When individuals interact with modern large language models (LLMs) such as GPT, Claude, or Gemini, they observe a process fundamentally distinct from how humans formulate sentences. While humans naturally construct thoughts and convert them into words, LLMs operate through a cyclical conversion process. Understanding this process reveals both the capabilities and limitations of these powerful systems, offering insights valuable for capacity planning in their deployment.

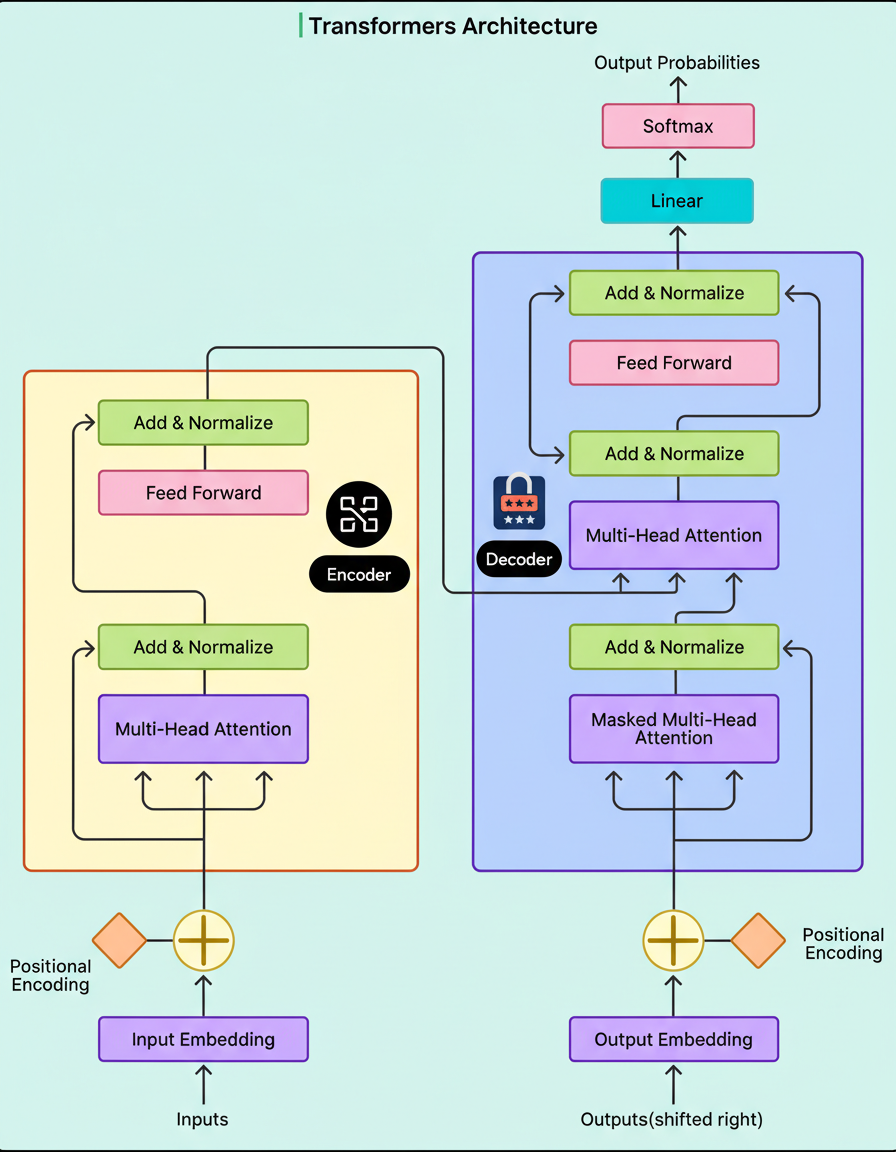

At the core of most contemporary LLMs resides an architecture known as a transformer. Introduced in 2017, transformers are sequence prediction algorithms constructed from neural network layers. The architecture comprises three essential components:

A diagram illustrating this process is provided below:

Transformers process all words concurrently rather than sequentially, which allows them to learn from extensive text datasets and capture complex relationships between words. This article will examine the transformer architecture’s operation in a step-by-step manner, a critical foundation for understanding performance implications and resilience, much like practicing chaos engineering principles in distributed systems.

Before any computation can occur, the model must convert text into a workable format. This process begins with tokenization, where text is broken down into fundamental units called tokens. These units are not always complete words; they can be subwords, word fragments, or even individual characters.

Consider the example input: “I love transformers!” The tokenizer might break this into: [”I”, “ love”, “ transform”, “ers”, “!”]. It is notable that “transformers” became two separate tokens. Each unique token within the vocabulary is assigned a unique integer ID:

These IDs are arbitrary identifiers lacking inherent relationships. Tokens 150 and 151 are not similar merely because their numerical values are close. The overall vocabulary typically encompasses 50,000 to 100,000 unique tokens that the model acquired during its training phase.

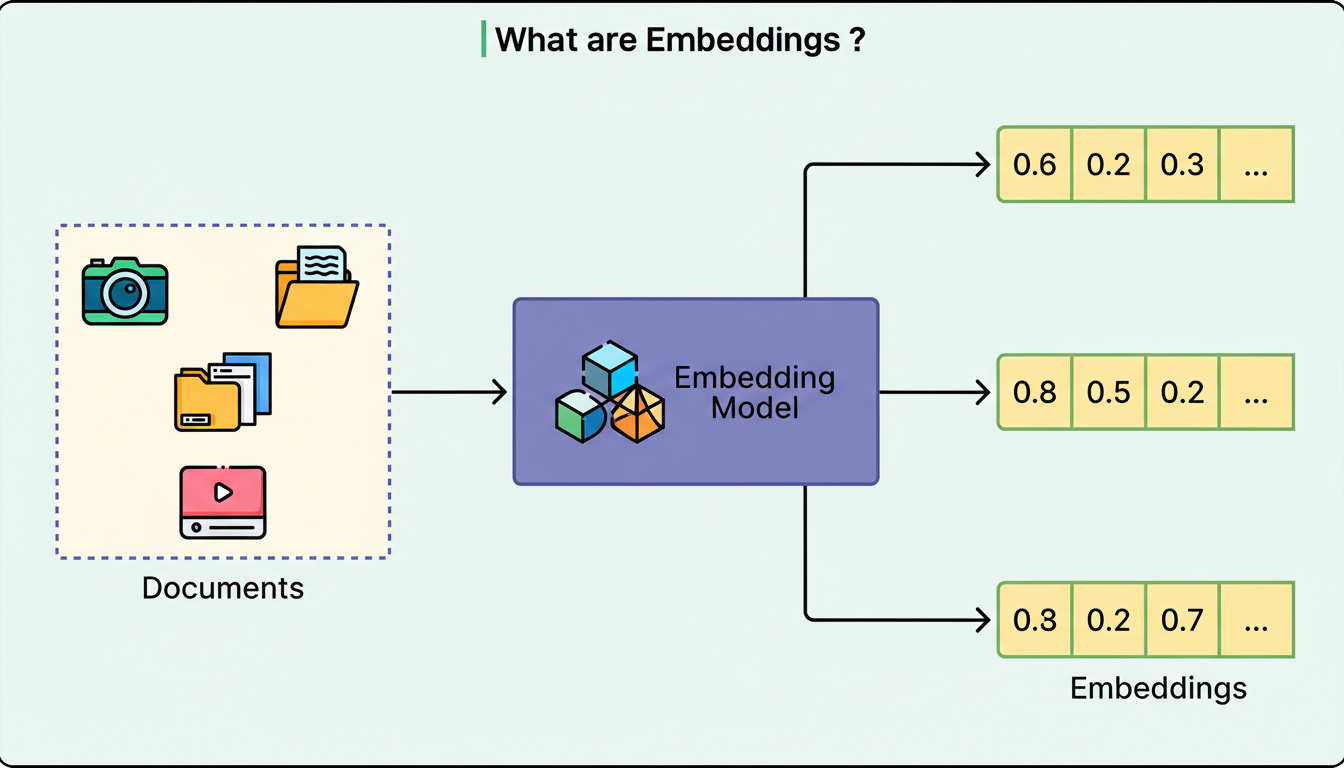

Neural networks cannot directly process token IDs, as these are merely fixed identifiers. Each token ID is mapped to a vector, which is a list of continuous numbers typically containing hundreds or thousands of dimensions. These are referred to as embeddings.

Here is a simplified example illustrating five dimensions (real models may utilize 768 to 4096):

It can be observed that “dog” and “wolf” exhibit similar numerical values, whereas “car” is distinctly different. This creates a semantic space where related concepts tend to cluster together.

The necessity for multiple dimensions arises because with only one number per word, contradictions might occur. For example:

In this scenario, “rare” and “debt” both possess similar negative values, implying a relationship that is nonsensical. Hundreds of dimensions enable the model to represent complex relationships without such contradictions. Within this semantic space, mathematical operations can be performed. For instance, the embedding for “king” minus “man” plus “woman” approximately yields the embedding for “queen.” These relationships emerge during training from patterns observed in text data.

Transformers inherently lack an understanding of word order. Without additional information, sentences such as “The dog chased the cat” and “The cat chased the dog” would appear identical because both contain the same tokens.

The solution involves positional embeddings. Every position is mapped to a position vector, analogous to how tokens are mapped to meaning vectors.

For the token “dog” appearing at position 2, the representation might appear as follows:

This combined embedding captures both the meaning of the word and its contextual usage. This integrated representation is then fed into the transformer layers.

The transformer layers implement the attention mechanism, which constitutes the key innovation behind these models’ remarkable power. Each transformer layer operates using three components for every token: queries, keys, and values. This can be conceptualized as a fuzzy dictionary lookup where the model compares its target (the query) against all available answers (the keys) and returns weighted combinations of the corresponding values.

Consider a concrete example with the sentence: “The cat sat on the mat because it was comfortable.”

When the model processes the word “it,” it must determine what “it” refers to. The sequence of events is as follows:

First, the embedding for “it” generates a query vector, essentially asking, “To what noun am I referring?”

Next, this query is compared against the keys from all previous tokens. Each comparison produces a similarity score. For example:

The raw scores are subsequently converted into attention weights that sum to 1.0. For example:

Finally, the model utilizes the value vectors from each token and combines them using these calculated weights. For example, the value from “cat” contributes 75 percent to the output, “mat” contributes 20 percent, and all other elements are nearly disregarded. This weighted combination becomes the new representation for “it,” encapsulating the contextual understanding that “it” most likely refers to “cat.”

This attention process occurs in every transformer layer, with each layer learning to detect distinct patterns.

Early layers acquire basic patterns such as grammar and common word pairs. When processing “cat,” these layers might heavily attend to “The” because they learn the relationship between articles and their nouns.

Middle layers discern sentence structure and relationships between phrases. They might identify that “cat” is the subject of “sat” and that “on the mat” forms a prepositional phrase indicating location.

Deep layers extract more abstract meaning. They might comprehend that this sentence describes a physical situation and implies the cat is comfortable or resting.

Each layer progressively refines the representation. The output of one layer serves as the input for the next, with each successive layer adding more contextual understanding.

Importantly, only the final transformer layer is responsible for predicting an actual token. All intermediate layers perform the same attention operations but merely transform the representations to be more useful for subsequent layers. A middle layer does not output token predictions; instead, it outputs refined vector representations that flow to the next layer.

This stacking of numerous layers, each specializing in different aspects of language understanding, is what enables LLMs to capture complex patterns and generate coherent text.

After traversing all layers, the final vector must be converted back into text. The unembedding layer compares this vector against every token embedding and produces scores.

For example, to complete “I love to eat,” the unembedding process might yield:

These arbitrary scores are then converted into probabilities using softmax:

Tokens with similar scores (65.2 versus 64.8) receive similar probabilities (28.3 versus 24.1 percent), while low-scoring tokens result in near-zero probabilities.

The model does not simply select the highest probability token. Instead, it randomly samples from this distribution. This can be visualized as a roulette wheel where each token is allocated a slice proportional to its probability. Pizza receives 28.3 percent, tacos receive 24.1 percent, and 42 receives a microscopic slice.

The rationale for this randomness is that consistently selecting a specific value, such as “pizza,” would lead to repetitive, unnatural output. Random sampling weighted by probability allows for the selection of “tacos,” “sushi,” or “barbeque,” thereby producing varied and natural responses. Occasionally, a lower-probability token is selected, contributing to more creative outputs.

The generation process reiterates for every token. Consider an example where the initial prompt is “The capital of France.” Here’s how different cycles proceed through the transformer:

Cycle 1:

Cycle 2:

Cycle 3:

Cycle 4:

Final output: “The capital of France is Paris.”

The [EoS] or end-of-sequence token signals completion. Each cycle processes all previous tokens. This explains why generation can slow down as responses lengthen.

This mechanism is termed autoregressive generation because each output is dependent on all previous outputs. If an unusual token is selected (perhaps “chalk” with 0.01 percent probability in “I love to eat chalk”), all subsequent tokens will be influenced by this choice.

The transformer flow operates in two distinct contexts: training and inference.

During training, the model acquires language patterns from billions of text examples. It commences with random weights and gradually adjusts them. The training process unfolds as follows:

Training text: “The cat sat on the mat.”

The model receives: “The cat sat on the”

With random initial weights, the model might predict:

The training process calculates the error (the probability for “mat” should have been higher) and utilizes backpropagation to adjust every weight:

Each adjustment is minute (e.g., from 0.245 to 0.247), but it accumulates across billions of examples. After encountering “sat on the” followed by “mat” thousands of times in various contexts, the model learns this pattern. Training typically spans weeks on thousands of GPUs and entails costs amounting to millions of dollars. Once completed, the weights are frozen.

During inference, the transformer operates with its frozen weights:

User query: “Complete this: The cat sat on the”

The model processes the input with its learned weights and outputs: “mat” (85 percent), “floor” (8 percent), “chair” (3 percent). It samples “mat” and returns it. No weight changes occur.

The model leverages its learned knowledge but does not acquire any new information. Conversations do not update model weights. To impart new information to the model, it would necessitate retraining with new data, a process requiring substantial computational resources.

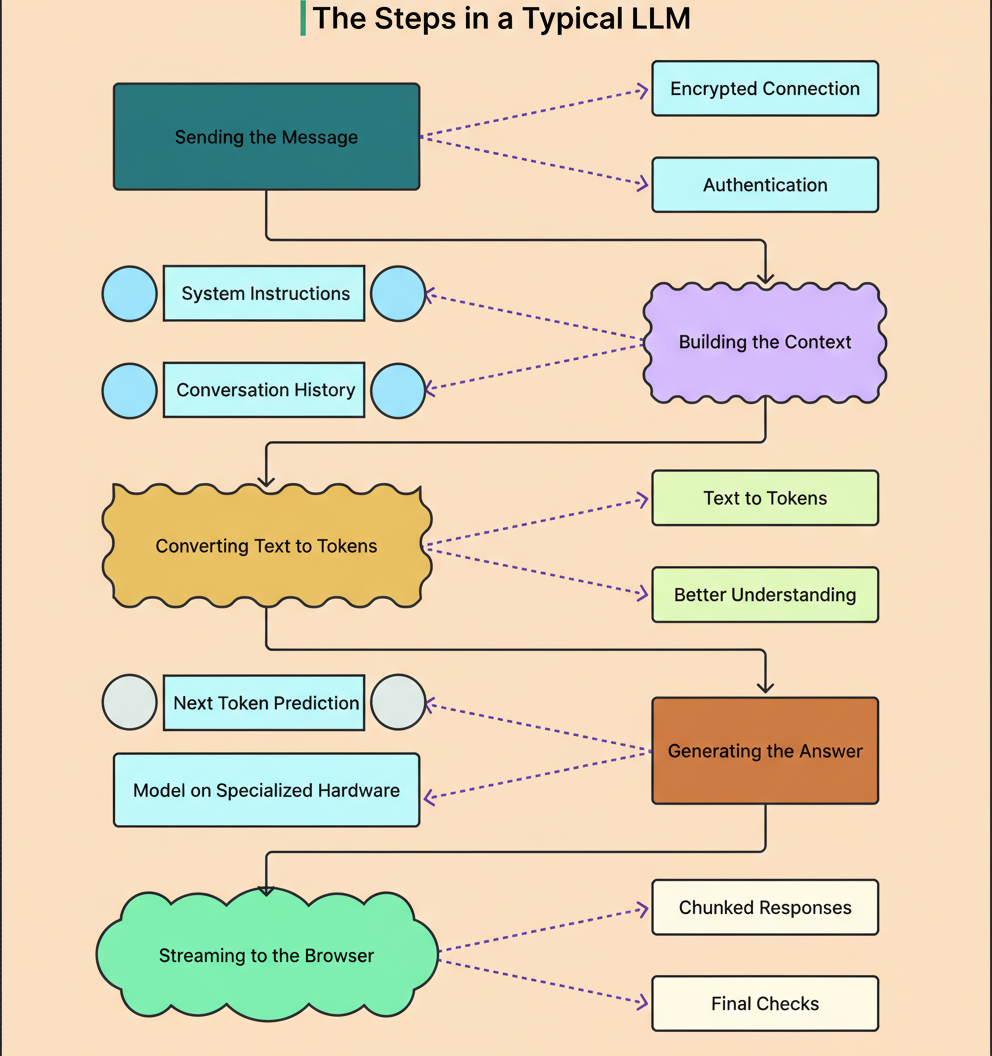

A diagram below illustrates the various steps in an LLM execution flow:

The transformer architecture offers an elegant solution for understanding and generating human language. By converting text to numerical representations, employing attention mechanisms to capture relationships between words, and stacking numerous layers to learn increasingly abstract patterns, transformers empower modern LLMs to produce coherent and useful text.

This process encompasses seven key steps that repeat for every generated token: tokenization, embedding creation, positional encoding, processing through transformer layers with attention mechanisms, unembedding to scores, sampling from probabilities, and decoding back to text. Each step builds upon the preceding one, transforming raw text into mathematical representations that the model can manipulate, and then back into human-readable output.

Understanding this process reveals both the capabilities and limitations of these systems. Essentially, LLMs are sophisticated pattern-matching machines that predict the most likely next token based on patterns learned from massive datasets, enabling their use in diverse applications from Black Friday Cyber Monday scale testing insights to edge network requests per minute optimization strategies in real-world deployments.