicated instances. Requests are categorized into low-priority and high-priority tiers and subsequently routed to separate database instances. This segregation ensures that spikes in low-priority workloads do not adversely affect the performance of high-priority requests. The same strategic approach is applied uniformly across various products and services.

PostgreSQL employs Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) to manage concurrent transactions. When a query modifies a tuple (database row) or even a single field, PostgreSQL generates a new version by copying the entire row. This architectural choice enables multiple transactions to access different versions concurrently without mutual obstruction.

Nevertheless, MVCC introduces challenges, particularly for write-heavy workloads. It results in write amplification, as modifying a single field necessitates writing an entire row. Furthermore, it contributes to read amplification, requiring queries to scan multiple tuple versions, termed dead tuples, to retrieve the most current version. This phenomenon leads to table bloat, index bloat, increased overhead for index maintenance, and complex requirements for autovacuum tuning.

OpenAI’s primary approach to mitigating MVCC limitations involves migrating write-heavy workloads to alternative systems and optimizing applications to minimize superfluous writes. The team also restricts schema changes to lightweight operations that do not instigate full table rewrites.

Another architectural constraint associated with PostgreSQL pertains to schema changes. Even minor schema modifications, such as altering a column type, can provoke a full table rewrite within PostgreSQL. During such a rewrite, PostgreSQL constructs a new copy of the entire table with the applied change. For large tables, this process can extend for hours and impede access.

To address this, OpenAI enforces rigorous rules concerning schema changes:

In a single primary database configuration, the failure of that instance can impact the entire service. OpenAI addressed this critical risk through the implementation of multiple strategic approaches.

Firstly, the majority of critical read-only requests were offloaded from the primary to replicas. Should the primary fail, read operations would continue to function. While write operations would cease, the overall service impact is substantially mitigated.

Secondly, OpenAI operates the primary database in High Availability mode, supported by a hot standby. A hot standby is a continuously synchronized replica maintained in a state of immediate readiness to assume primary responsibilities. In the event of primary failure or required maintenance, OpenAI can rapidly promote the standby, thereby minimizing downtime. The Azure PostgreSQL team has dedicated significant effort to ensure these failovers remain secure and dependable, even under conditions of high load.

For scenarios involving read replica failures, OpenAI deploys multiple replicas within each region, ensuring sufficient capacity headroom. The failure of a single replica does not precipitate a regional outage, as traffic is automatically rerouted to other available replicas.

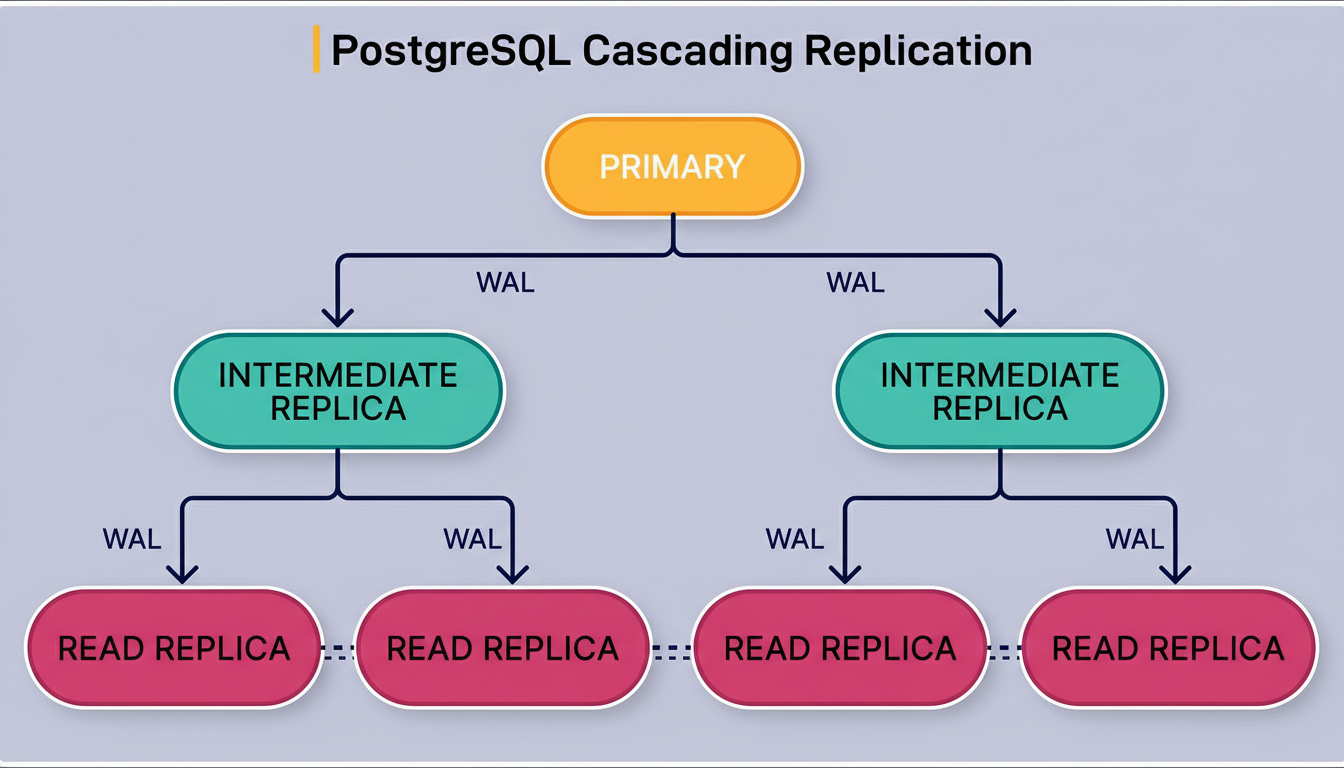

The primary database streams Write Ahead Log (WAL) data to every read replica. WAL comprises a comprehensive record of all database changes, which replicas replay to maintain synchronization. As the number of replicas grows, the primary is tasked with delivering WAL to an increasing number of instances, escalating pressure on network bandwidth and CPU resources. This inevitably leads to higher and more inconsistent replica lag.

As previously indicated, OpenAI currently manages nearly 50 read replicas distributed across multiple geographic regions. While this configuration scales effectively with large instance types and high network bandwidth, the team acknowledges that replicas cannot be added indefinitely without eventually overwhelming the primary.

To address this prospective limitation, OpenAI is engaged in a collaborative effort with the Azure PostgreSQL team to develop cascading replication. Within this architecture, intermediate replicas serve to relay WAL to downstream replicas, rather than the primary streaming directly to every replica. This hierarchical structure facilitates scaling to potentially over 100 replicas without overburdening the primary. However, it introduces additional operational complexity, particularly concerning failover management. The feature remains under testing until the team can guarantee its safe and reliable failover capabilities.

The diagram below illustrates this architecture:

OpenAI’s comprehensive optimization efforts have yielded impressive results.

The system is capable of handling millions of queries per second while sustaining near-zero replication lag. The architecture consistently achieves low double-digit millisecond p99 latency, indicating that 99 percent of requests are completed within approximately 50 milliseconds. Furthermore, the system demonstrates five-nines availability, which translates to 99.999 percent uptime.

Over the past 12 months, OpenAI reported only a single SEV-0 PostgreSQL incident. This occurrence coincided with the viral launch of ChatGPT ImageGen, during which write traffic experienced an abrupt surge of over 10x as more than 100 million new users registered within a single week.

Moving forward, OpenAI remains committed to migrating its remaining write-heavy workloads to sharded systems. The team is actively collaborating with Azure to facilitate cascading replication, enabling the safe scaling to a significantly larger number of read replicas. Continued exploration of additional approaches, including sharded PostgreSQL or other distributed systems, will be pursued as infrastructure demands evolve.

OpenAI’s experience demonstrates that PostgreSQL can reliably support substantially larger read-heavy workloads than commonly perceived. However, attaining this level of scale necessitates rigorous optimization, meticulous monitoring, and stringent operational discipline. The team’s success stems not from the adoption of the newest distributed database technology but from a profound understanding of their workload characteristics and the systematic elimination of bottlenecks.