When Stripe initially launched, the company gained recognition for its ability to integrate payment processing into any business with merely seven lines of code.

This represented a significant accomplishment. Transforming the intricate process of credit card handling into a straightforward code snippet was perceived as revolutionary. Essentially, a developer could execute a basic curl command in a terminal and promptly observe a successful credit card payment.

Nevertheless, constructing and sustaining a payment API capable of operating across numerous countries, each with distinct payment methods, banking systems, and regulatory demands, presents one of the most formidable challenges. Often, companies either limit themselves to supporting only a few payment methods or compel developers to craft varied integration code for each specific market.

Stripe necessitated multiple API evolutions over the subsequent decade to accommodate credit cards, bank transfers, Bitcoin wallets, and cash payments via a unified integration.

Achieving this evolution proved complex. This article examines the progression of Stripe’s payment APIs throughout the years, the technical hurdles encountered, and the engineering choices that have defined modern payment processing.

Upon Stripe’s debut in 2011, credit cards largely defined the US payment ecosystem. The initial API architecture mirrored this prevalent reality.

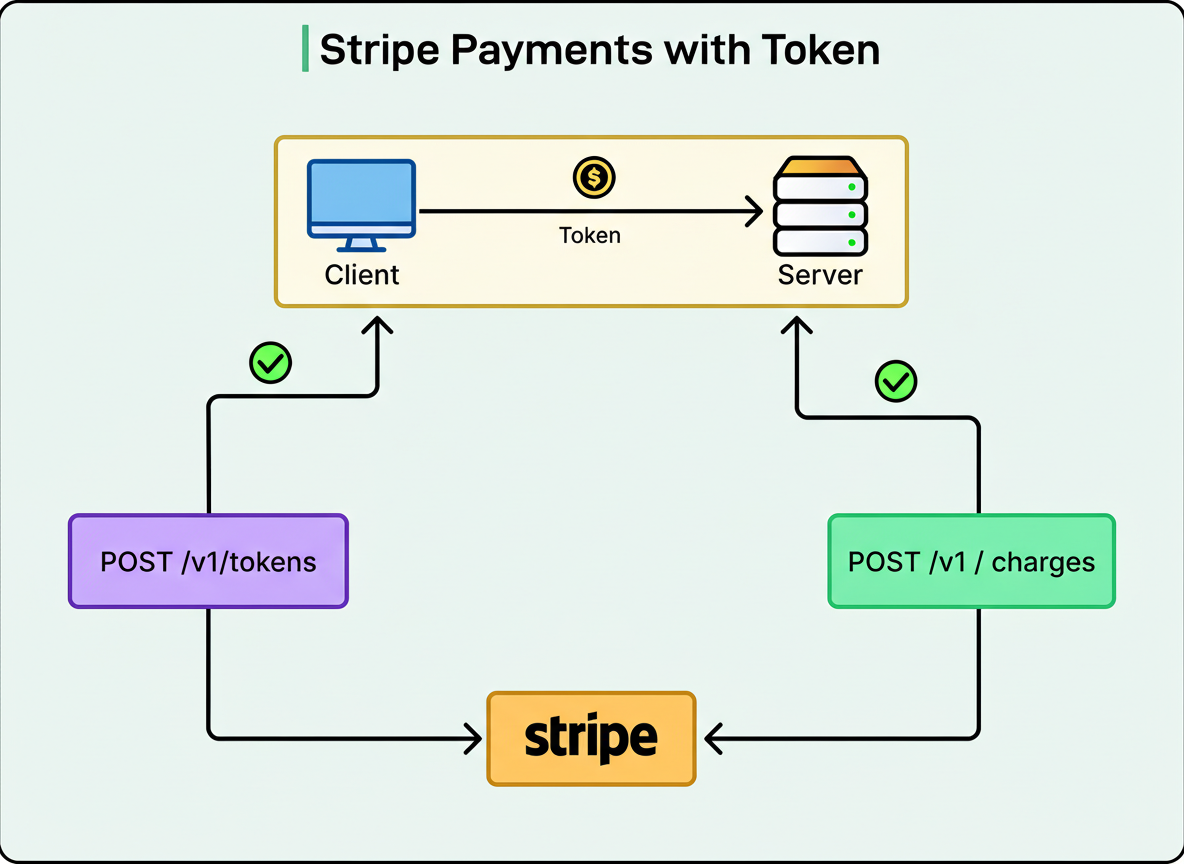

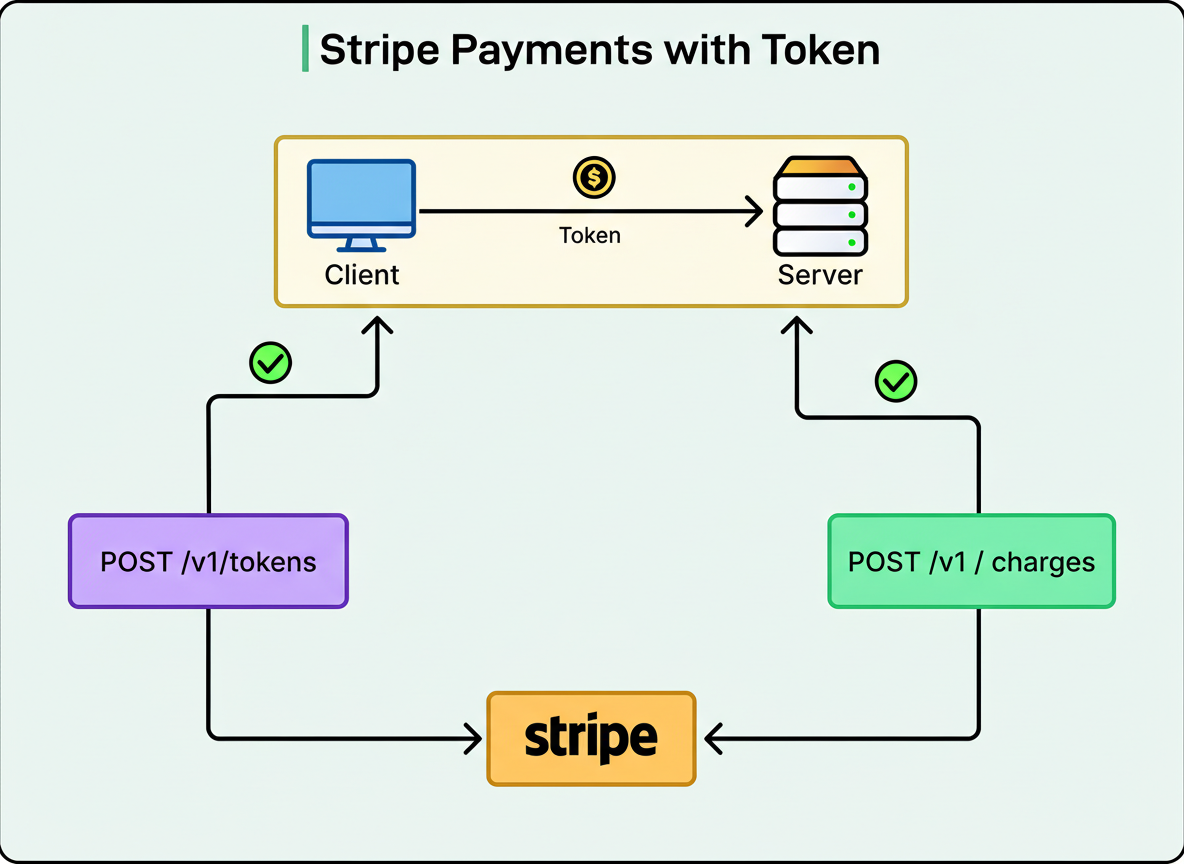

Stripe introduced two foundational concepts destined to underpin its platform.

The first concept was the Token. When a customer inputted their card details into a web browser, this information was transmitted directly to Stripe’s servers via a JavaScript library known as Stripe.js.

This methodology was vital for security. By preventing card data from residing on merchant servers, Stripe assisted businesses in circumventing intricate PCI compliance mandates. PCI compliance denotes the security protocols businesses must adhere to when handling credit card data, which are costly and technically demanding to implement correctly.

In exchange for the card details, Stripe issued a Token. A Token functioned as a secure reference to the card information, with the actual card number securely stored within Stripe’s systems. The Token served merely as a pointer to this protected data.

The second concept introduced was the Charge. Subsequent to receiving a Token from the client, a merchant’s server could generate a Charge utilizing that Token and a secret API key.

A Charge encapsulated the actual payment request. When a Charge was created, the payment either concluded successfully or failed instantly. This immediate feedback mechanism is termed synchronous processing, signifying an instantaneous outcome.

The diagram below illustrates this approach:

The payment processing flow adhered to a typical pattern observed in conventional web applications:

With Stripe’s expansion, the necessity arose to accommodate payment methods other than credit cards. In 2015, ACH debit and Bitcoin were incorporated. These payment methods presented fundamental distinctions that posed challenges to the prevailing API architecture.

Payment methods exhibit variations across two crucial dimensions.

Firstly, the timing of payment finalization is key. Finalization implies certainty that funds are guaranteed, allowing goods to be dispatched to the customer. Credit card payments finalize instantly. In contrast, Bitcoin payments can require approximately an hour, while ACH debit payments might necessitate several days for finalization.

Secondly, the initiator of the payment varies. For credit cards and ACH debit, the merchant initiates the payment by charging the customer. With Bitcoin, the customer generates a transaction and dispatches it to the merchant, thereby requiring customer action prior to any monetary transfer.

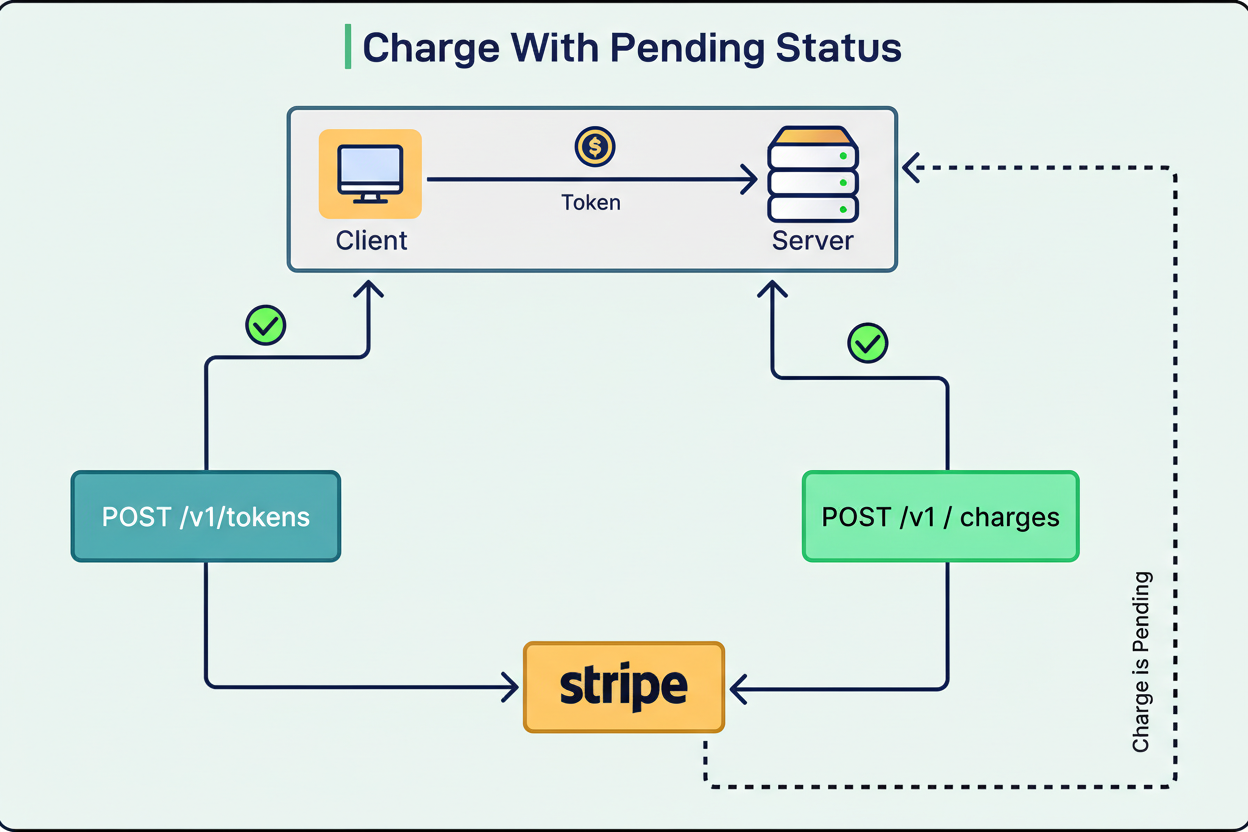

For ACH debit, Stripe expanded the Token resource to encompass both card details and bank account details. However, it became necessary to incorporate a pending state into the Charge. An ACH debit Charge would commence as pending and only transition to a successful state days later. Merchants were required to implement webhooks to ascertain when the payment had actually completed.

The diagram below illustrates this:

For contextual understanding, a webhook functions as a mechanism through which Stripe notifies a server when an event occurs. Rather than a server continually querying Stripe for payment status, Stripe dispatches a notification to a specified URL on the server when the status changes. The server must configure an endpoint to listen for and process these incoming notifications.

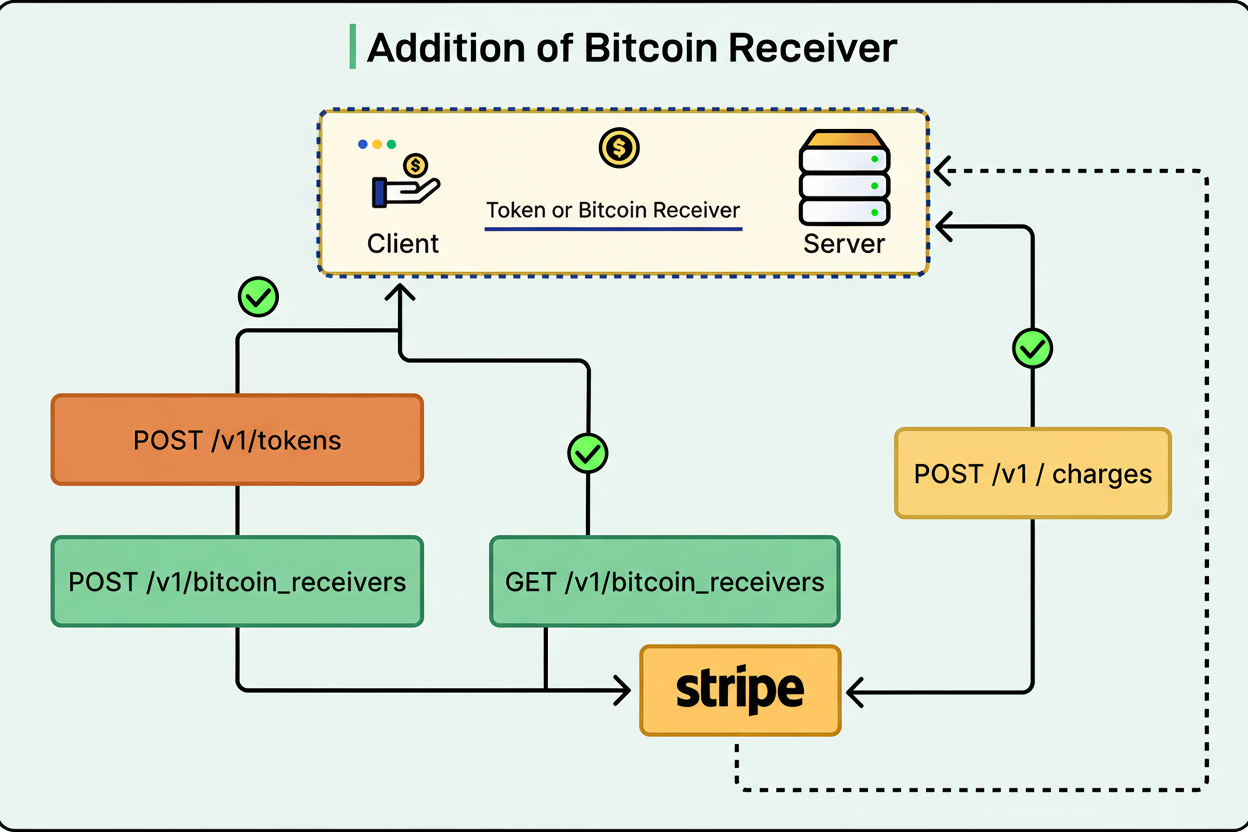

For Bitcoin, the existing abstractions proved entirely inadequate. Stripe consequently introduced a novel BitcoinReceiver resource, which served as temporary storage for funds. This resource featured a straightforward state machine characterized by a single boolean property named ‘filled’. A state machine is defined as a system capable of existing in various states and transitioning between them based on specific events. The BitcoinReceiver could be either ‘filled’ (true) or ‘not filled’ (false).

The Bitcoin payment flow operated as follows:

The diagram below depicts this process:

This evolution introduced a layer of complexity. Merchants were now tasked with managing two distinct state machines to finalize a single payment: the BitcoinReceiver on the client side and the Charge on the server side. Furthermore, handling asynchronous payment finalization necessitated the use of webhooks.

Over the subsequent two years, Stripe incorporated numerous additional payment methods. Most exhibited similarities to Bitcoin, necessitating customer action for payment initiation. The Stripe engineering team recognized that developing a novel receiver-like resource for each payment method would become unmanageable. Consequently, they resolved to design a unified payments API.

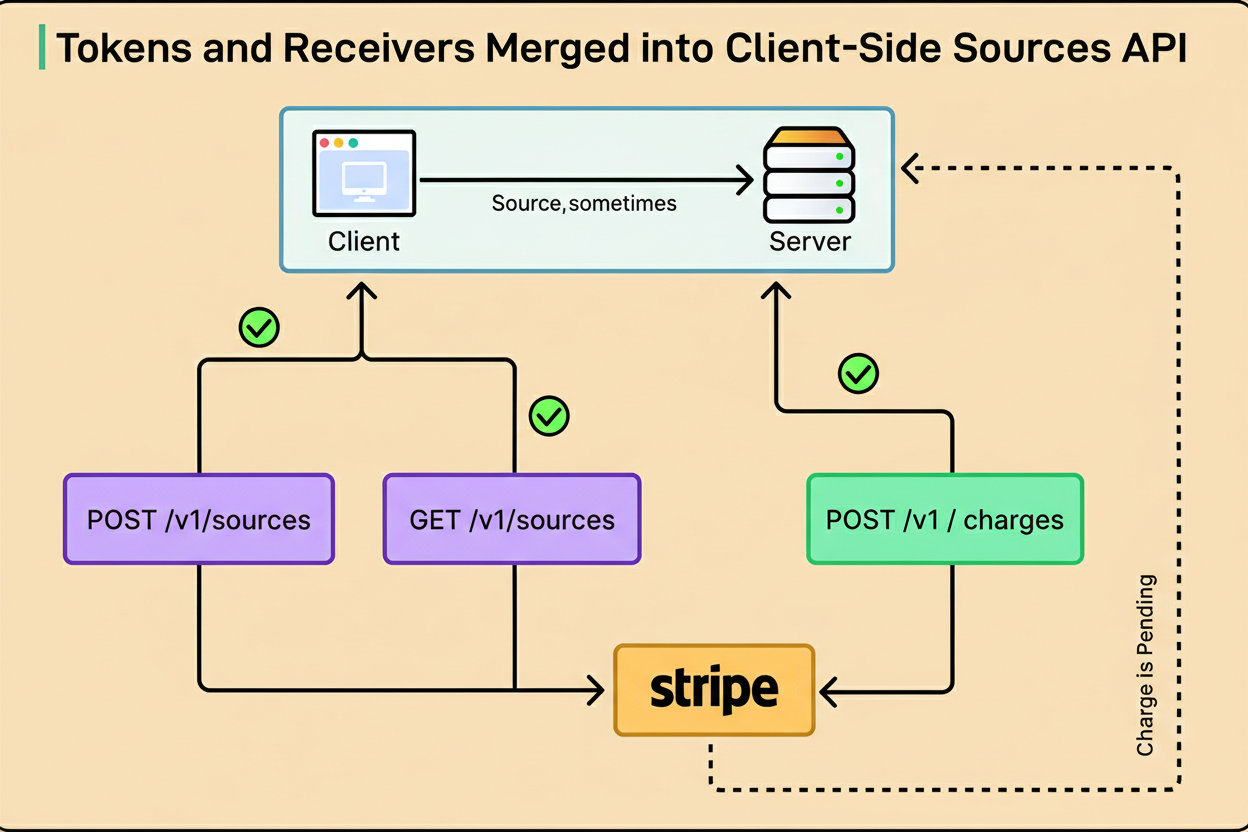

To accomplish this, Stripe consolidated Tokens and BitcoinReceivers into a singular client-driven state machine designated as a Source. Upon creation, a Source could be either immediately chargeable, akin to credit cards, or pending, similar to payment methods requiring customer intervention. The server-side integration maintained its simplicity: creating a Charge utilizing the Source.

The diagram below illustrates this:

The Sources API supported various payment options, including cards, ACH debit, SEPA direct debit, iDEAL, Alipay, Giropay, Bancontact, WeChat Pay, Bitcoin, and many others. All these payment methods leveraged the same two API abstractions: a Source and a Charge.

Although this approach initially appeared elegant, the team encountered significant issues once the integration flow within real-world applications was thoroughly understood. Consider a prevalent scenario involving iDEAL, the dominant payment method in the Netherlands:

To mitigate this risk, Stripe advised merchants to either poll the API from their server until the Source achieved a chargeable state or to listen for the source.chargeable webhook event to initiate the Charge. However, if a merchant’s application experienced temporary downtime, these webhooks would not be delivered, preventing the server from creating the Charge.

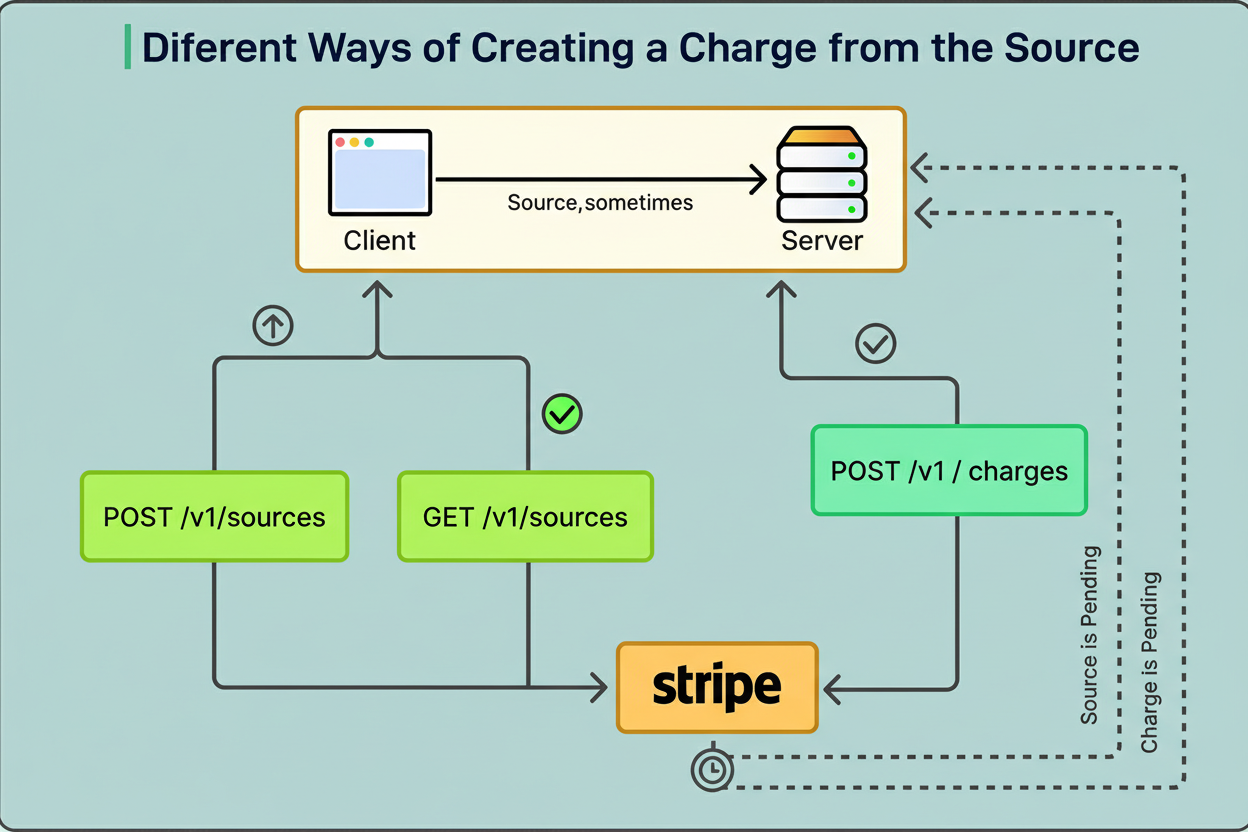

The integration complexity escalated due to the varied behavior of different Sources:

The diagram below illustrates this point:

Stripe recognized that its system had been architected predominantly around the most straightforward payment method: credit cards. Upon reviewing all available payment methods, cards were, in fact, the anomaly. Credit cards stood as the sole payment method that finalized instantaneously and demanded no customer action for payment initiation. All other methods presented greater complexity.

Developers were consequently obliged to comprehend the success, failure, and pending states of two distinct state machines, whose states diverged significantly across various payment methods. This necessitated a substantially greater conceptual grasp than initially implied by the promise of seven lines of code.

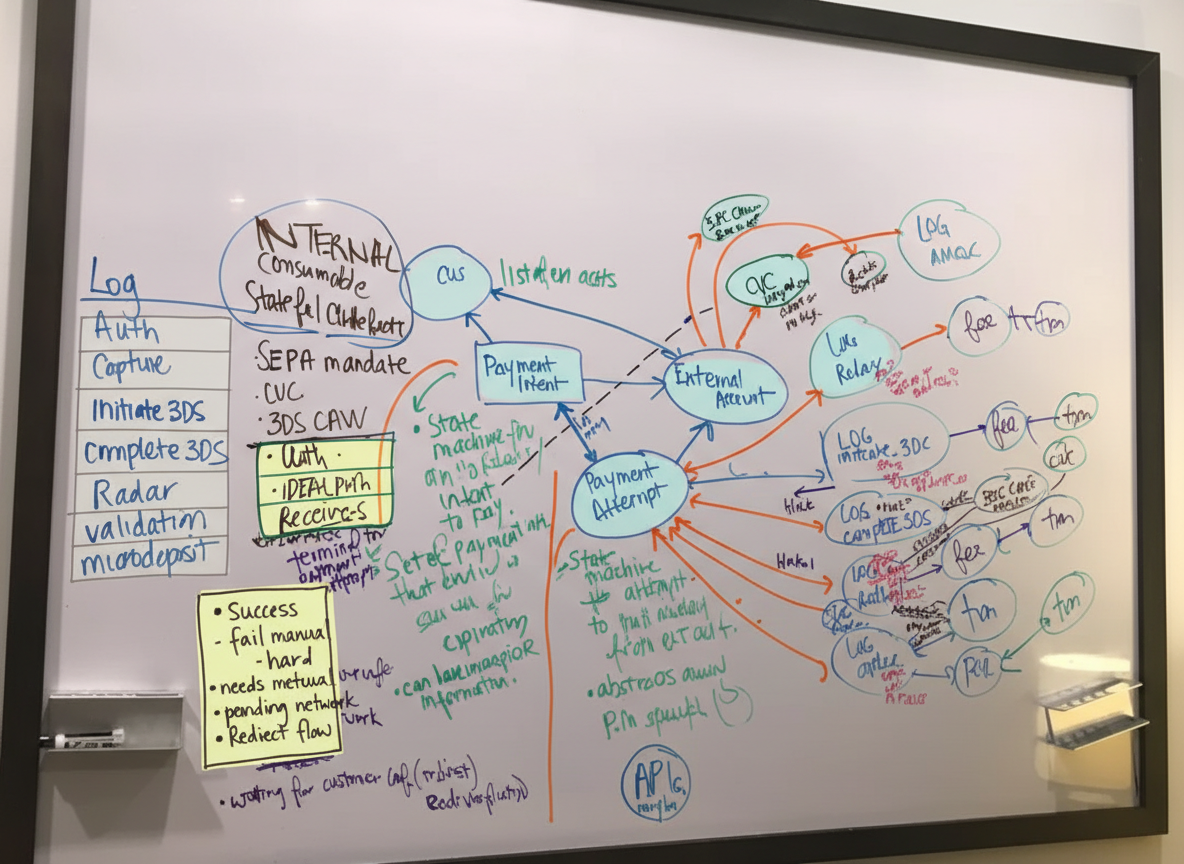

In late 2017, Stripe convened a compact team comprising four engineers and one product manager. This group secluded themselves in a conference room for three months, dedicated to the sole objective of architecting a genuinely unified payments API capable of supporting all global payment methods.

The team adhered to stringent guidelines:

Source: Stripe Engineering Blog

Source: Stripe Engineering Blog

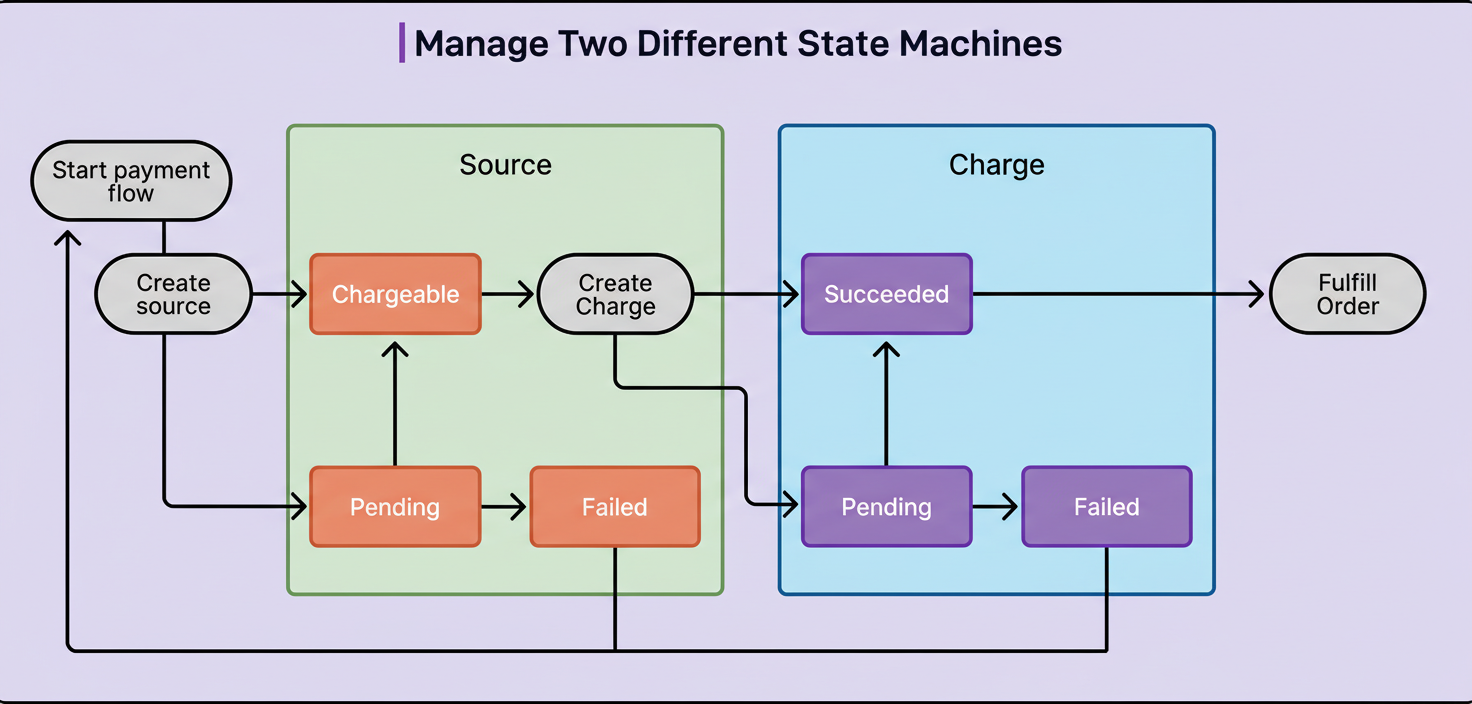

The team developed two novel concepts that ultimately delivered genuine unification.

A PaymentMethod signifies the “how of a payment.” It encompasses static information regarding the payment instrument the customer intends to employ. This includes the payment scheme and necessary credentials for monetary transfer, such as card details, bank account particulars, or customer email. For certain methods, like Alipay, only the payment method’s designation is required, as the method itself manages the collection of further information. Significantly, a PaymentMethod lacks a state machine and holds no transaction-specific data; it functions merely as a description of how a payment is to be processed.

A PaymentIntent embodies the “what of a payment.” It captures transaction-specific data, including the amount to be charged and the currency. The PaymentIntent serves as the stateful object that monitors a customer’s payment attempt. Should one payment attempt be unsuccessful, the customer has the option to retry with an alternative PaymentMethod. The same PaymentIntent can be utilized with multiple PaymentMethods until the payment successfully processes.

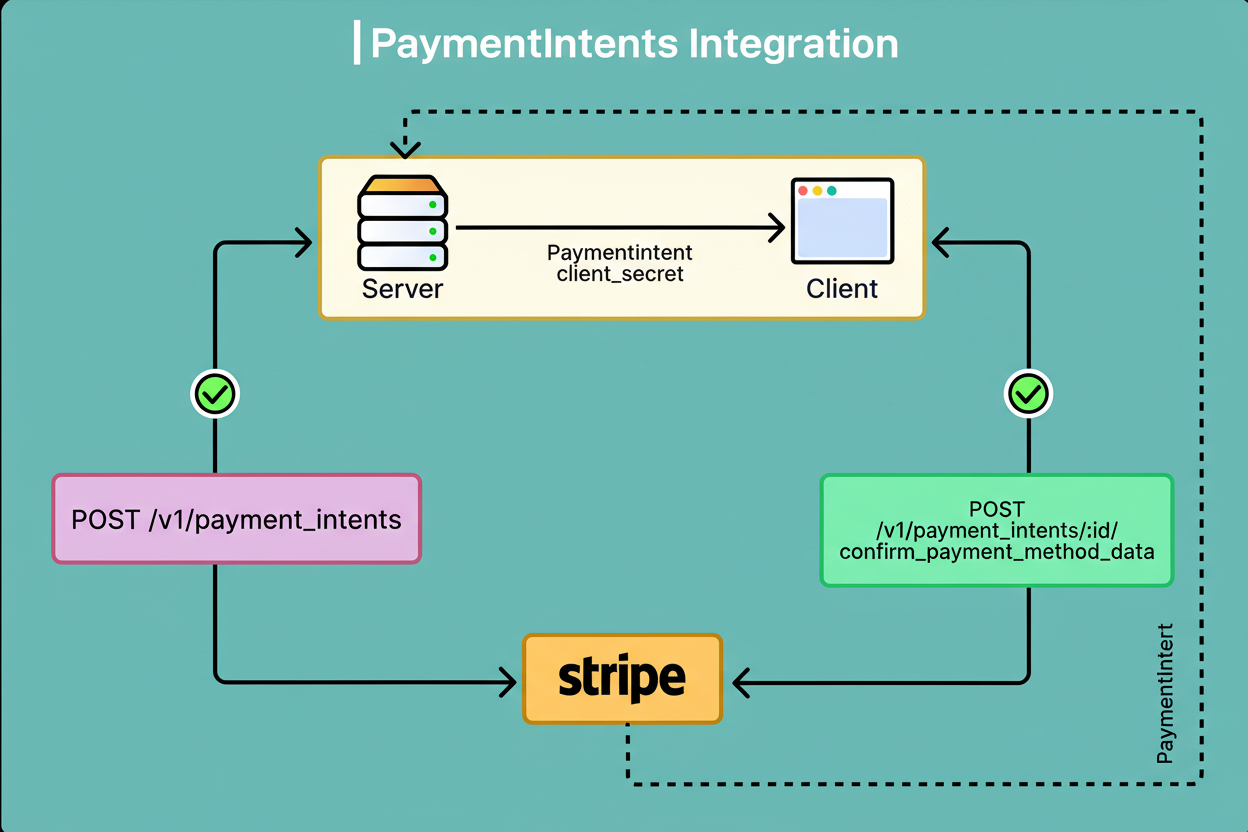

The diagram below illustrates this:

The pivotal realization involved establishing a single, predictable state machine applicable to all payment methods:

requires_payment_method: Indicates the necessity to specify the customer’s payment approach.requires_confirmation: Denotes that the payment method is prepared for payment initiation.requires_action: Signifies that the customer must undertake an action, such as authentication or redirection.processing: Represents Stripe’s ongoing processing of the payment.succeeded: Confirms that funds are guaranteed, allowing the merchant to fulfill the order.Remarkably, a explicit failed state is absent. If a payment attempt proves unsuccessful, the PaymentIntent reverts to requires_payment_method, enabling the customer to attempt payment again using an alternative method.

The updated integration operates uniformly across all payment methods:

client_secret to the browser.requires_action state, accompanied by specific instructions.payment_intent.succeeded webhook.This methodology brought substantial enhancements compared to previous Sources and Charges. Only a single webhook handler was required, and it did not reside in the critical path for monetary collection. The entire workflow leveraged a unified, predictable state machine. The integration exhibited resilience against client disconnections due as the PaymentIntent maintained persistence on the server. Most significantly, this identical integration functioned across all payment methods with minimal parameter adjustments.

While the design of the PaymentIntents API represented a demanding yet gratifying endeavor, its launch consumed nearly two years, primarily due to a perception obstacle: the new API no longer evoked the simplicity of merely seven lines of code.

In the process of standardizing the API across all payment methods, the integration of card payments became more intricate. The revised flow inverted the sequence of client and server requests and introduced webhook events that had previously been optional. For developers constructing conventional web applications focused solely on accepting card payments in the US and Canada, PaymentIntents presented an objectively more complex integration than the earlier Charges API.

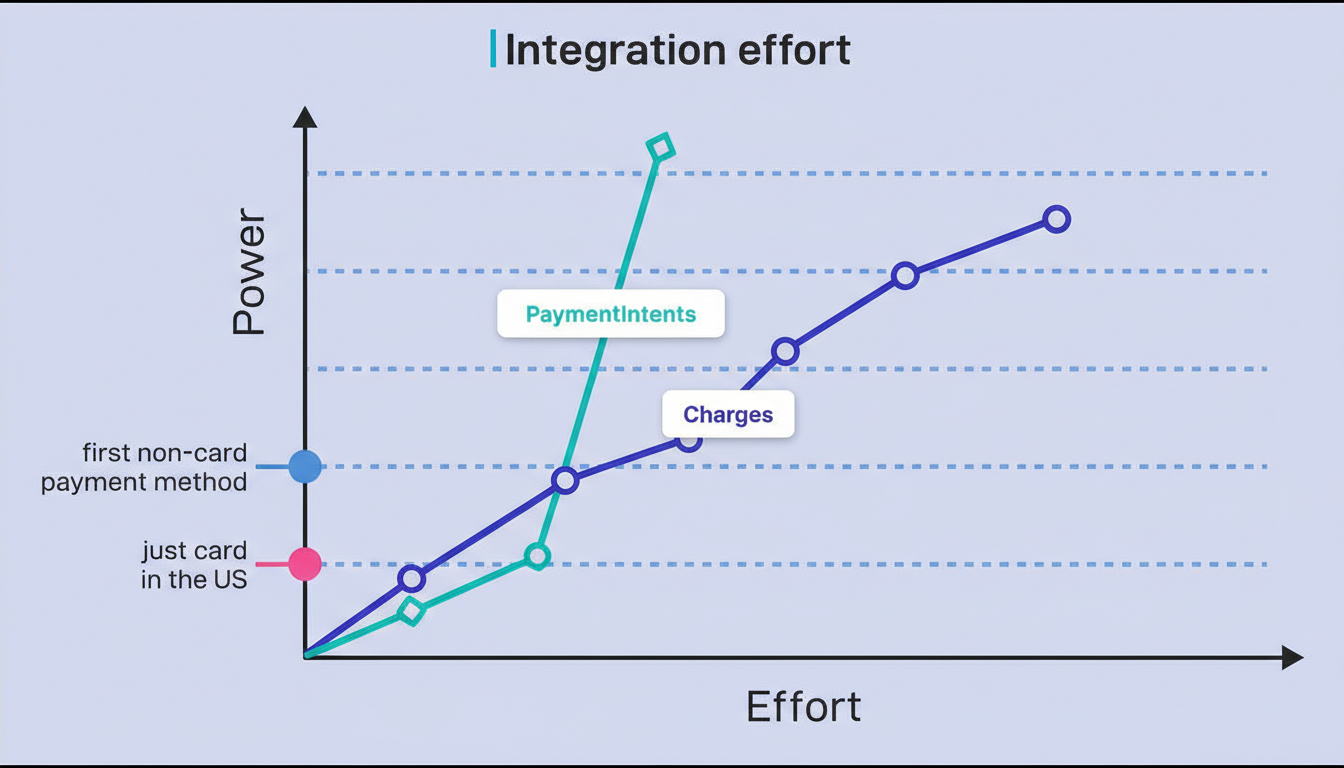

The power-to-effort curve exhibited a different characteristic. Each incremental payment method could be added to a PaymentIntents integration with minimal cost. However, commencing with only card payments necessitated a greater initial investment of effort. Speed is a critical factor for startups aiming for rapid deployment. With the Charges API, establishing card payments was intuitive and low-effort.

Source: Stripe Engineering Blog

Source: Stripe Engineering Blog

Stripe’s resolution involved introducing convenient API packaging designed to accommodate developers seeking the most straightforward possible workflow. The default integration was termed the global payments integration, and a simplified variant, known as card payments without bank authentication, was developed.

This streamlined integration employed a specific parameter called error_on_requires_action. This parameter instructs the PaymentIntent to return an error if any customer action is mandated to finalize the payment. A merchant utilizing this parameter is unable to address actions required by the PaymentIntent state machine, effectively causing it to emulate the behavior of the legacy Charges API.

The parameter’s nomenclature clearly communicates the merchant’s choice. When the necessity arises to handle actions or incorporate new payment methods, the appropriate course of action becomes evident: remove this parameter and begin managing the requires_action state. Developers leveraging this packaging are not compelled to alter the core resources even when transitioning to the comprehensive global integration.

Stripe underscored that an exceptional API transcends the API itself. Several approaches employed by the company include:

The team also undertook the less glamorous but crucial task of updating all documentation, support articles, and pre-written responses that referenced older APIs. Outreach was extended to community content creators, requesting updates to their materials. Numerous tutorials were produced for both external users and internal support personnel.

The trajectory from Charges to PaymentIntents illuminated crucial principles pertaining to API design.

Firstly, successful products often accrue product debt over time, akin to technical debt. For API products, addressing this debt is particularly challenging, as developers cannot be compelled to fundamentally restructure their existing integrations. Adding parameters to current requests proves considerably simpler than introducing entirely new abstractions.

Secondly, designing from first principles is indispensable. Stripe discerned that Charges and Tokens served as foundational elements not because they represented the optimal abstraction for global payments, but simply because they constituted the initial APIs developed. The team was therefore compelled to disregard existing APIs and approach the problem with a fresh perspective.

Thirdly, maintaining simplicity does not equate to merely reducing the count of resources or parameters. Two excessively burdened abstractions do not offer greater simplicity than four distinctly defined abstractions. Simplicity, in this context, implies ensuring APIs are consistent and predictable, concurrently with establishing appropriate packaging.

Fourthly, migration necessitates compromise. Stripe generated Charge objects in the background for each PaymentIntent to preserve compatibility with legacy integrations. This facilitated merchants in transitioning their payment workflow without disrupting their analytics and reporting infrastructure.

Finally, API design is inherently a collaborative endeavor. The pivotal breakthrough emerged when engineers and product managers engaged in intensive cooperation, setting aside individual devices to concentrate entirely on comprehending the problem domain.

In summary, Stripe’s progression from an initial seven lines of code to a highly sophisticated global payments API unequivocally demonstrates that simplicity and robust functionality are not conflicting objectives. The core challenge lies in constructing abstractions that proficiently manage internal complexities while concurrently presenting a predictable and consistent interface to developers.

References: